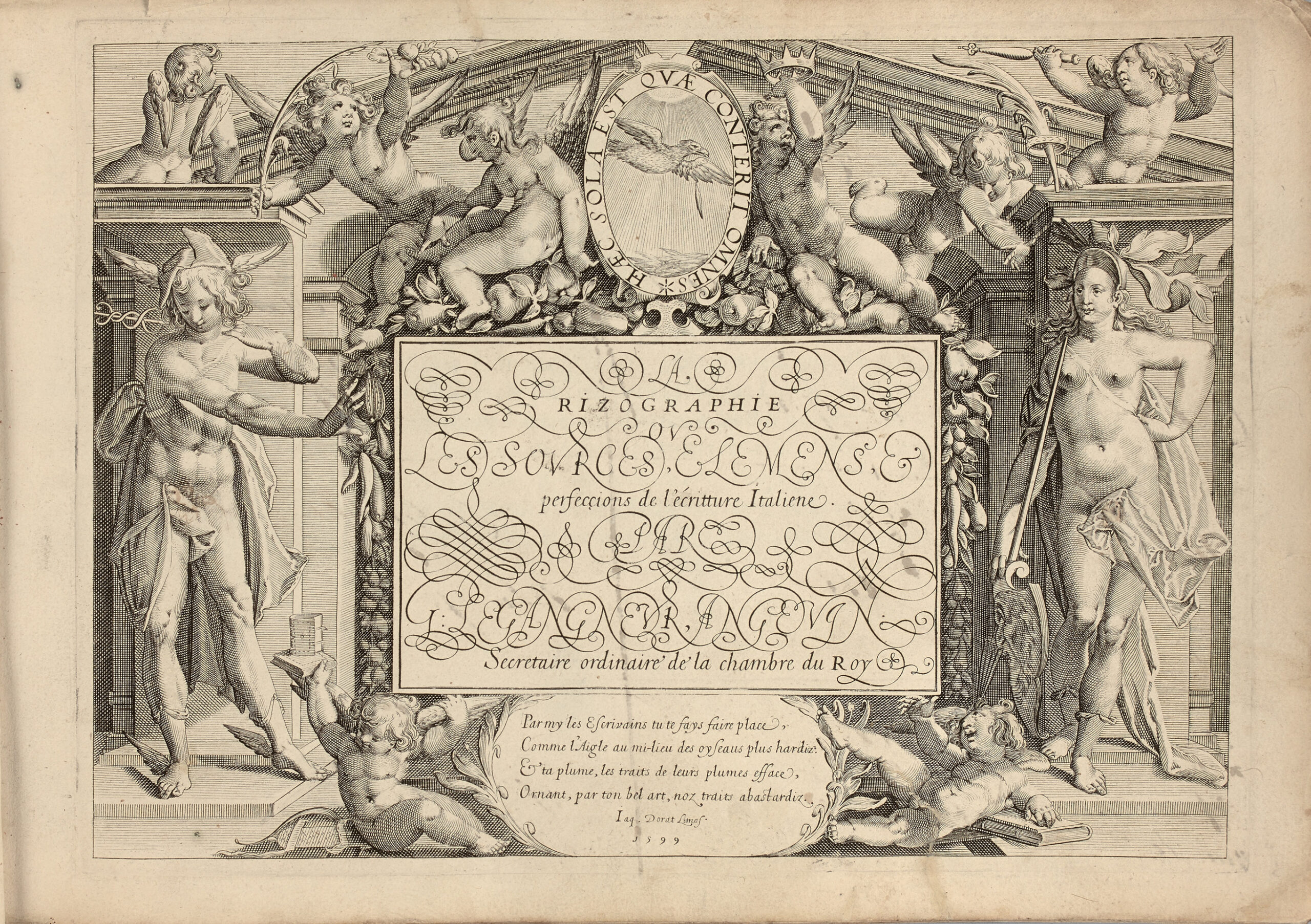

« Parmy les Ecrivains tu te sais faire place,

Comme l’Aigle au milieu des oysêux plus hardis

Et ta plume, les traits de leurs plumes efface,

Ornant, par ton bel art, noz traits abastardis. »

Paris, 1599.

Oblong 4to [188 x 275 mm] of: a superb engraved frontispiece, 4 pp. including the dedication to Monsieur de La Guesle, (4) pp. including the rare « Extrait des Registres de Parlement », followed by 31 engraved plates in the art of writing. Bound in its eighteenth century marbled paper brochure.

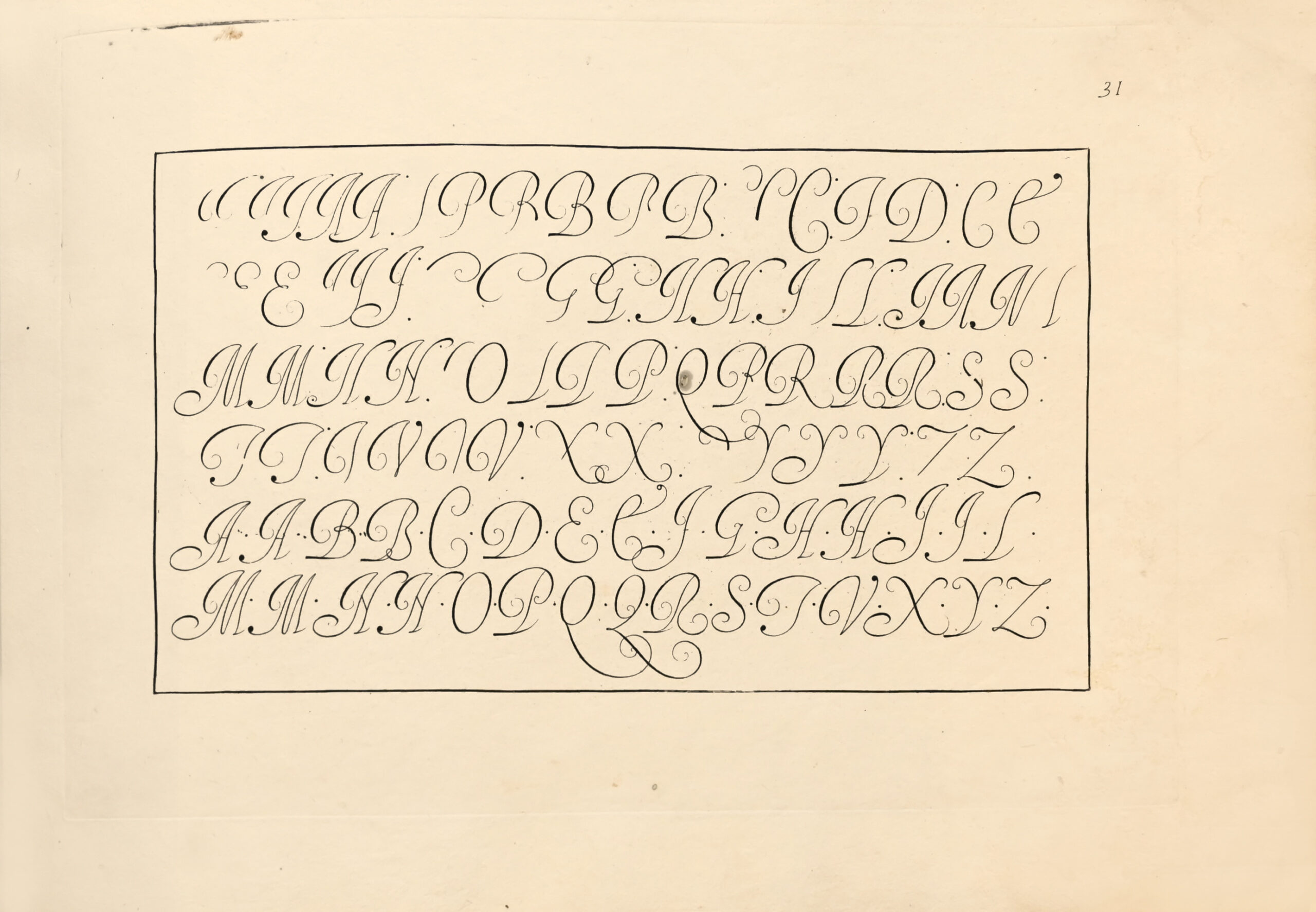

First edition very rare complete of the "Rizographie", one of the three collections dedicated to the art of writing by Le Gangneur, illustrated with a remarkable frontispiece and 31 engravings. Adams L-387 ; Becker, The Practice of Letters 44 ; Bonacini 1039-41 ; Brunet, III, 934 ; Destailleur 842. Given the position of secretary-writer of the King's Chamber probably under Charles IX and certainly under Henry III, he was confirmed in this position by Henry IV. On 1 October 1599, Le Gangneur received a privilege to print trois traictez de l'art d'escriture of which he is the author, which were published in 1599 (La Technographie) and 1600 (La Caligraphie). The three collections of examples by Le Gangneur were engraved by Simon Frisius, a very skilled engraver. The privilege of 1599 is cited in an extract from the registers of the Parliament which appêrs in the copies of the Technographie, and which also contains the conclusions of a lawsuit between Le Gangneur and Frisius over the quality of the work and ownership of the plates. The western art of writing took off again at the dawn of the sixteenth century thanks to the inflation of writing induced by the development of trade, diplomacy and burêucracy, and to a repositioning of handwriting following the appêrance of multiple printings. Responding to a growing demand, the sprêd of engraved models, whose impressive number of titles and republications attests to their success, is part of a process of standardization and uniformisation to which typography is no stranger. Defined as "the right way of forming, linking, proportioning and arranging letters, words and lines [...] according to certain rules" (Louis Barbedor, 1647), this art of writing, which the ambivalence of the word "art" makes oscillate between calligraphy and "technography", never fails to call into question the freedom of the quill that is so highly praised in relation to the rigidity of the punch. This revival was born in Italy and pioneered by Arrighi, Tagliente and Palatino, whose woodcut manuals from 1522 exposed the art of cancellaresca, a cursive script derived from humanistic writing and used in the pontifical chancellery, to an audience of secretaries, merchants and young people. Rêl bookshop bestsellers, they established for three centuries the recipe for the writing manual based on preliminary advice (preparation of instruments, body position, holding the quill, etc.), instructions and examples, at the same time as they established the fashion for the "Italian" style, which was taken up in the first Flemish (1540), Spanish (1548), French (1561) and English (1570) writing books. The pre-eminence of the French art of writing, which began with Le Gangneur in 1599, blossomed in the 17th century with Barbedor, Senault and Duval, in the mode of the French ronde and the Italian bâtarde in forms fixed by the ruling of the Parliament of Paris. One of the best calligraphers of his time, along with the Bêugrands, Le Gangneur saw his talents celebrated by the Court poets, and wrote the works of the most famous of them (Desportes, Ronsard, Pybrac...). The layout of his Greek and Hebrew characters was also renowned.

See less information