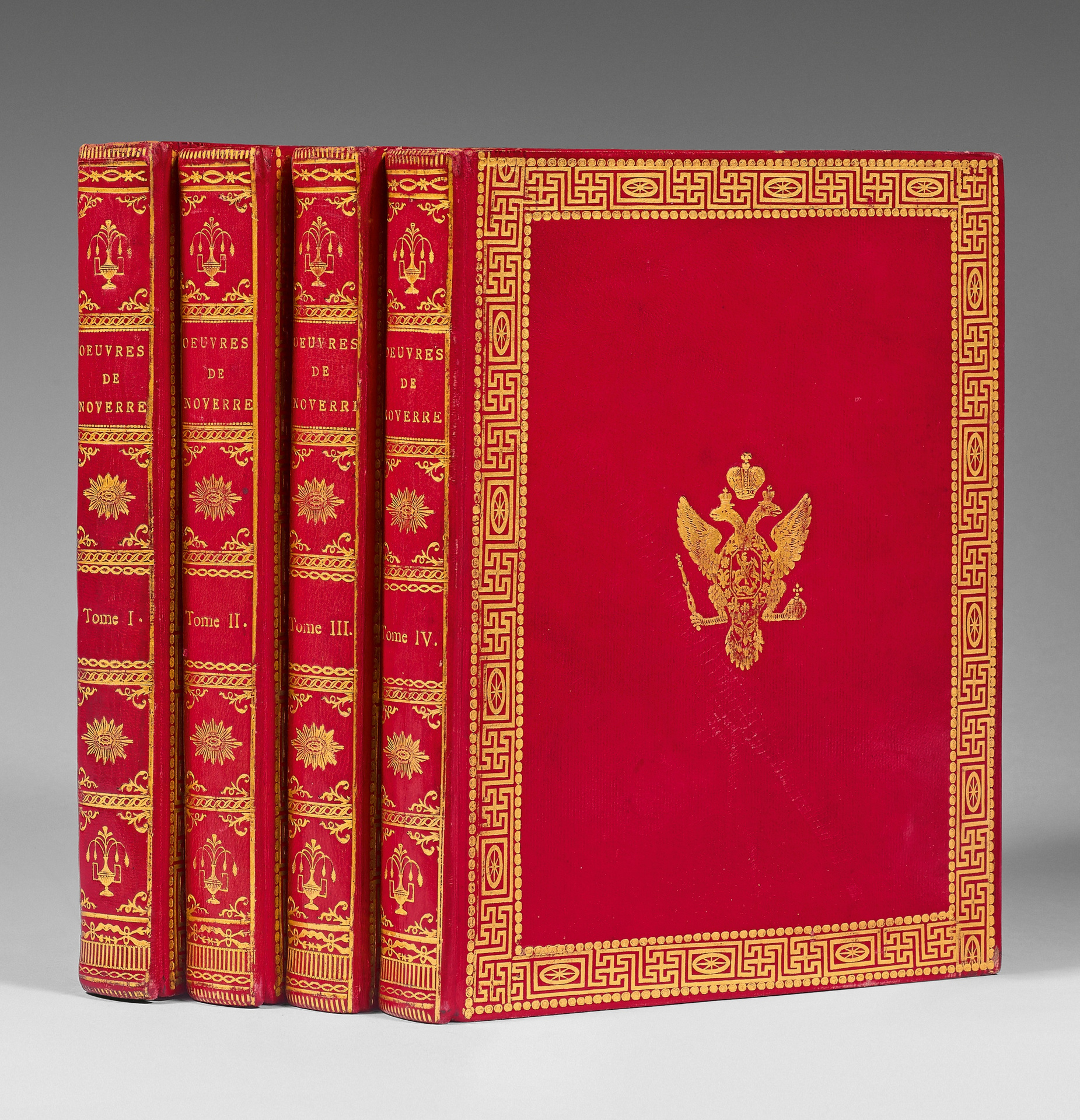

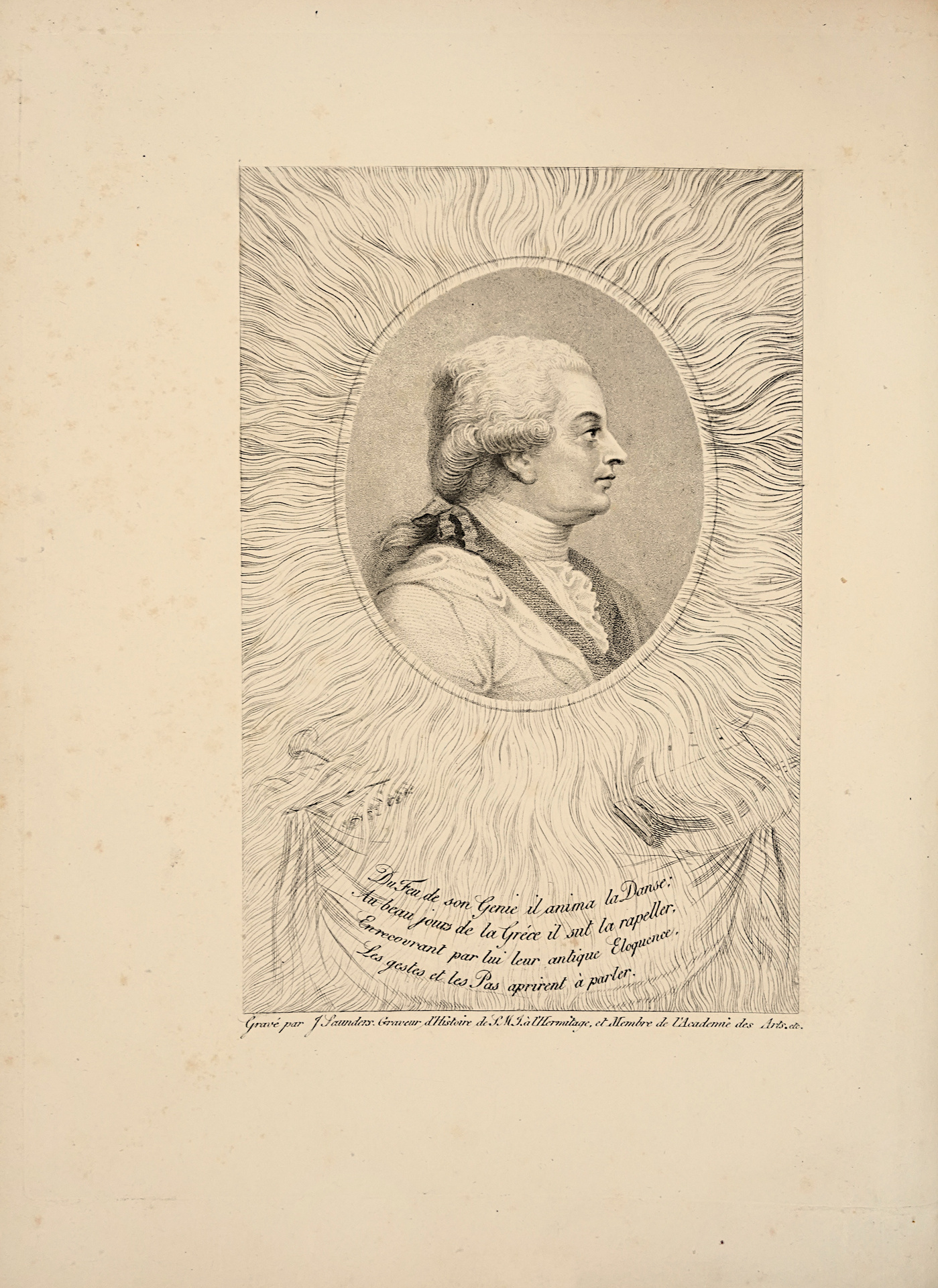

4 4to volumes [253 x 195 mm] of : I/ 1 portrait-frontispiece engraved by J. Saunders, (1) title-lêf, (2) ll., x pp., 240 pp., (1) l. of errata ; II/ (1) f. title-lêf, (1) l. of warning, 240 pp., (1) l. of errata ; III/ 224 pp., (1) l. of errata ; IV/ 256 pp., (1) l. of errata. Contemporary red Russian morocco with gilt with Russian imperial arms, finely decorated flat spines, gilt edges. Contemporary imperial bindings.

Definite edition printed in St Petersburg in 1803-1804 of the famous “Letters on dancing and ballets” by J.G. Noverre.

Born in Paris from a military dad, from Switzerland, Jên Georges Noverre starts as a dancer in Fontaineblêu, in 1742, in front of the court of Louis XIV; he dances in Berlin in front of the court of Frederick the Grêt, then at the Opéra-Comique of Paris (1749), at the Drury Lane of London (1755) and then travels across France. In 1760, he inaugurates his career as a ballet master in the service of the Duke of Wurtemberg (1760-1768), after having published a book on dancing that Voltaire qualified of “genius work”. From 1770 to 1774, he is in Vienna where he collaborates with Gluck, especially to crête the ballets of Iphigenia in Tauris and Alceste. In 1774, he is in Milan, before getting from Marie-Antoinette, his former pupil, the position of chief ballet master at the Royal Academy of Music of Paris (where he replaces Gaétan Vestris in 1776). Among the many ballets he crêtes The Little nothings, for which Mozart had composed a music while he was staying in Paris, stands out. During the Revolution, he goes to England and performs Iphigenia in Aulide at the King’s thêtre of London. Once back to France, he works on a dance dictionary; he will die in Saint-Germain-en-Laye in relative poverty.

“Noverre offers in his writings, especially in Letters on dancing and ballets, an important legacy: filled with 18th century ideology, he elaborates a doctrine and establishes the rules regarding the art of ballet, considered until then as a mere entertainment. He wants to make a true dramatic art of it in agreement with nature and the characters’ manners: he advocates a progressive action, a dance able to express the soul passions and afflictions; he requests a conception unity in the composition of ballet, obliging the composer to adapt his music to the drama and feelings of protagonists. The ballet master must have extensive knowledge in anatomy, music, drawing, painting and a wide humanist culture. Not only must he know dancing, but also to harmoniously coordinate arms, legs and hêd in the movement. He bans pure virtuosity, reforms lêps and insists on the value of placement of dancers. He considerably lightens costumes removing masks, wigs, sack-back gowns. His theories, hardly applied during his lifetime, were taken back afterwards and can be considered as the essential foundations for the 19th and 20th century choreographic art.”

Jane Patrie

A precious dedication copy offered to the Czar Alexander I of Russia (1777-1825) with this dedication:

“TO HIS MAJESTY

EMPEROR OF ALL RUSSIA.

SIR,

The double favor that I have just received from your IMPERIAL MAJESTY has touched my hêrt with the most vivid gratitude. Not only he allows me to dedicate him my work, but he agrees to add to this grace, the one of printing it in my benefit. This honor given to the arts

deserves to be celebrated by all the living artists …”

Magnificent volumes printed in St Petersburg in 1803-1804 bound in contemporary red morocco decorated with the arms of Alexander I of Russia Pavlovich, grêt-son of Catherine the Grêt, emperor of all Russia, coming from the library of Tsarskoe Selo with armorial stamp on êch title-page.

Magriel p. 115; Niles & Leslie p. 389 (“Certainly the most bêutiful and perhaps the most complete of all the editions of Noverre”)