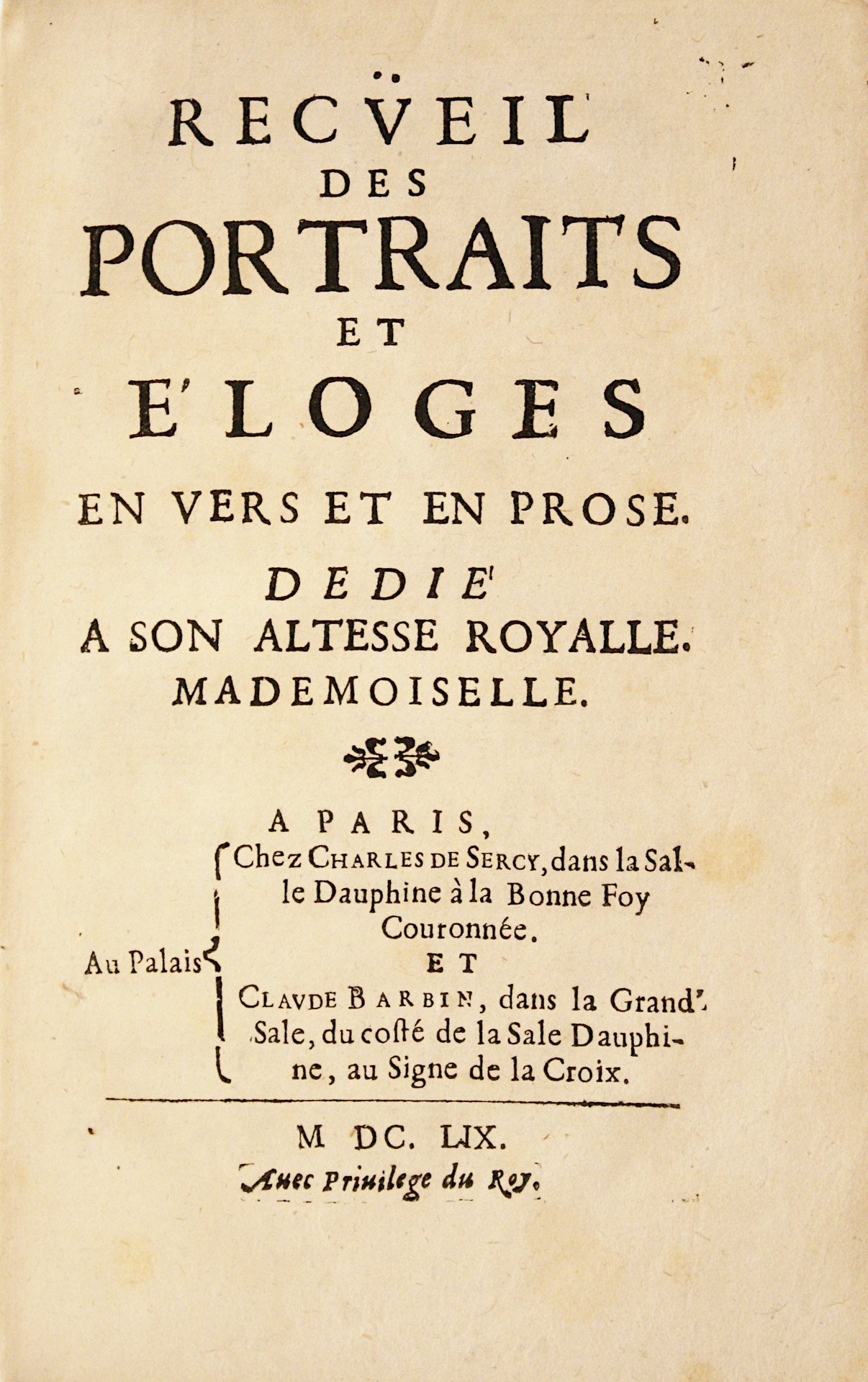

Paris, Charles de Sercy et Claude Barbin, 1659.

2 volumes 8vo [166 x 102 mm] of: I/ (16) ll. including 1 frontispiece, 452 pp. misnumbered 454 (pagination jumps from 16 to 25, from 40 to 31, from 258 to 257, from 355 to 362); pp. 455-916 misnumbered 912 (pagination jumps from 758 to 755), 3 pp. for the Clef des noms des portraits qui sont abregez dans la galerie de peintures.

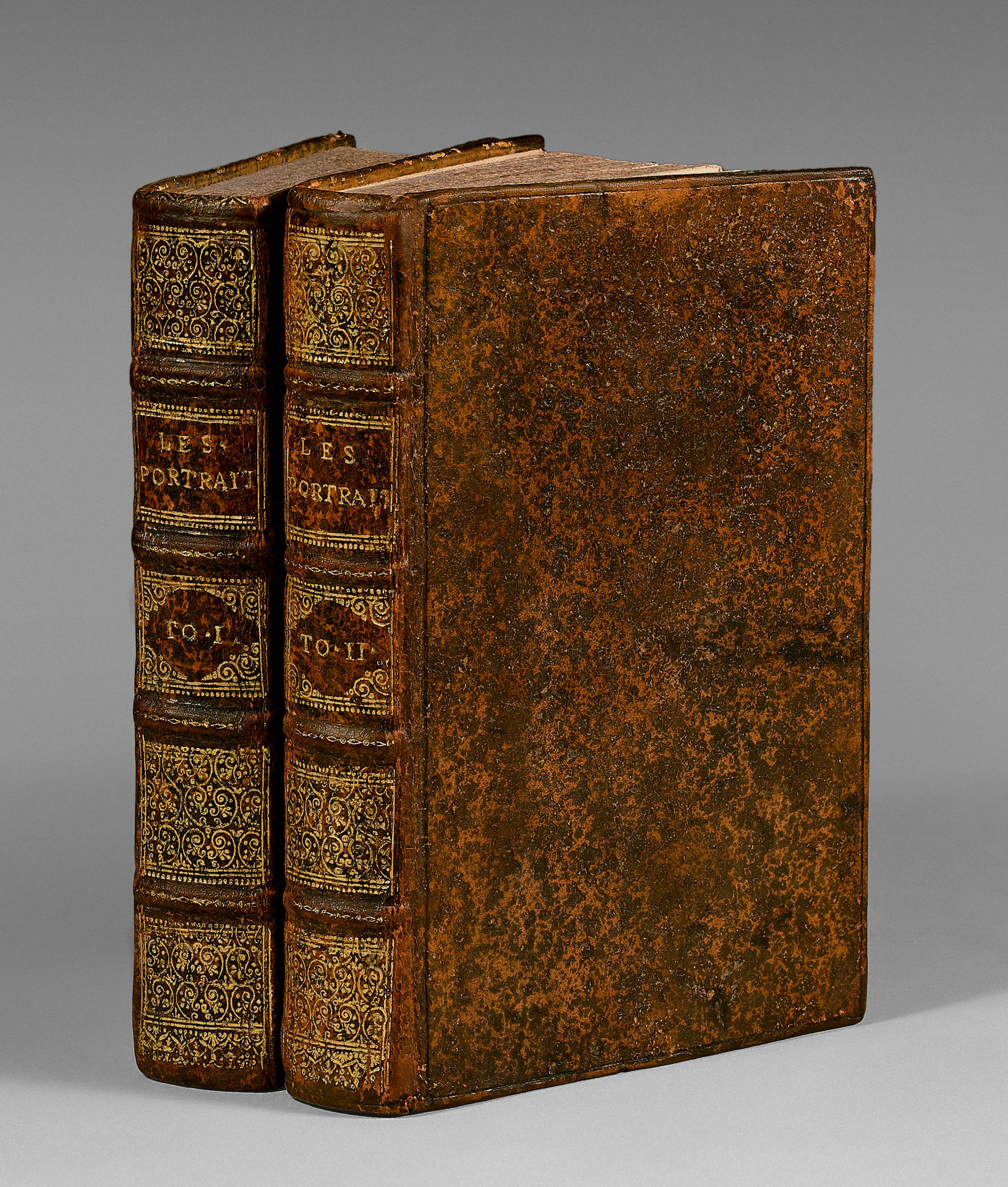

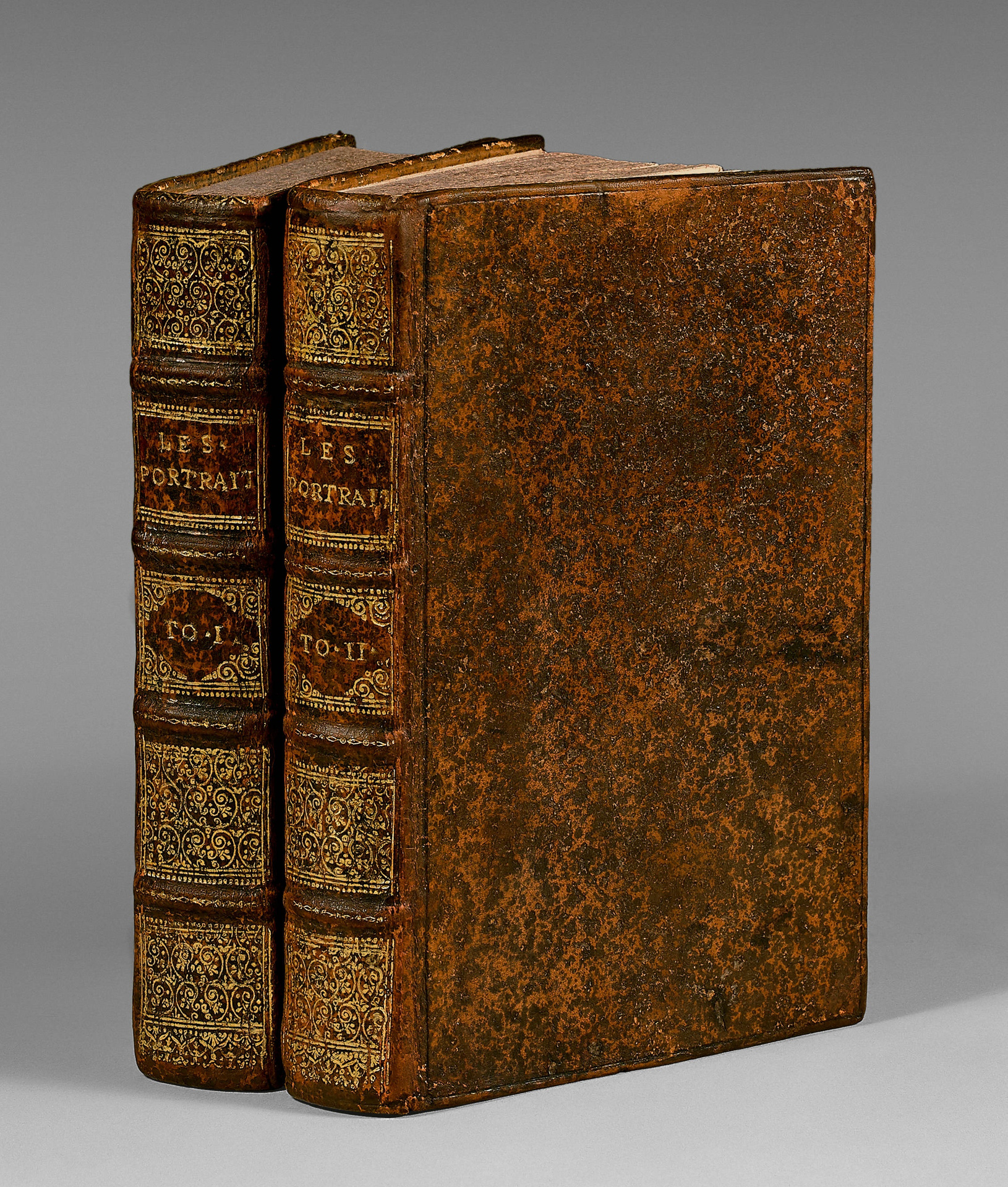

Brown granite-like calf, blind-stamped fillet around the covers, spines ribbed and decorated à la grotesque, sprinkled edges. Contemporary binding.

Legendary first edition from the century of the “Precieuses”, the second with many additions, and one of the rarest books of 17th century French literature, which has been re-edited and studied many times during the 20th and 21st centuries. (B.n.F – Hachette re-edition on June 1st, 2012, Hermann re-edition on May 16th, 2013, etc…).

Rahir, Bibliothèque de l’amateur, p. 607; Tchemerzine, IV, p 938; Lachèvre, Bibliographie des recueils collectifs, II, pp. 106-112: 103 portraits including 82 new. Edition b, with unique pagination described by Denise Mayer in Bulletin du Bibliophile, 1970, pp. 140-142.

The same year was published in Caen a volume in a 4to format under the title “Divers Portraits”. It only contained 59 portraits.

This collection presents 103 portraits of which 82 are new with the two most famous ones:

– that of Madame de Sevigne written by Madame de La Fayette here in first edition. This portrait constitutes the first printed text of Madame de La Fayette.

– that of La Rochefoucauld by himself, first printed text of the author of the “Maxims”.

The collection presents besides 16 portraits written by the “Grande Mademoiselle” (1627‑1693).

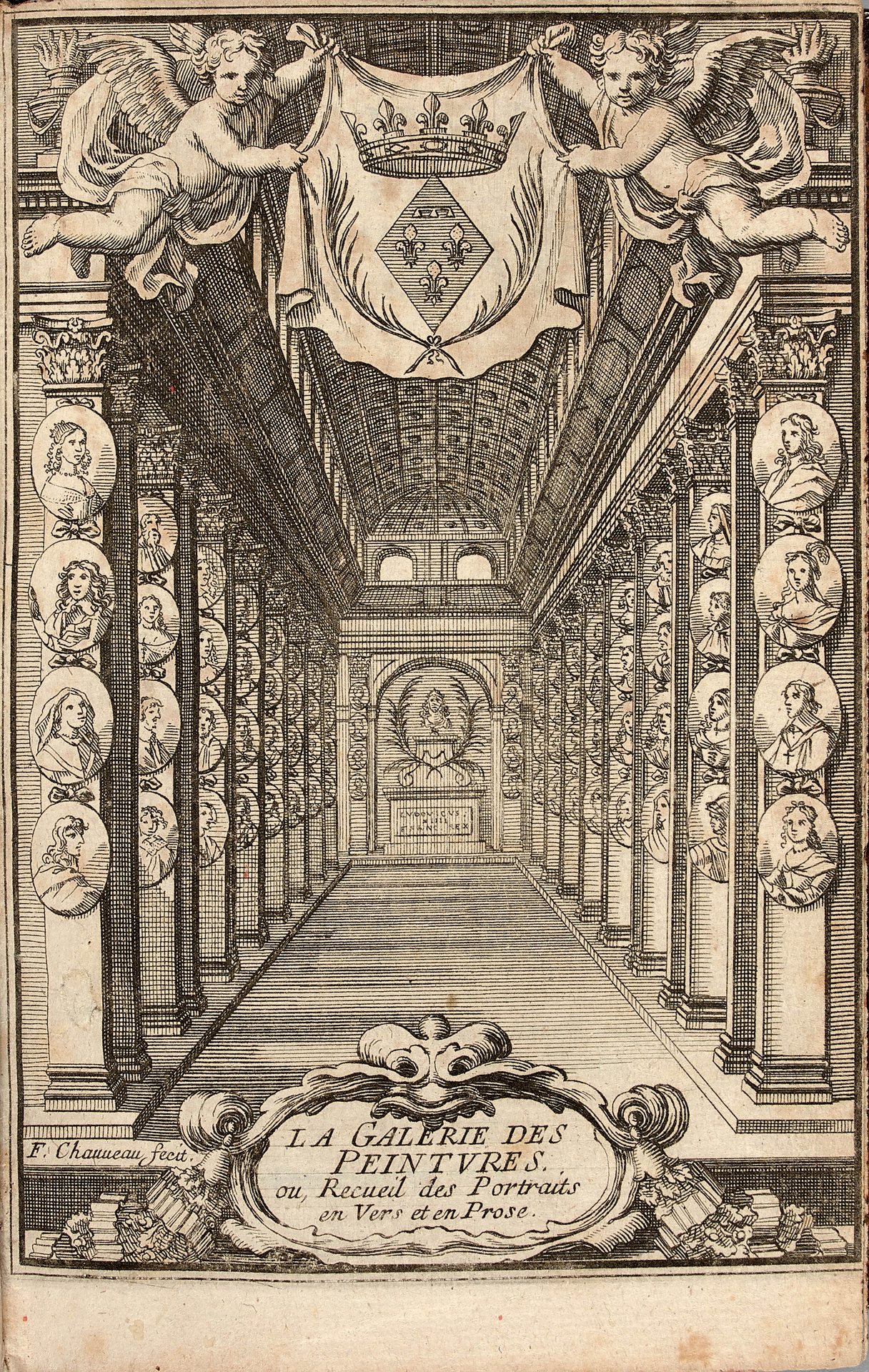

These two volumes are illustrated with a superb frontispiece, true gallery of portraits, bearing the arms of the Duchess of Montpensier.

It took until the in-depth study of Denise Mayer dedicated to this so important book in the century of the “Precieuses”, the first among French literature to describe exclusively portraits and personalities, preceding from a few years the La Bruyère, La Rochefoucauld and others, to discover in this edition in 912 pages a true first edition differing from the Divers Portraits published in Caen that same year.

This collection is of the utmost rarity.

Brunet only mentions one copy, that of the Libri sale in 1857 (II, 770).

Tchemerzine (IV, 938) mentions two of them including the Rahir copy with the arms of La Grande Mademoiselle brought to the colossal price of 18 000 Fr Or on the Fontaine catalogue of 1879. A book of bibliophily was then negotiated from 10 F Or , 1 800 times less.

This copy in contemporary binding is the only one to appear on the market in this condition for more than half a century.

Jacques Guérin highlighted Les Divers Portraits in his famous sale of 1984 and placed the title of this volume decorated with the arms of the Grande Mademoiselle “as the frontispiece of his catalogue”.

This famous text has been the subject of many recent studies .

On May 16, 2013 was published the study and critical edition of the “Divers portraits” by Sara Harvey presented as such by the editor:

“This work has a dual purpose: it presents in the first part a reading of the Divers portraits by Mademoiselle de Montpensier and provides, in a second time, the first complete critical edition of this collection of literary portraits published in a limited number in 1659. The proposed study is based on the founding ambiguity of the Divers portraits: work of circumstance witness of a fashion of the literary portrait which lasted less than three years (1656-1659) and book of historical and memorial preaching dedicated to the glory of Anne-Marie-Louise de Montpensier.”

Let’s finally recall that the most comprehensive recent study appeared in February 2013, work of Leah Chang (George Washington University):

« In this first critical edition of Mademoiselle de Montpensier’s Divers portraits (1659), Sara Harvey makes available to scholars a lesser-known work by Anne-Marie-Louise d’Orléans, duchesse de Montpensier.

Known as “La Grande Mademoiselle“, Mademoiselle de Montpensier is most famous for her proximity to the throne during the reign of her cousin, Louis xiv, for her role in the Fronde, and for her Mémoires (first published in the eighteenth century). The Divers portraits are particularly distinctive as a collaborative work, for the 1659 volume contained literary portraits and self-portraits authored by both the duchess and those in her circle during the years 1653‑1657. In an extensive introductory study that precedes the critical edition, Harvey immediately lays out the interpretive question that underpins an analysis of both the material volume and the historical circle that generated it. Why, she asks, was the book published as an ornate, limited edition livre d’apparat (akin to a highly decorative vanity publication) when the vogue for this kind of literary portrait would last only about three years in mid-century? And what is the scholarly interest for such a book today?

As Harvey outlines, the critical approaches to the Divers Portraits have generally taken two forms. On the one hand, literary historians have been interested in the Divers portraits principally as representative of the genre and form of the literary portrait it elaborates, its production among a circle of mondain participants, and its reception among a narrowly defined and elite audience. On the other hand, historians of the book have approached the Divers portraits as a “patrimonial object” whose historical value is largely found in its memorializing objectives. Harvey situates her presentation of the Divers portraits between these two critical perspectives. How, she asks, does the collection walk the line as witness both to an aristocratic, memorial endeavor and to the fleeting mondain tasse for the literary portrait?

At the heart of the Divers portraits, Harvey argues, is Mademoiselle de Montpensier herself. When she was born in 1627, the birth of the future Louis xiv was still nine years away. As the only child of Louis xiii’s younger brother, Gaston d’Orléans, and Marie de Bourbon, Mademoiselle de Montpensier was, as a young child, the scion of the Bourbon dynasty. Her prominent identity as the “first child of France” earned her international visibility, an exceptional education, and an enviable position as both object and patron of countless writers and artists. It was in this culturally dynamic milieu during her early years, Harvey shows, that Mademoiselle first became the object of numerous visual and literary portraits, which worked to celebrate the young duchess as the flower of French nobility within a genealogical narrative of royal dynasty, inheritance, and female heroic power. After the Fronde (1648-1653), the duchess’s interest in the literary portrait took on a different dimension. During her period of exile, beginning in 1653, the composition of portraits served to entertain the duchess, but also to explore and construct the centrality of her own royal identity. By assembling the Divers portraits and printing the volume in limited edition with careful attention to its aesthetic design, Mademoiselle de Montpensier marked the creation and publication of the literary portrait as an exclusive affair in which she was the central and directive figure. In its material production, then, the volume of the Divers portraits became both the medium and the material incarnation of the duchess’s self-promotion. Harvey divides her book into two distinct sections : an extensive, three-part introduction, followed by a critical edition of the 1659 text. The introduction is particularly notable and exhaustive in its detail. The three parts trace the production of the Divers portraits from its first publication to its reception post-facto through the nineteenth century. Part One covers the origins of the literary portrait, the intersections of the development of the genre as it was intertwined with Mademoiselle’s personal history, the moral and political uses of the portrait, and the ways in which the duchess used the portrait to develop a personal mythology. Part Two analyzes aspects of the material production of the book, including paratextual material, frontispieces, the uses of titles and ornaments, the arrangements of the portraits within the collection, and dedications. The third and final part examines the reception of the Divers portraits from the seventeenth century onward. Harvey closely compares the Divers portraits to the Recüeil de portraits et éloges, another portrait collection also published in 1659, with which the Divers portraits is often confused (the publication in the same year of both collections testifies to the popularity, if ephemeral, of the genre).

This comparison highlights the précieux backdrop that informed the composition and publication of literary portraits, and shows how the two collections followed two distinct modes: while Mademoiselle’s Divers portraits was indeed inspired by the literary pastimes of the aristocracy, it also sought politically to glorify and memorialize that elite, while the Recueil belonged more properly to the mode of “gallant literature.” After a discussion of seventeenth-century commentaries on the portrait, Harvey concludes the introduction by tracing the nineteenth-century reception of the Divers portraits, emphasizing in particular the ways in which its material form—as livre d’apparat—ensured its continued attention by historians of the book and paved the way for its historical reception as a memorializing endeavor, as distinct from the category of littérature mondaine in which the literary portrait could otherwise be inscribed… »

(Leah Chang – George Washington University).

Remarkable copy of this famous book with wide margins (height 166 mm), the only one preserved in its strictly contemporary binding to appear on the market for more than half a century.

It is complete with the key printed at the time, “which we have not seen anywhere” said Rochebilière (Cat. I, 1882, n°713).

From the libraries of Louis de Monmerqué (1780-1860), with autograph note, and Jacques Dennery, with ex-libris.