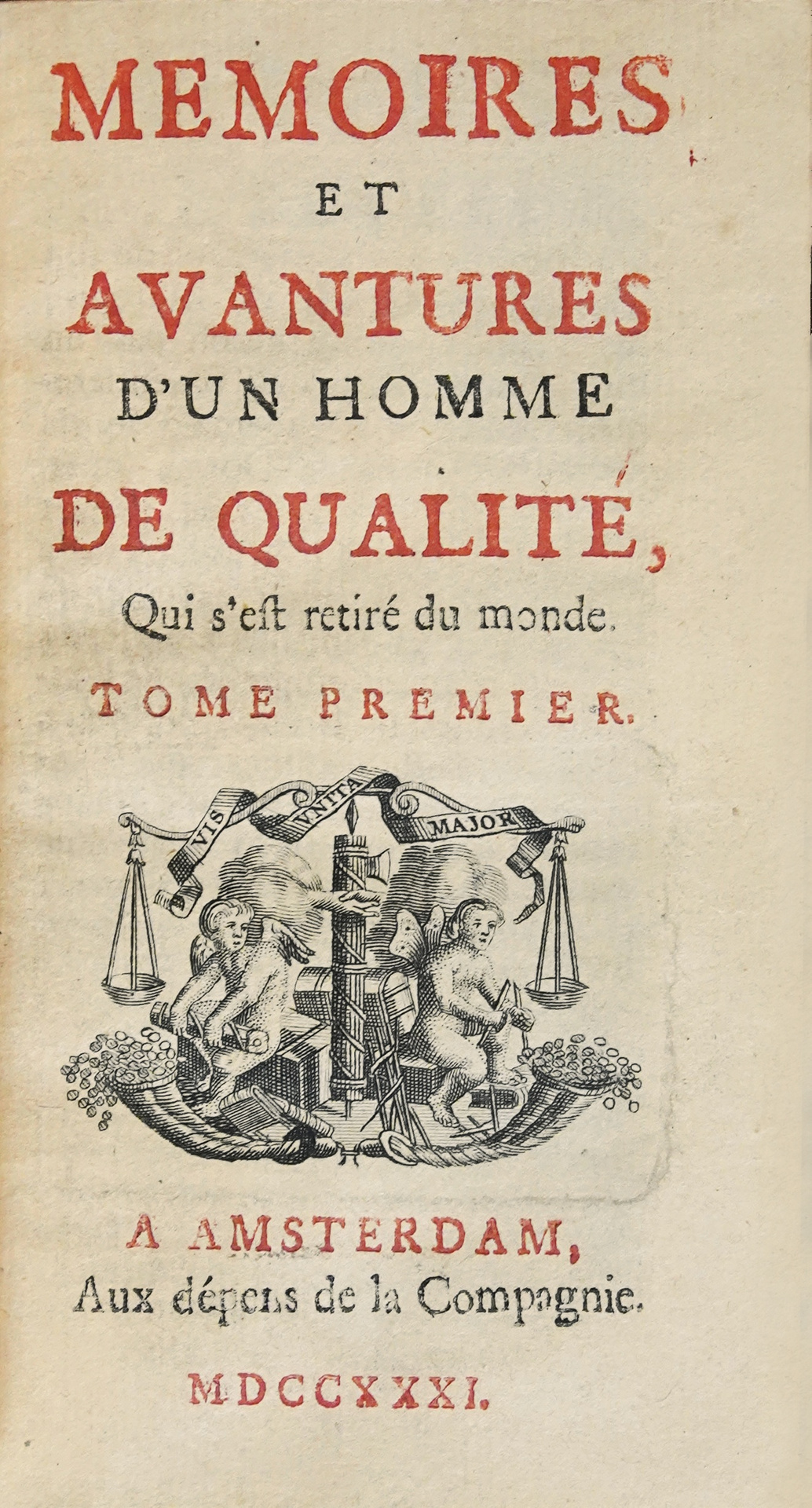

Amsterdam, Aux dépens de la Compagnie, 1731.

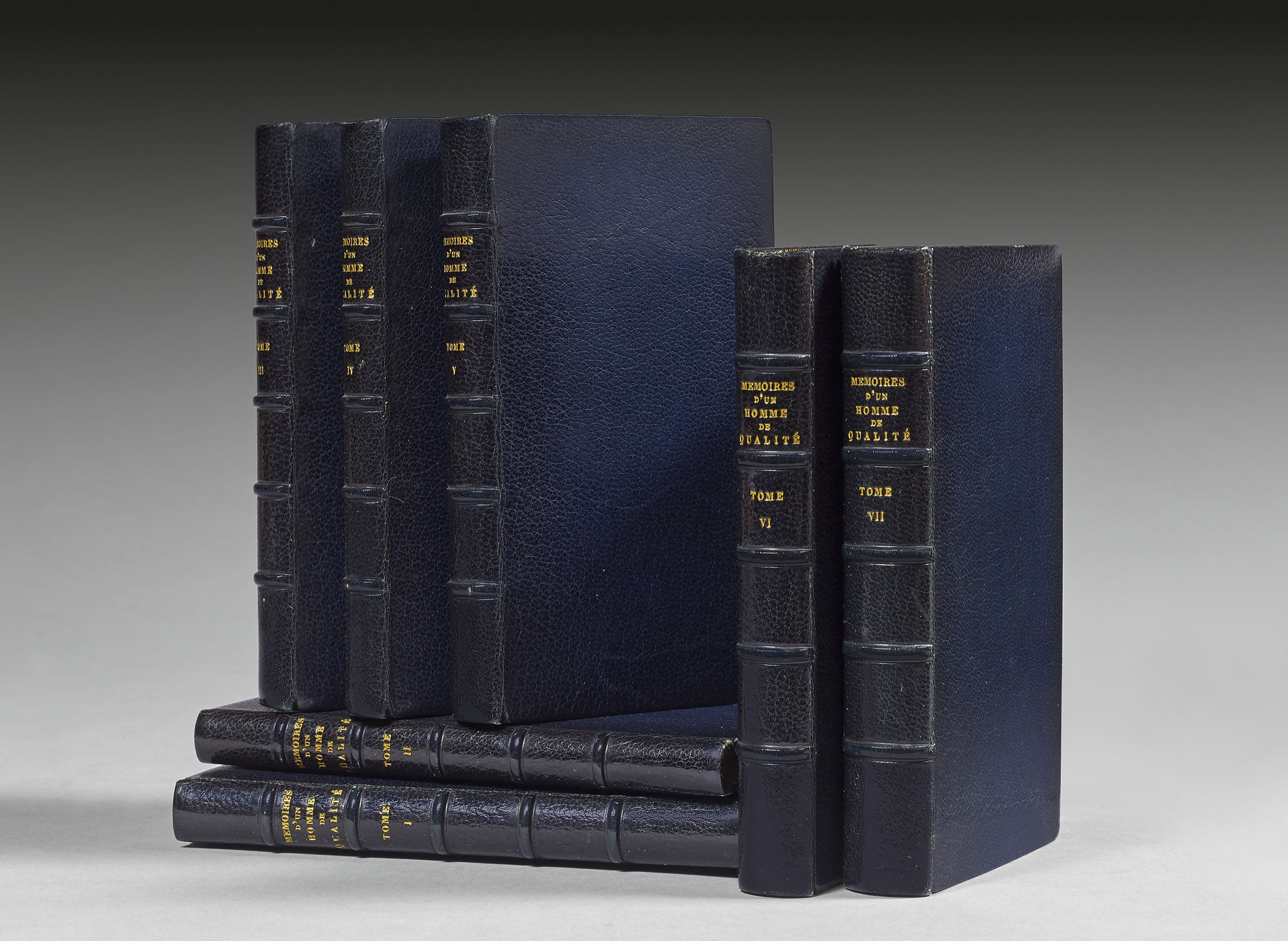

7 volumes in small 12mo [127 x 73 mm].

« Seven vol. small 12mo of (2) ll., 218 pp and (1) bl. l, 173 pp. and (1) bl. l. ; (1) l. et 232 pp. ; (1) l., 221 pp. and (1) bl. l. ; (4) ll. of which 1 bl. and 288 pp. ; (2) ll. of which 1 bl. and 283 pp., (2) ll. of which 1 bl. and 344 pp. (The bookbinder did not keep the blank leaves).

The seventh volume contains the first edition of Manon Lescaut.

The volumes I, III, V and VII are illustrated with a copperplate vignette and volumes II, IV and VI with a woodcut fleuron. Only the last three volumes have a half-title, here not preserved by the binder.» (Tchemerzine).

Full Jansenist blue morocco, spines ribbed, inner border, gilt over marbled edges. Binding by Thibaron-Joly.

“First edition of the story of Manon Lescaut and the chevalier des Grieux.”

Manon Lescaut was to occupy a decisive position in the history of the French novel. “A novel as interesting in its adventures as an adventure novel, as moving as a tragedy, as well thought out in its characters as a novel of analysis, realistic in its exact depiction of contemporary customs and in its study of a moral problem which, for more than a century, was to dominate literature, that of the struggle against pleasure and passion.”

According to his habit, Prévost uses a genre that was very popular in the eighteenth century: the fictional memoir. This method of retrospective narration allows the author to multiply the adventures, which each time revolve around a love story ending in the death of the woman. The Histoire du chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut, which is easy to separate from the rest of the Mémoires since it was not lived by the narrator but was reported to him, was immediately so successful that it overshadowed the rest of Prévost’s work.

“All the meaning of the novel, all the fascination it exerts, rests on this particular position of des Grieux : trying to draw Manon into his exaltation of love and obliged to suffer the consequences of his infidelities and his dizzy pursuit of pleasures and money, having sacrificed everything to love, lived as an absolute, and led by this love to compromise himself with prostitution, theft, murder, to deceive his family, to exploit his friends, like Tiberge or M. de T. By calling Prévost’s novel Manon Lescaut, the reader forgets the work of recollection and idealisation carried out by the lover, and retains only the object; what Des Grieux puts at the centre of his life and of his destiny, but remains the most secret, the most irreducibly veiled. The mystery of Manon lies in her place in the novel, since she is seen through the image that des Grieux has and wants to give of her, but it also lies in the impossibility of reconciling her lover’s sentimental expectations with what she can do socially and materially. The paradox of the novel builds on Manon’s character: her lover, in order to bring her into his pathetic narrative and give their love a tragic dimension, has to invoke everything in her behaviour and character that has caused unhappiness, and reveals her indignity and precludes any heroism: her levity, her swindles, her courting, her deportation. Manon is therefore as tragic as she is not: beyond mourning, des Grieux locks himself into a contradiction with no way out, and this is what gives his story its dramatic value. Prévost’s originality lies in having suggested the force of passion by opposing it with tangible, and sometimes grotesque, details: lodgings, a rented carriage, an account of expenses, illicit gains, swindles, a loaded pistol, a forced room, a forgotten panty. But he does not only use material conditions as obstacles to feelings, he makes them part of Des Grieux’s apprehension of love, in his attempt to give it meaning, and to recompose an image of himself and Manon that justifies his conduct and takes the place of what he has lost: they are part of him, and of what he seeks to understand and say about it. This process of integration affects the daily basis of existence, giving the most prosaic elements (a candle, a lock of hair, a gold coin, an inn room) a curious emotional resonance.

This is also true of the circumstantial evocation of the end of the reign of Louis XIV and the beginning of the Regency, with des Grieux’s difficulty in constructing a meaning becoming that of an entire society. A similar contradiction is found in the way in which des Grieux exalts love and ideologically justifies his adventure. He challenges the interdictions that religion, his family or society have opposed to him, and he makes them partly responsible for his misfortune, but in order to grasp his destiny and legitimise his passion, he is forced to borrow the discourses and values from those authorities that condemn him: because of his education, his background, his inclinations, and the very logic of his undertaking, he has no other choice.

What he sees against love and also what he needs to say it, to give beings and feelings a quality and a name: the aristocratic sense of honour that he claims, and that his father invokes against him the religious sense of sin that leads him to distinguish between intention and act, which his friend Tiberge reproaches him for, and his taste for study and literature. Prévost has constantly played with the contradictory nature of feelings, love relationships, moral values and social behaviour, but in Manon Lescaut he has entrusted the expression of these to the main actor, thus drawing from this unresolved tension the principle of a passionate and anxious presence: Des Grieux’s words still resonate with the vibration of desire in the face of what is eluding him. “J.-P. S.

Famous and very beautiful copy, the most precious one cited by Brunet (Sup., II, 293) : “The 7 vols. of 1730-31 were sold for 60 fr. Tross in 18755 ; in mor. by Chambolle, 700 fr. Benzon; in mor. by Hardy, 730 fr. voicin (1876); finally in mor. by Thibaron-Joly, 1200 fr. to the cat. Morgand and Fatout.” The latter being the present copy, 1200 fr. gold! Let us recall that a bibliophile book was then negotiated from 10 fr. gold.

From the library of P. Brunet with ex-libris.