London, Printed for the Author, John Rivington, 1755-1760.

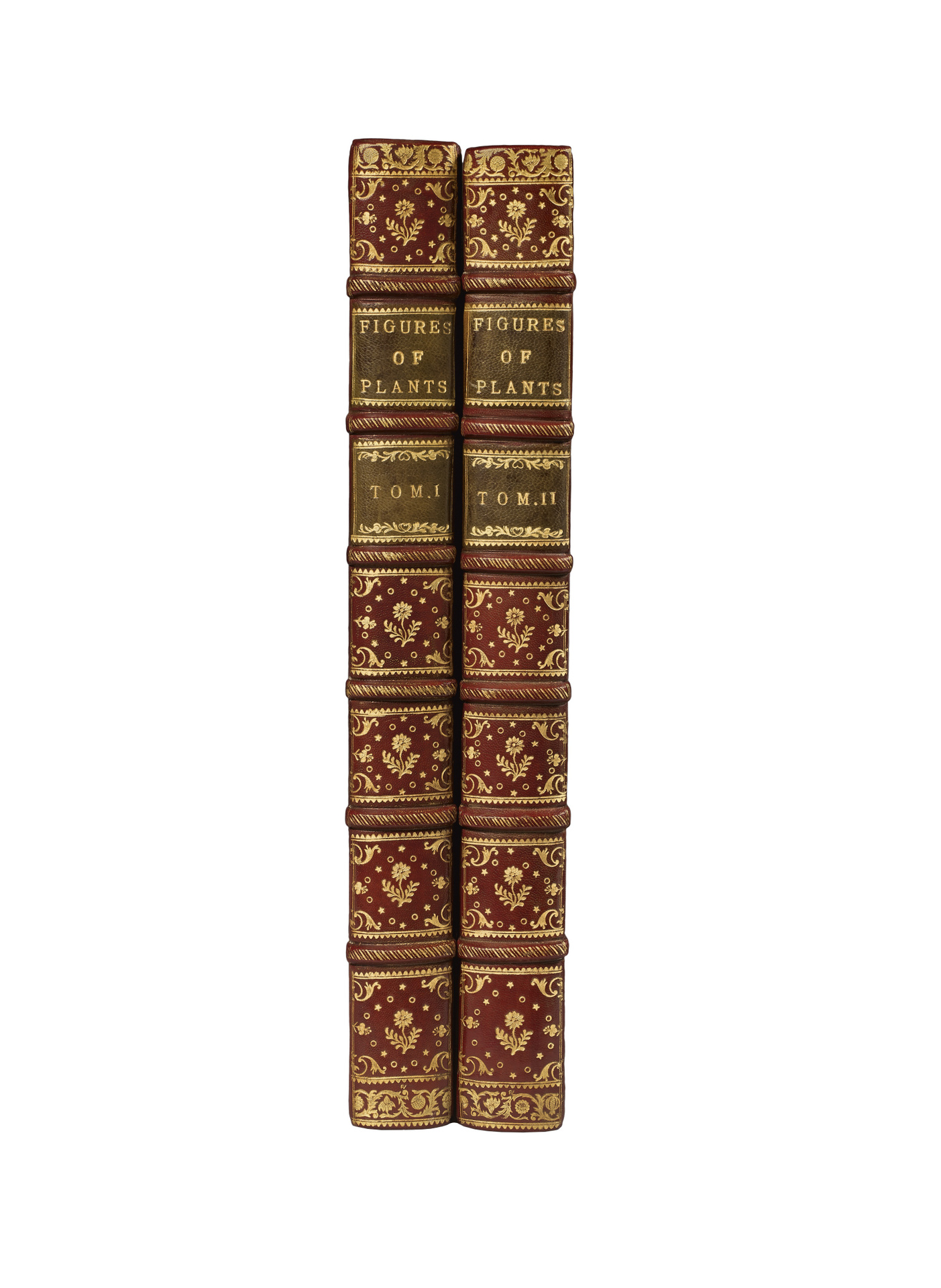

2 folio volumes [410 x 252 mm] of: I/ (3) ll., 100 pp. of text, 150 full-page plates; II/ (1) l., pp. 101 to 200, plates 151 to 300 including 2 folding, (2) ll.; 3 first ll. of volume I restored and remargined without loss, 5 pl. slightly foxed, 8 browned or stained, small tear to 1 folding pl. without loss. An unsigned drawing in ink has been bound p. 30 of volume I. Red quarter morocco with small corners in cream vellum, spines ribbed and decorated, olive morocco lettering pieces, gilt edges. Later binding.

First edition illustrated with 300 very beautiful copper-plates out of pagination by Jefferys, Mynde, Miller…, including 2 folding, all finely colored at the time.

Brunet, V, 1718; Nissen, 1378; Pritzel, 6241; Graesse, Trésor de livres rares, p. 525; Great Flower Books p. 121; Dunthorne 209; Henrey 1097; Hunt 566; Stafleu and Cowen TL2 6059.

Splendid collection of flowers and plants delicately colored at the time.

Philip Miller (1691-1771) was a great admirer of Linnaeus whose principles and nomenclature he adopted from 1768 onwards. This work was begun in 1755 and completed only 5 years later.

Miller succeeded his father in 1722 as superintendent of the garden of the Apothecary Company in Chelsea and, under his direction, this rich establishment soon became the richest in Europe for foreign plants.

It is thanks to his care that a large number of exotic plants have been acclimatized successfully in England; and his numerous and multiplied relationships with the most famous botanists, either in Europe, or in the Indies, have greatly helped spread the botanical discoveries. He first made himself known with some memoirs inserted in the Transactions philosophiques; but his Gardeners Dictionary, published in 1731, often reprinted, sealed his reputation. Linnaeus said that this book would be the dictionary of botanists, rather than that of gardeners. The author had the unusual happiness of giving thirty seven years later the eighth edition. In the first ones, he had only followed the methods of Ray and Tournefort; but in the 1768 edition, he used the principles and nomenclature of Linnaeus, of which he ended up becoming one of the most zealous admirers.

Originally conceived as a complement to an earlier publication, Miller’s work “is a sufficiently complete work and may be rated on its own merits” (Hunt).

In the preface, Miller explains his intentions to publish a plate for every plant of every known genre, but he abandoned this project in order to devote himself to “…those Plants only, which are either curious in themselves, or may be useful in Trades, Medicine, &c. including the Figures of such new Plants as have not been noticed by any former Botanists.“

“The plants illustrated were either engraved from drawings of specimens in the Chelsea Physic Garden or drawings supplied by Miller’s numerous correspondents, including John Bartram, the Pennsylvania naturalist (cf. plate 272), and Dr. William Houston, who travelled widely in the Americas and West Indies and bequeathed Miller his papers, drawings, and herbarium (cf. plates 44 and 182). For the plants drawn from examples in the Garden, Miller employed Richard Lancake and two of the leading botanical artists and engravers of the period, Georg Dionysius Ehret and Johann Sebastian Miller.

Like Miller’s ‘Catalogus Plantarum’, many of the etched and engraved plates are delicately printed in colour to give a more life-like impression after hand colouring.”

The work was published by subscription, in 50 monthly issues, each containing 6 plates, between March 25, 1755 and June 30, 1760.

The work was printed again in 1771 and in 1809.

Very beautiful copy from P. Barfoot’s library with handwritten ex-libris.

Complete copies of this first edition are rare.