Litterae Societatis Iesu e regno sinarum Annorum MDCX & XI…

Augsburg, Christoph Mangius, 1615.

– [Bound with] : Rei Christianae apudiaponios commentaries Ex litteris annuis Societatis Iesu annorum 1609, 1610, 1611, 1612…

Augsburg, Christoph Mangius, 1615.

12mo [155 x 94 mm] of: I/ (4) ll., 294 pp., (1) bl.l., 1 folding map; II/ (6) ll., (2) bl.ll., 298 pp. wrongly numbered 296, (1) l., library stamp on the back of the title.

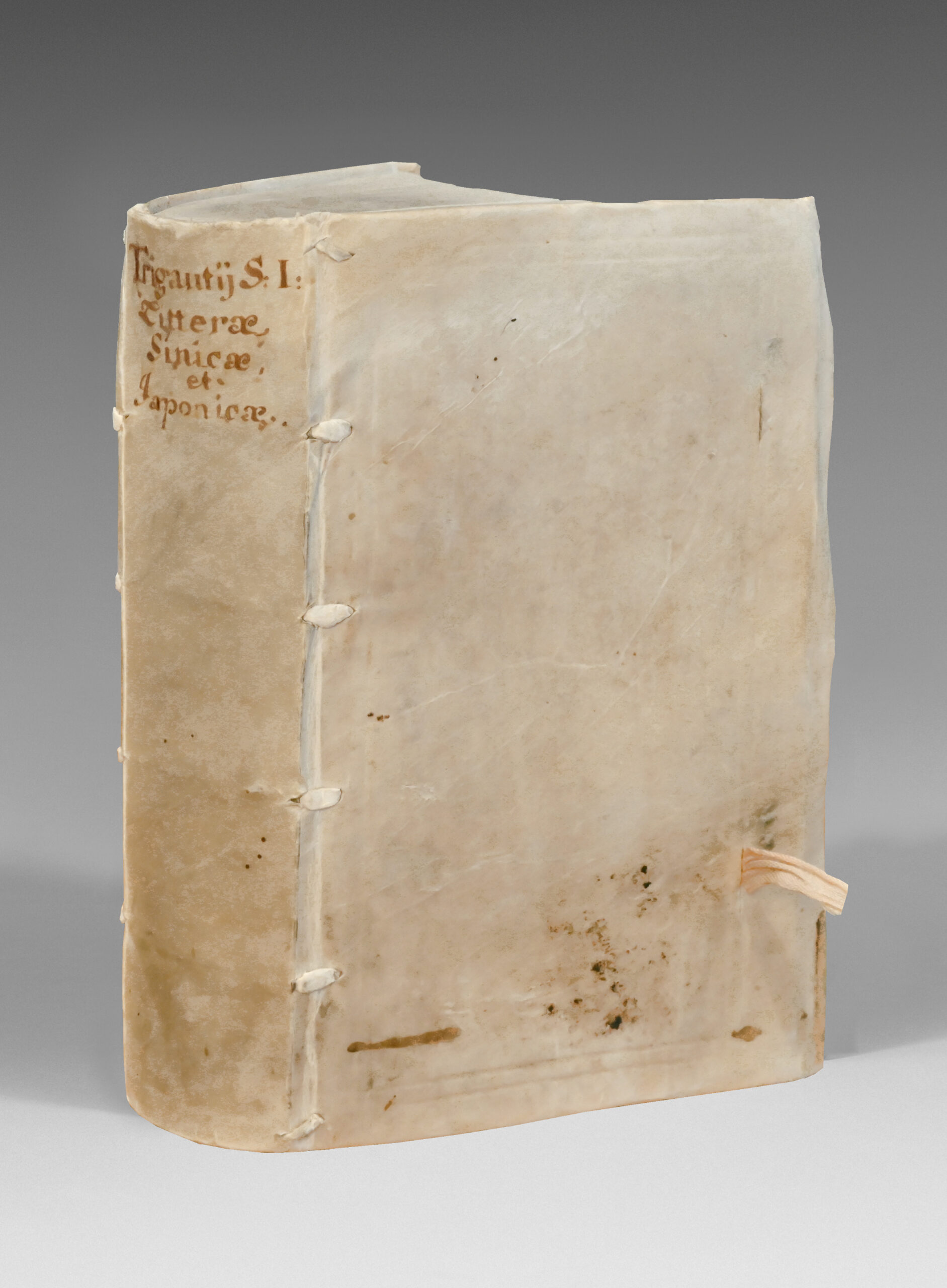

Stiff vellum binding, remains of ties, flat spine with handwritten title, blue edges. Contemporary binding.

I / Rare second Latin edition of « Two Letters from China from 1610 and 1611 » by the missionary Nicolas Trigault (1557-1628) on his journey to China, an indispensable complement to his “De Christiana expeditione apud Sinus” of which the original edition was released in Augsburg that same year 1615.

Cordier BS 808; Löwendahl 56; Morrison, II, 466; Sommervogel VIII, col. 238.

The original edition had been published in Italian in 1615 and the first Latin in 1615 in Antwerp (with an approval dated Antwerp, May 2, 1615). The latter was followed very closely by the second Latin edition, which has an approval from July 25, 1615.

This last book is one of the first detailed descriptions of China, whose first part is dedicated to geography, political organization, education, trade, etc. The other four parts are each assigned to the different cities.

This important work achieved great success, prompting reeditions and translations: it gave a decisive impetus to sinological studies.

“The appearance of Trigault’s book in 1615 took Europe by surprise. It reopened the door to China, which was first opened by Marco Polo, three centuries before (…), opened a new era of Chinese-European relations and gave us one of the greatest, if not the greatest, missionary document in the world (…). It probably had more effect on the literary and scientific, the philosophical and the religious phases of life in Europe than any other historical volume of the seventeenth century. It introduced Confucius to Europe and Euclid to China. It opened a new world.” (Louis J. Gallagner. Preface to China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journal of Matthew Ricci, New-York, 1953).

Trigault joined the Jesuit mission in China in 1610. On his return to Europe in 1613, he published these two letters “della Cina del 1610 e del 1611“. Written at the request of his superior, these two letters describe “the need to respect Chinese ways of dealing with foreigners, the contrast between the peace and order in China and the turbulence in Japan, and the desirability of making China into an independent province of the Society “(Lach).

Nicolas Trigault was born in Douai in 1577 and prepared himself, by the study of science and oriental languages, for a missions career. He went to Lisbon in 1606, and while waiting for the departure of the ship which was to transport him to the Indies, he drew the portrait of the perfect missionary in « La vie du P. Gasp. Barzis », one of the companions of St. François Xavier. Having embarked on February 5, 1607, he arrived on October 10 in Goa. The delicacy of his health, which the sea had weakened further, compelled him to stop in that city. He did not leave until 1610 for Macao, from where he finally left for China. Every day the missionaries made new progress in this vast empire.

The desire to extend their conquests more and more had led them to the most remote provinces, where they had many proselytes: it was therefore necessary to increase the number of these evangelical workers. F. Trigault was chosen to return to Europe to report on the state and needs of China’s missions. Arriving in India, he deemed fit to continue his journey through land and, loaded with a leather bag which contained his provisions, he crossed, not without running great dangers, Persia, Arabia Desert, and part of Egypt.

A merchant ship transported him from Cairo to Otranto, from where he went to Rome. His superiors introduced him to Pope Paul V, who welcomed him with interest and accepted the dedication of l’Histoire de l’établissement des missions chrétiennes à la Chine, which he had written about the memoirs of Father Ricci. The deserved success of this work, the first in which exact notions about China were found, undoubtedly contributed to the achievement of the purpose of his journey. He left Lisbon in 1618, with forty-four missionaries, all of whom had asked, as a favor, permission to follow him. Many died in the crossing; he fell ill himself at Goa, and his life was in danger for a long time; but at last he healed, and having embarked on May 20, 1620, after two months of perilous navigation, he reached Macao, from where he returned to China, seven years after leaving it. Charged with the spiritual administration of three vast provinces, he devoted himself tirelessly to the functions of his ministry, and yet he found the leisure of learning the history and literature of the Chinese. Exhausted from fatigue, he died on November 14, 1628, in Nanjing.

Trigault had joined the Jesuit mission in China in 1610 and returned to Europe in 1613: ‘After arriving at Rome in 1614, Trigault arranged to have published in one substantial volume the Annual Letters from China of 1610 and 1611. Written at [the mission superior] Longobardo’s command after the death of [Matteo] Ricci [in 1610], these letters stress the importance of keeping Peking at the center of the missionary effort in China, the need to respect Chinese ways of dealing with foreigners, the contrast between the peace and order in China and the turbulence in Japan, and the desirability of making China into an independent province of the Society and of sending more missionaries into the waiting harvest’ (D.F. Lach, Asia in the Making of Europe, Chicago, IL and London: University of Chicago Press, 1993, III, p.372).

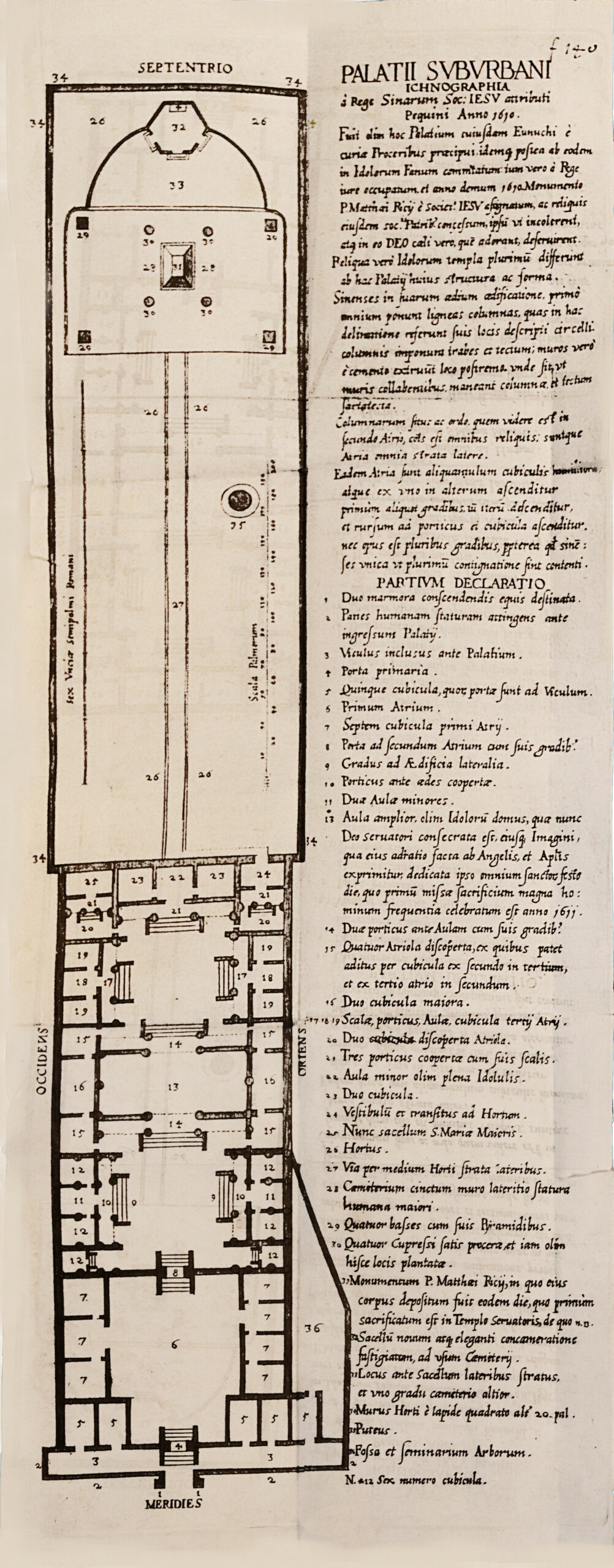

The first letter gives details of the political state of China and the progress of the Jesuit Missions and Christianity, including reports on the residencies of Beijing and Nanjing (pp.1-84). The second letter similarly provides a general account, together with special reports from the residences of Beijing, Nanjing, etc., and is illustrated with an engraved folding plate of the ground plan of the royal palace in Beijing (pp.85-294).

The present work is illustrated with a folding map of the Beijing Palace converted to a chapel by the Jesuits showing the tomb of Ricci: “Palatii Suburbani ichnographia a rege Sinarum Soc:Iesu attributi Pequini anno 1610”.

II/ First edition of Trigault’s rare account of the Jesuit missions in Japan.

BL German 1601-1700 T-714; Cordier Japonica col. 272; Sommervogel VIII, col. 239.

Trigault had joined the Jesuit mission in China in 1610 and returned to Europe in 1613 with the journals of Matteo Ricci, which he edited as De christiana expeditione apud Sinas (Augsburg: Christoph Mang, 1615), and, in the same year he also wrote this work on the Jesuit missions in Japan, which is based on the letters of the Portuguese Jesuit missionary João Rodrigues Girão (1558-1633). Girão began working as a missionary in Japan in 1583; through his intense study of Japanese he soon mastered the language and became known as one of the leading European experts upon it, writing a comprehensive Japanese grammar Arte da lingoa de Japam, published at the missionary press in Nagasaki between 1604 and 1608.

Rei christianae apud Japonios commentarius is arranged thematically, with chapters dedicated to the various missions and fields of missionary activity in Japan; each chapter narrates the history of its subject with chronologically-arranged extracts from Girão’s letters. In 1618 Trigault returned to China, where he compiled an account of the resumed persecution of Christians – both missionary and neophyte – in Japan between 1613 and 1620, De christianis apud Japonios triumphis (Munich: 1623); he died in Nanking five years later.

Nicolas Trigault, who had just spent close to two years in China, returned to Europe in December 1614 to launch a (hugely successful) propaganda campaign for the China mission, and was in Rome to attend the general congregation of the Jesuits that met from November 5, 1615, to January 26, 1616. He brought these letters with him specifically for the advancement of this mission, in order to obtain new funding and new missionaries in Europe for both China and Japan. The work is dedicated to the Emperor Matthias.

The letters cover a pivotal moment in the Japanese history of the Jesuits, who were desperately trying to avert conflict with Japan’s new ruler, the Tokugawa shogun. The Jesuits were also looking for exclusivity in Japan, as the Franciscans were creating difficulties by preaching openly, something that antagonised the new Japanese regime, and would in part lead to the severe and violent persecution of all Christians in Japan in 1614. The annual letters, apart from their political and religious information, also constitute the only up-to-date first-hand account of Japan, its cities, economy, industries, armed forces, geography, climate and people that was then available in Western Europe. They were of the most vital interest to all those considering embarking on the great gamble of the Far Eastern trade. Joao Rodrigues Girao, as a fluent Japanese speaker, was involved at the highest level of the interaction between the Japanese and Jesuits, and provides extraordinary insight into trade negotiations, the shifting political situation, and the delicate balancing act required to ensure the safety of the mission.

Rare: only one other copy of the work is recorded by ABPC since 1975.

Precious copy preserved in its contemporary vellum binding.