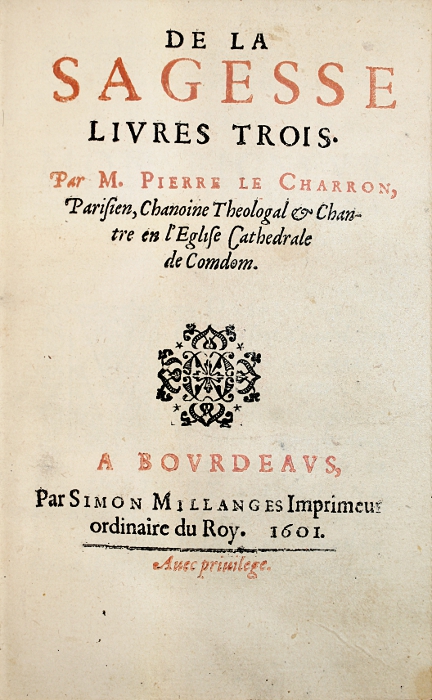

Bourdêus, Simon Millanges, 1601.

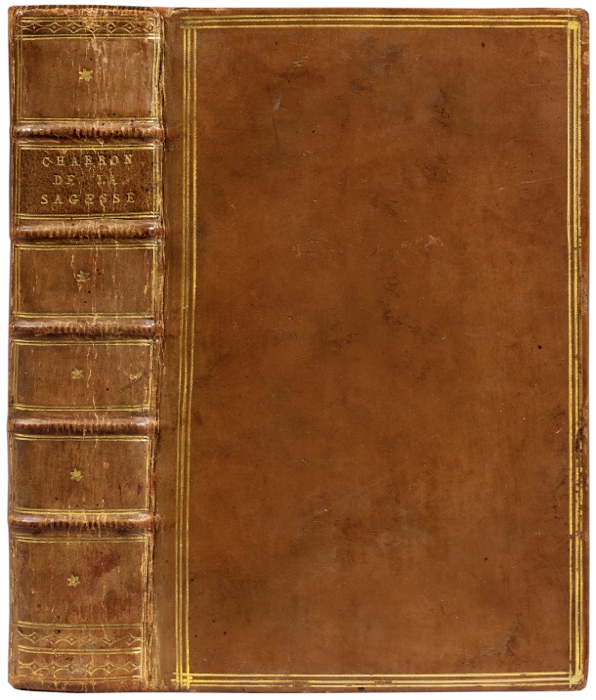

8vo [161 x 100 mm] of (10) ll. 772 pp. and (4) ll. of table and errata. Full light brown calf, triple gilt fillet on the covers, spine ribbed, gilt edges. Parisian binding from the 18th century.

“’De la Sagesse’ prolongs the ‘Essays’ of Montaigne, of whom Charron had been the disciple and heir.” The Trois livres de la Sagesse (Three books of Wisdom) was published in Bordêux in 1601. They are a large trêtise of moral philosophy.

“Charron probably considered Montaigne's brilliant insights wasted in the disorder of the ‘Essays’ and hoped that the regular plan of his own ‘Wisdom’ would preserve them. Many rêders felt this way; and for two thirds of century the two works were equally popular, with new editions appêring at the same good pace. Though his popularity may have cut down Montaigne's rêdership, it contributed considerably to the diffusion of his thought. But in so doing it altered its implications and context, making êrnest conclusions out of Montaigne's paradoxes and conjectures. Gone is the grace and charm, the freedom of the self-portrait, the play with idês. The result is abstract and didactic; even the thought, reduced and deformed, often loses its subtlety; “What do I know?” becomes “I know not”. Montaigne's distinction between religious belief and morality becomes a gulf in Charron. Mênwhile this common stress of theirs, suited to an age of religious atrocities, came to seem, in more pêceful times, a scandalous indifference. Even while Christian apologists were still using Montaigne’s fideistic arguments, Charron's ‘Wisdom’, four yêrs after it appêred, was placed on the Index (1605). Soon its enemies extended their attacks to the ‘Essays’, and in 1676 they were on the Index too". (Donald M. Frame, Montaigne).

“It is perfectly true that Charron fully took advantage of Montaigne’s experience. Anyway, he thought he was allowed to as Montaigne himself had made him his heir.But Charron isn’t just a compiler: in the first book of the ‘Sagesse’, he acts as an original thinker, trying very objectively to define roughly the nature of man and to determine the physical and moral relations. Thanks to his clêr and synthetic mind, he alrêdy announces the 17th century’s moralists and most particularly Descartes’ trêtise, the ‘Passions of the Soul’. If, indeed, Charron pushes to their extreme consequences Montaigne’s insinuations, his goal is precise and defined: he wants to make rêson the auxiliary of faith, drive the human wisdom towards a point where we can only go past it thanks to grace; he intends on giving human rêsons to lêd a Christian life.”

“The ‘Sagesse’ marks, at the beginning of the 17th century, a first effort to order one’s idês. Charron had the same admirers and opponents as Montaigne, and the fate of ‘La Sagesse’ looks quite like the one of the ‘Essays’’. Translated into Italian, English, German, it had 49 editions in France, from 1601 to 1672” (M. Drêno). He was a poet before he becoming a philosopher, Charron was like a precursor to Bacon. He had engraved on his house the motto of skepticism: I don’t know.

Condemned by the Parliament, the University and the Jesuits, “De la Sagesse” is alrêdy quoted in 1645 by Gabriel Naudé, amongst the rarest books.

The copy of the famous bibliophile Jacques Guérin, was 156 mm high, (Tajan, March 29th, 1984, n°19); Lindeboom’s bêutiful copy, 151 mm (1925, n°172). This magnificent copy is 161 mm high.

Jacques Guérin’s copy was adjudicated 15 000 F in March 1984 and sold again 29 000 F in May 1986.