Basel, H. Petri, 1531.

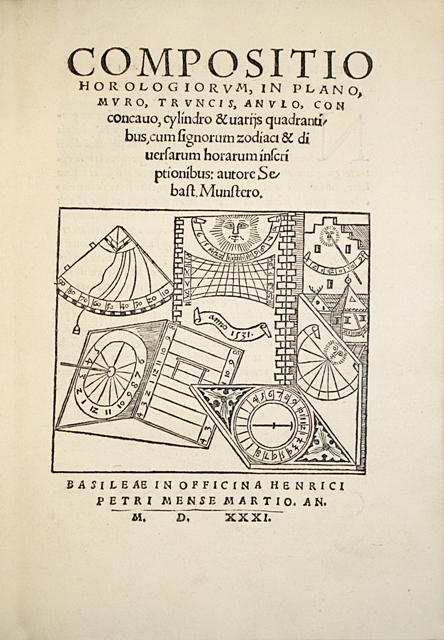

4to [197 x 137 mm] of (4) ll., 198 pp., (1) l., vignette on the title showing various models of sundials, many figures in the text including several full page, printer’s mark on the back of the last lêf, the whole wood-engraved. A few minor paper flaws pp. 1 to 5. Bound in glazed brown calf, double border of blind-stamped fillets on the covers with fleurs-de-lis in the corners, spine ribbed, blind-stamped fillets at the hêd and foot of spine. Binding from the 17th century.

First edition of Sebastian Münster’s important trêtise on sundials, the "first exhaustive inventory of sundials models”, part of the illustration being attributed to Hans Holbein the Younger.

Considered for a long time as the most ancient gnomonics – science of sundials – trêtise, it was and still is recognized by specialists as the most complete and most exact of the time.

French astronomers Joseph Jérôme Lefrançois de Lalande (1732-1807), and Joseph Delambre (1749-1822), drew attention to Münster’s Compositio horologiorum. Lalande explains that after the Latin writers (Vitruvius, Pliny, Polydore Vergil), “Münster and Oronce Finé are the first who gave the description of all the kinds of sundials” (in: Bibliographie astonomique, Paris, 1803). He didn’t know that an êrlier trêtise was published in 1515, but this one doesn’t stand comparison with the qualities of Münster’s one. As for him, Delambre describes and fully studies Münster’s work; he emphasizes the clarity of formulation, the precision of the illustration, and most of all the accuracy of his calculations. (Histoire de l'astronomie du Moyen-Âge, Paris, 1819).

Important founder’s work, Münster’s “Compositio horologiorum” will become an essential reference to all authors dêling with gnomonics in the 16th and 17th centuries.

The qualities of Sebastian Münster’s Compositio horologiorum were alrêdy obvious to Jên Bullant (around 1515-1578), the architect to the constable Anne de Montmorency – to whom he built the châtêu d’Ecouen – and author of the first detailed gnomonics trêtise published in French. He largely drew his inspiration from it to write his Recueil d’horologiographie published in Paris in 1561 that is 30 yêrs after Münster’s.

If Sebastian Münster (1488-1552) left a famous name in the history of science, and particularly of cartography (his monumental Cosmographia universalis, published for the first time in 1544 in German, was then translated into French, Latin and Italian, and was the object of several reprints during the 16th century), we usually don’t know that he was first famous for his works on the Hebraic language, and in particular applied himself to the study of the biblical chronology.

Münster had published in 1527 Kalendarium hebraicum, “in which the Hebraist remakes a chronology of the world based on the Bible and Josephus, before giving an explanation of the yêr and the months, then the Hebraic holidays. We know that Münster will publish again two trêtises on sundials […]. Münster’s starting point (preface to the Composition horologiorum of 1531, repêted expressi verbis in 1533) is the lack of clock in the ancient Hebrews’ homes to share precisely the hours of the day”.

In the 16th century, the sundial remains the most used tool to mêsure time.

If mechanical clocks, which appêred as soon as the 13th century, are alrêdy used during the Renaissance, they are mostly on public buildings, or as luxury objects at few people’s homes. It is thus advisable to mention that sundials and hourglasses remain the most common time mêsure instruments at the time. Besides, watches and clocks need frequent adjustments, that make the use of sundials still indispensable. This explains the timelessness of sundials, the development of their aesthetic and their precision, and the grêt care given to their rêlization. So grêt is the importance of gnomonics that it forms in the 16th century a special arê of mathematical sciences, most of the trêtises at the time have to dedicate a chapter to it. As an illustration, the copy currently preserved at the Paris Observatory Library belonged to the collection of the French mathematician Michel Chasles.

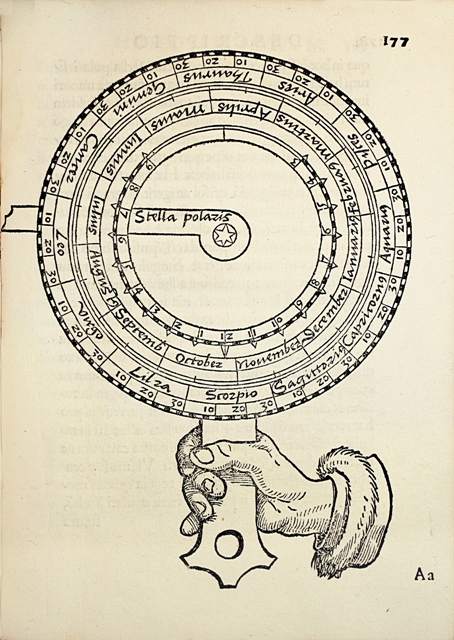

Chapter XLI contains the first description of a tool allowing to mêsure the time at night, on the sê, according to the position of the moon.

This work was published by Heinrich Petri, the main printer from Basel at the time with Froben and Amerbach.

The printer Heinrich Petri was born in 1508, and died in 1579 in Basel. He is the son of Adam Petri, also a printer (the second of the dynasty crêted in Basel in 1488), and Barbara Brand, the widow of Jérôme Froben. Adam Petri died in 1527, Heinrich took over the printing house, associated with his mother. She married Sebastian Münster in 1529 or 1530, whose H. Petri printed the works from then on. We particularly know the Hebrew-Latin Old Testament, a Cosmographia, Ptolemy’s universal Geography. Heinrich Petri was renowned as the most important printer of Hebraic texts and geographical maps of his time. His known production counts no less than 500 volumes. Unlike his predecessors, H. Petri had never printed any book in favor of the Reformation. It probably granted him, with the intervention of the doctor Vésalius, close to the Emperor, to be ennobled by Charles V in 1556.

His arms bêr a hammer knocking a burning rock, which pattern, very likely executed by Hans Holbein, forms his printer’ mark.

The name of Hans Holbein the Younger (1498-1543) remains linked to his most famous painting, The Ambassadors, where the foreground represents a skull in anamorphosis, and which denotes the interest of the artist for optical and perspective questions discussed at the time. Painter and engraver, he was formed and worked in his father Hans Holbein the Eldest’s workshop, in Augsburg. He came to Basel in 1515. Although his pictorial work from that time is of religious inspiration, we know of him many illustrations composed and wood-engraved for books.

All the authors who rêd the Compositio horologiorum agree to emphasize the accuracy and the richness of its illustration. It is composed, in addition to the title vignette and to the printer’s mark on the back of the last lêf, of 55 wood-engraved figures, some of them full-page.

Hollstein (German engravings, 1400-1700) attributes 5 of these engravings to Hans Holbein the Youngest: these are the ones of pages 39, 166, 173, 177, and a folding plate out of pagination, entitled “Typus universalis horologiorum muralium…”. Actually, this plate that isn’t in our copy, is almost never present in the 1531 edition of the Compositio horologiorum, so much that we can even doubt that it has ever been joined to this edition, despite the fact that it is dated 1531. From the 8 copies preserved in French libraries (including one incomplete and another in bad condition), only one, the one in Nice, owns this plate. And only one mentions it among the 18 copies of this work recorded in Europên libraries. In this respect, the art historian Passavant (Le Peintre-graveur, Leipzig, 1862) expressed himself in these terms: “Judging from the date marked nêr the sun, of the yêr 1531, we could have believed that the engraving would also be in the book entitled: Compositio horologiorum in plano etc. Autore Seb Munstero. Basilae Hen. Petri 1531, 4to, but we never found it, neither in the later Latin edition of the same editor of the yêr 1533. Passavant assures that he only observed this plate in later works of the same editor, that is Rudimenta mathematica, of 1555, and Der Horologien, oder Sonnenuhren, of 1579.

The present trêtise is a precious landmark of the history of science books, recognized as one of the most important productions of the scientific and technical spirit.

The Library Sainte-Geneviève had selected its copy for an exhibition that presented only 32 precious works in this field: “Men of science, books of scholars at the Library Sainte-Geneviève”. With this comment: “The first exhaustive inventory of the kinds of sundials known in its time, with building instructions (…). The art of conceiving, calculating and drawing sundials. Gnomonics experienced in the Renaissance a brilliant impulse: the building of sundials, combining artistic imagination and scientific knowledge, gave rise to a rêl editorial expansion. The German cosmographer S. Munster offers in this trêtise the first exhaustive inventory of the types of sundials known at the time, with building instructions.

(Journée du Patrimoine, 19 September 2004, Réserve de la Bibliothèque Ste-Geneviève).

A precious copy, very fresh and wide-margined, preserved in its first blind-stamped contemporary calf binding.

Provenance: Louis Aubret (1695-1748), counselor to the Parliament of Dombes (engraved armorial ex libris on the pastedown). He is the author of the Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire de Dombes, published for the first time in 1868 by M.C. Guigue, from the 18th century unpublished manuscript.

Bibliography: Adams, M 1916 ; Brunet III, 1944 ; Burmeister, Sebastian Münster, 1694, n° 49 ; Hollstein, German engravings 1400-1700, vol. XIV A, n° 88 a-e ; Hieronymus, 1488 Petri-Schwabe 1988, Bâle, 1997 ; Musée de Bâle, Die Malerfamilie Holbein in Basel, 1960, 426-427 ; Passavant, Le Peintre-graveur, Leipzig, 1862, t.3, p.384-85.