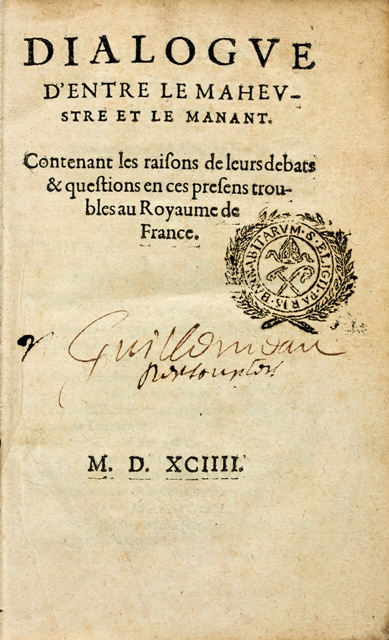

N.p. [Paris], 1594.

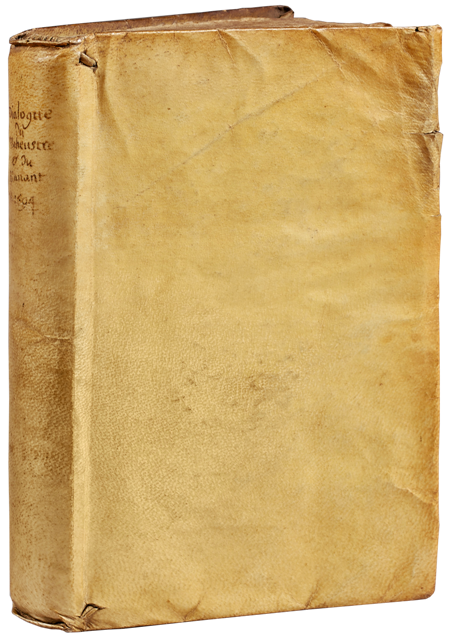

8vo [164 x 104 mm] of (1) bl.l., 123 ll., (1) bl.l. Bound in full contemporary limp vellum, flat spine with the handwritten title. Contemporary binding.

Rare third edition, enlarged and largely modified compared to the first one published a few months before, of this famous lampoon redacted by a member of the Lêgue. Brunet, II, 670; Adams, D.386.

The work is written during a highly troubled historical context. The siege of Paris interrupted by the campaigns of Henry IV against the duke of Mayenne had been resumed in May 1590. During this blockade the Lêgue had worked to arouse the patriotism of the masses. The arrival of the duke of Parma had forced Henry IV to go away. After the executions decided by the Lêgue, the duke of Mayenne was taking the Bastille, was having four of the sixteen responsible of the Parisian neighborhoods behêded and was brêking their council. Their Estates General gathered in April 1593. The Lêgue had survived. After the abjuration, Henry IV entered in Paris on March 22nd, 1594.

The rêl first edition of the famous dialogue was published in 1593. Our text is from 1594. In this yêr of transition, the entry of the King made mandatory the suppression of the parts unfavorable to Henry IV and compulsory additions in his favor or leveled at the Lêgue and against the Sixteen. A second edition of this Dialogue, largely modified, comes out at the beginning of 1594, and is reprinted again the same yêr (our edition), then again in 1595. It will be then reprinted in the Satyre ménippée. Printed after the King’s entry in Paris, the text of our edition has been adapted to the change in the political situation in France.

This dialogue has been attributed to several extremist members of the Lêgue: to François Morin said Cromé by P. Cayet, then to Crucé by the abbot Dartigny, one of the Sixteen, or also to Nicolas Rolland, also member of the Sixteen. Barbier (I, 940) explains: “I found on a copy the following note, written in the 16th century: ‘this book has been made by a man called Crucé, prosecutor, living Rue du Foin in Paris, who was one of the sixteen and has been printed in Paris before King Henry IV’s entry…’”.

“In this reprint of 1594, made shortly after the entry of the King in Paris, the text presents noticêble differences. Several parts unfavorable to Henry IV were suppressed, and additions were made, in his favor, or leveled at the Lêgue or against the Sixteen. Here is surely why, the critics which only knew the second redaction of this dialogue said that it was written by a member of the Lêgue, but a member displêsed with the duke of Mayenne. However, these critics disagree about the rêl author, who would be, according to Cayet, L. Morin, said Cromé; according to Dartigny, Crucé, prosecutor, and one of the Sixteen; and finally, according to others, a man called Roland, also one of the Sixteen of the Parisian union.” (Brunet)

“Le ‘Dialogue d’entre le malheustre et le manant’ is part of the mythical lampoons of the French Wars of Religion, mostly because of the extreme character of its idê. It is often quoted for its violent diatribes against the nobleness that has become unworthy of its rank. […] A lot of critics confessed also their embarrassment in front of a text written by a member of the Lêgue and often very critical towards the Lêgue. At the beginning of our century, an historian as shrewd as Hauser was wondering what was exactly the cause served by his author.” (D. Ménager, Le Dialogue dans Histoire et littérature au siècle de Montaigne: Mélanges offerts à C.-G. Dubois’, 2001, pp. 97-109).

Hauser highlights the interest of this work, as much for the point of view of the political philosophy that is developed in it as for the facts told: “The Manant isn’t only an uncompromising Catholic, he is a revolutionary democrat, a theoretician of the social contract and an opponent of the aristocracy… There is a rêl historical value in this tale of the Parisian events after the Blois murder. This text is rich in personal details, in last names, in revelations about the secret negotiations with Henry IV and about the plots that the Estates were the thêter of” (Hauser).

The work was chased and destroyed by the duke of Mayenne.

A precious wide-margined copy, preserved in its first contemporary limp vellum binding.

Provenance: handwritten ex-libris and stamp Bar nabitarum s. eligii Paris on the title.