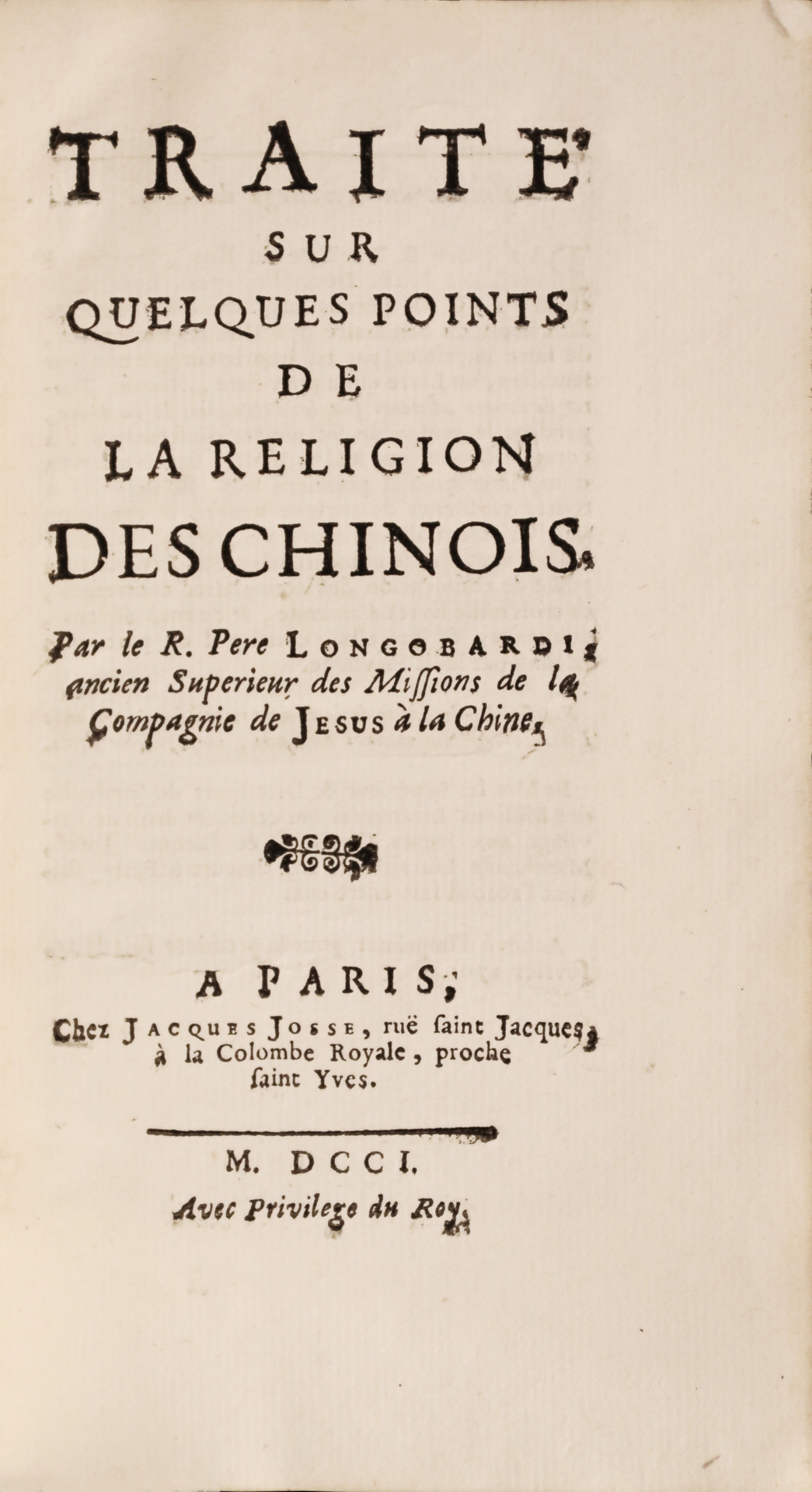

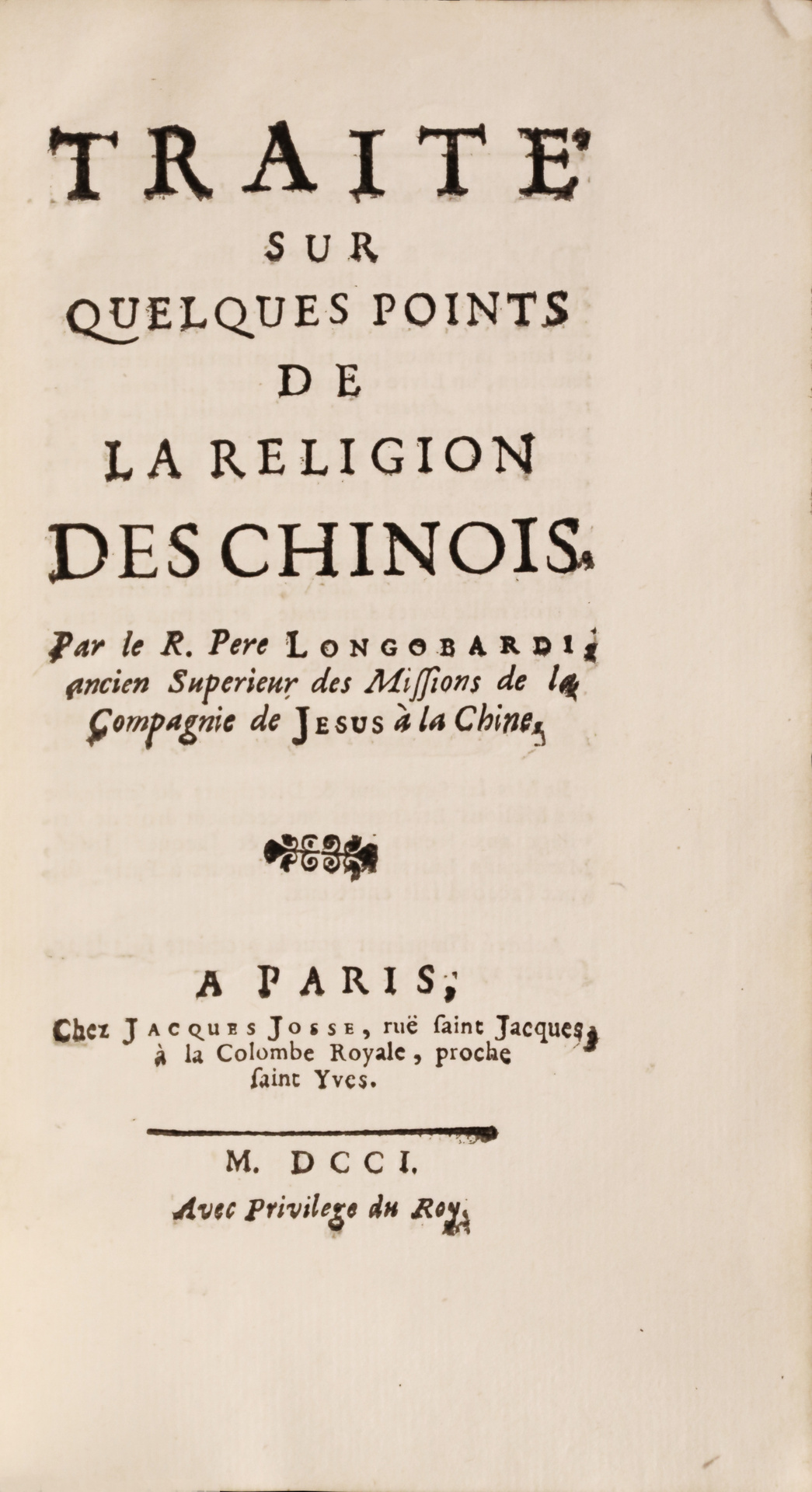

Paris, Jacques Josse, 1701.

– [With] : Copie d’une lettre de Monsieur Maigrot à Monsieur Charmot, du II Janvier 1699 reçue à Paris en Août 1700. Elle montre la fausseté de ce que le Père le Comte a écrit touchant la Religion ancienne des Chinois. 1700.

– [With] : Suite du journal historique des assemblées tenues en Sorbonne, pour condamner les Mémoires de la Chine.

12mo [157 x 87 mm] of (2) ll., 100 pp.; II/ 88 pp., tear p. 25; III/ 45 pp. Granite-like brown calf, spine ribbed and decorated with gilt fleurons, mottled edges. Contemporary binding.

First edition of this study on the religion of the Chinese by the successor of Matteo Ricci at the head of the Jesuit mission in China.

De Backer & Sommervogel IV, 1932; Quérard V, p. 347.

“The Directors of the Seminary of the Foreign Missions have obtained the privilege of having printed ancient Treatises of various authors on the ceremonies of China. The first they publish is that of Father Longobardi, Jesuit, who at his entry into this Kingdom read the four Books of Confucius, & noticed that the idea that various Commentators gave of Xangti was opposed to the divine nature. But because the Fathers of his Company, who had been doing the Mission for a long time in these countries, had told him that Xangti was our God, he rejected his scrupules, imagined that the difference between the text thus heard, & the Chinese comments, only came from the mistake of some interpreter, & remained thirteen years into this thought.

After the death of Father Matteo Ricci, he was given the full responsibility of this Mission, & received a letter from Father François Passio, Visitor of Japan, who was warning him that in some Books composed in Chinese by some of their colleagues, there were some errors similar to those of the Gentiles. This opinion of Father Passio increased the doubts of which his mind had formerly been divided, & led him to educate himself so that he could discover the truth.

The functions of his Charge, having obliged him since to go to Beijing, he found F. Sabathino de Urbis in the same scruples, & conversed with him about it. During the course of these disputes Father Jean Ruiz returned from Japan, & arrived in China with a great challenge to see these difficulties cleared up, & these questions decided […].

The three Jesuits worked according to the intention of Father Visiteur. Fathers Pantoya, & Banoni took the affirmative, & tried to prove that the ancient Chinese had some knowledge of God, of the soul & of Angels.

Father Sabathino took the negative, & maintained that the Chinese haven’t known any spiritual substance, distinct from the matter, & that consequently they have known neither God, neither Angels, neither reasonable soul. Father Sabatino sent these two treatises to Father Longobardi & to the other Jesuits of China, to examine them & to confer on them with the Christian Scholars & with the Gentiles.

At the same time F. Ruiz composed one in full accord with F. Sabathino’s feeling. F. Longobardi received these four treatises subsequently, read them, confer on them with his colleagues of China, & with the Christian Mandarins, & still judged that the feeling of F. Sabathino & Ruiz was the safest. He conferred on it again after with the Gentiles Doctors, & founding himself perfectly informed, he composed the treatise of which I’m making an excerpt.

He explains first of all the doctrine of the authentic Books of China, & after a full exam of the details they contain, he concludes that it is obvious that the Chinese have never known any spiritual substance, distinct from the matter, as are God, the angels, & the reasonable soul, & that they have known only a universal, immense, & infinite substance, whence emanates the primitive air, which by taking on different qualities, sometimes by movement, & sometimes by rest, becomes the immediate matter of all things.

All of this clearly shows which spirits the Chinese regard as Gods. According to them all that is & all that can be comes from Taikie, which contains in itself the Li, which is the raw material, or the universal substance of all things; & the primitive air, which is the next material. From the Li, as Li, emanate piety, justice, religion, prudence, & faith. From the Li qualified & united with the primitive air, emanate the five elements with all the corporal figures; so that according to the Chinese Philosophy, all things, physical and moral, come from the same source.

The Chinese since the beginning of their Empire have worshiped the Spirits & have offered them four kinds of sacrifices. The first was made to the Sky; the second to the spirit of the six principal causes, that is to say the four seasons, the warm, the cold, the sun & the Moon, the stars, the rain & the drought. The third to the spirits of the mountains & of the rivers, the fourth to the spirits of the illustrious Men.

The consequences that Father Longobardi derives from these principles, are that all the spirits that the Chinese adore are the same substance with the things to which they are united; that all these spirits have a principle; that they will end with the world, that these Spirits, or Gods, are in relation to their being of equal perfection; & finally that they are without life, without science, & without freedom.

Father Longobardi, to convince everyone that this is the true doctrine of the Chinese, reports the testimonies of their most famous Doctors, who teach that there are no other spirits than natural things.

He proves in the 16th Section that Scholars are Atheists, that they persuade themselves that the world was made by chance, that fate regulates everything, & that men after their death enter into the void of the first principle, without which there is no reward for the good, nor any punishment for the evil; which he confirms by what has been genuinely admitted to him by several Pagan Scholars, & by several Christians, during the lectures he has had with them on this subject.” (Le Journal des Savans, 1701, 147-149).

Nicolo Longobardi was Ricci’s successor as superior general of the mission in China.

He raised objections to the use of the Confucianist terms ‘Tian’ (Heaven) and ‘Shangdi’ (Sovereign on High) which had been favoured by Ricci as valid terminology for preaching to the Chinese. Longobardi’s followers were concerned that the Catholic catechism would be diluted by a Confucianist interpretation, as well as by the ongoing veneration of ancestors. The debate was resolved in 1628 at a convention in Jiading, where it was decided that the veneration of ancestors would be permitted (i.e. it was not a pagan superstition), and the use of Confucian terms was banned.

‘This work was translated and printed by the directors of the Foreign Missions. The King’s Library owns a copy with handwritten notes by Leibnitz’ (Quérard).