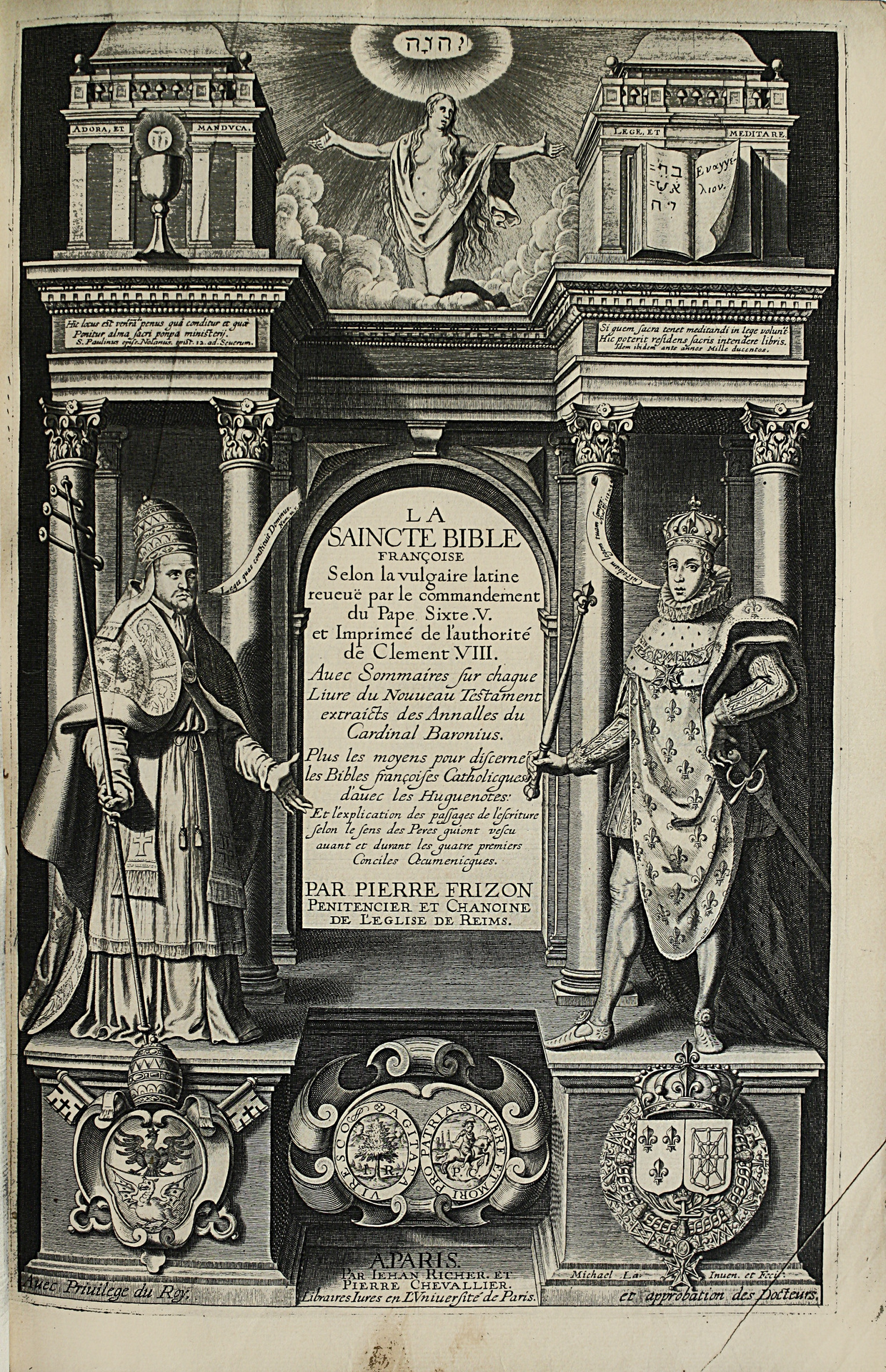

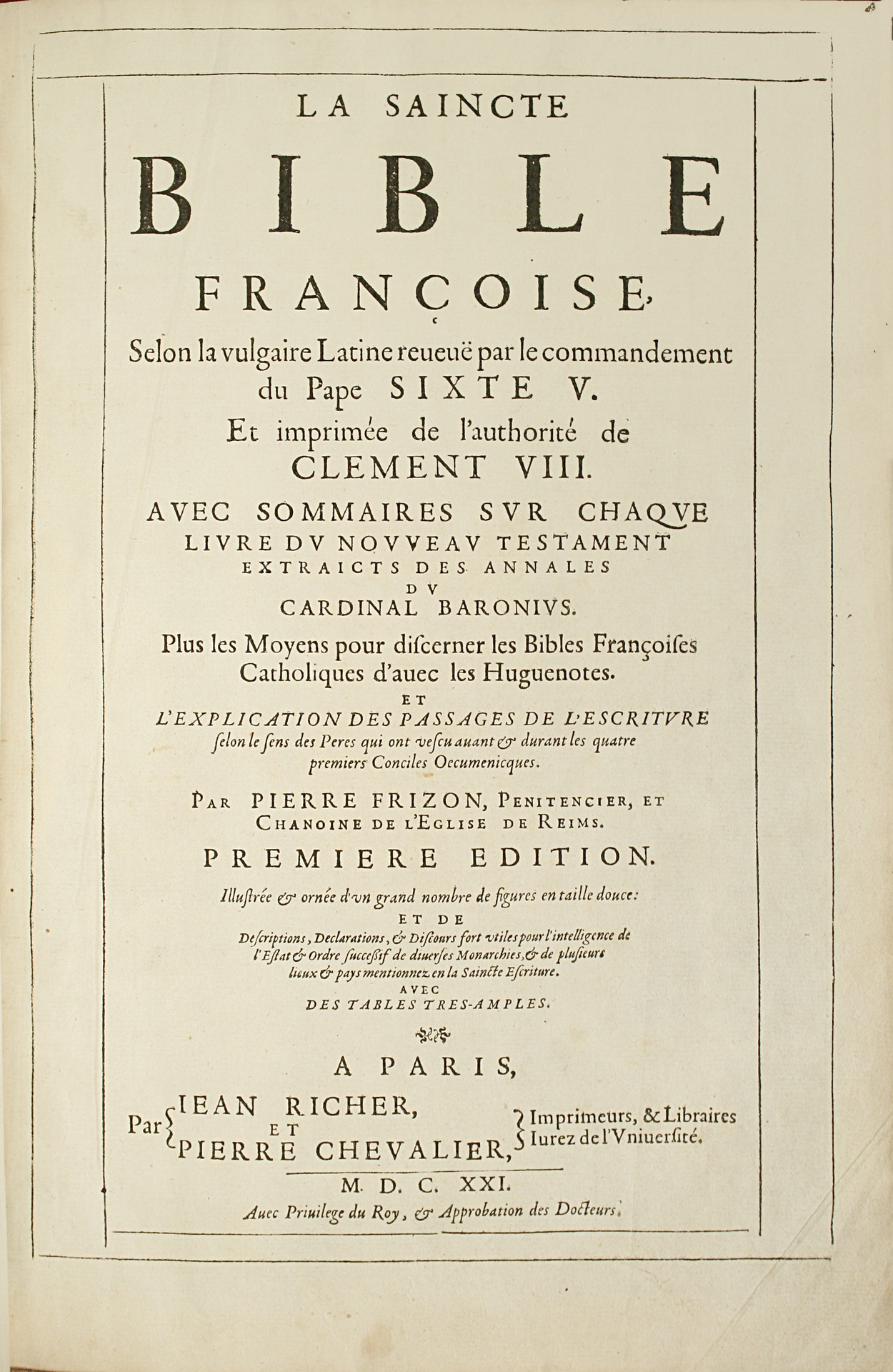

Paris, Jean Richer et Pierre Chevalier, 1621

[Followed by :] – Frizon, Pierre. Moyens pour discerner les bibles françoises catholiques d’avec Les Huguenotes.

Paris, Jean Richer, 1621.

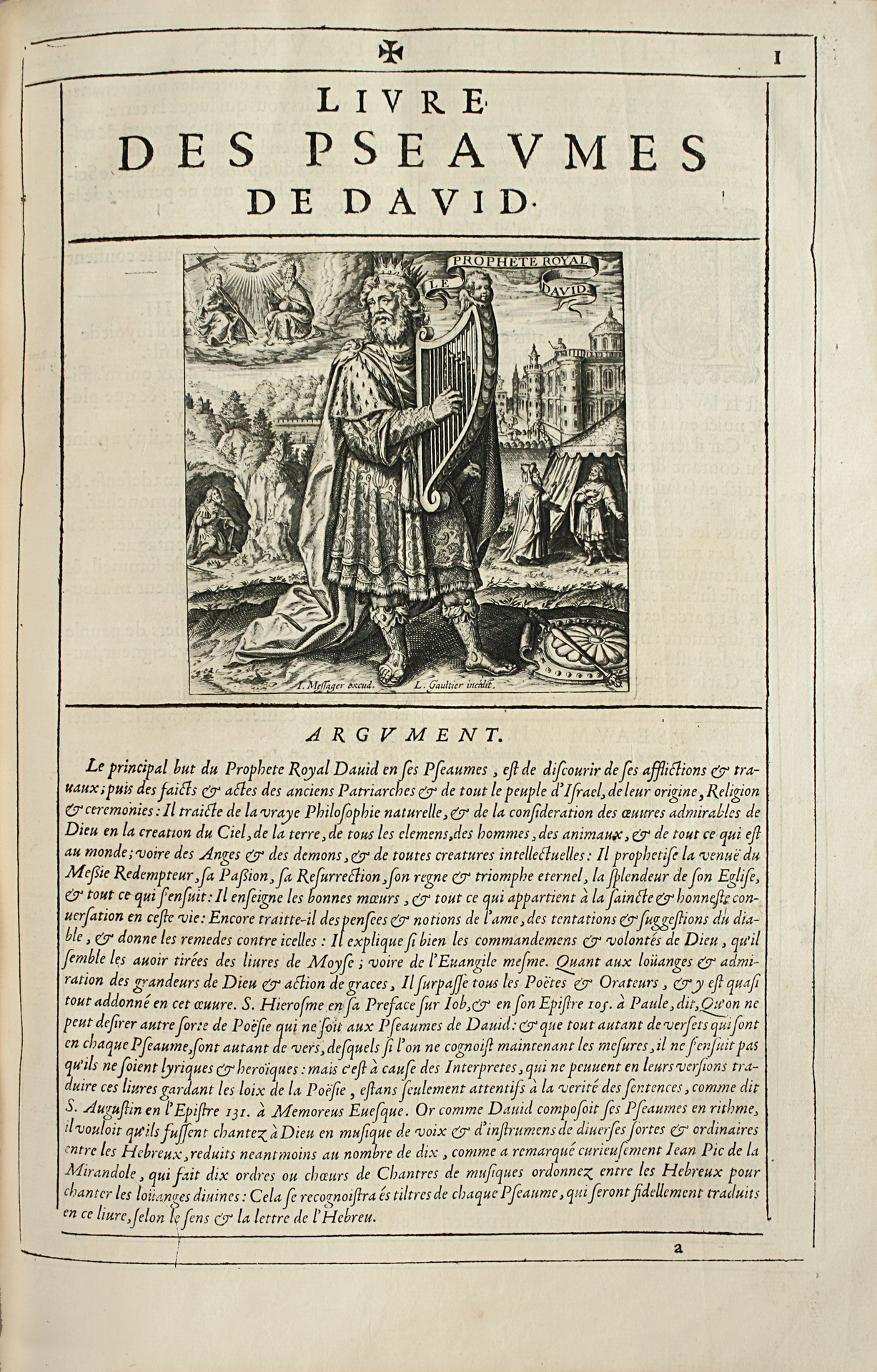

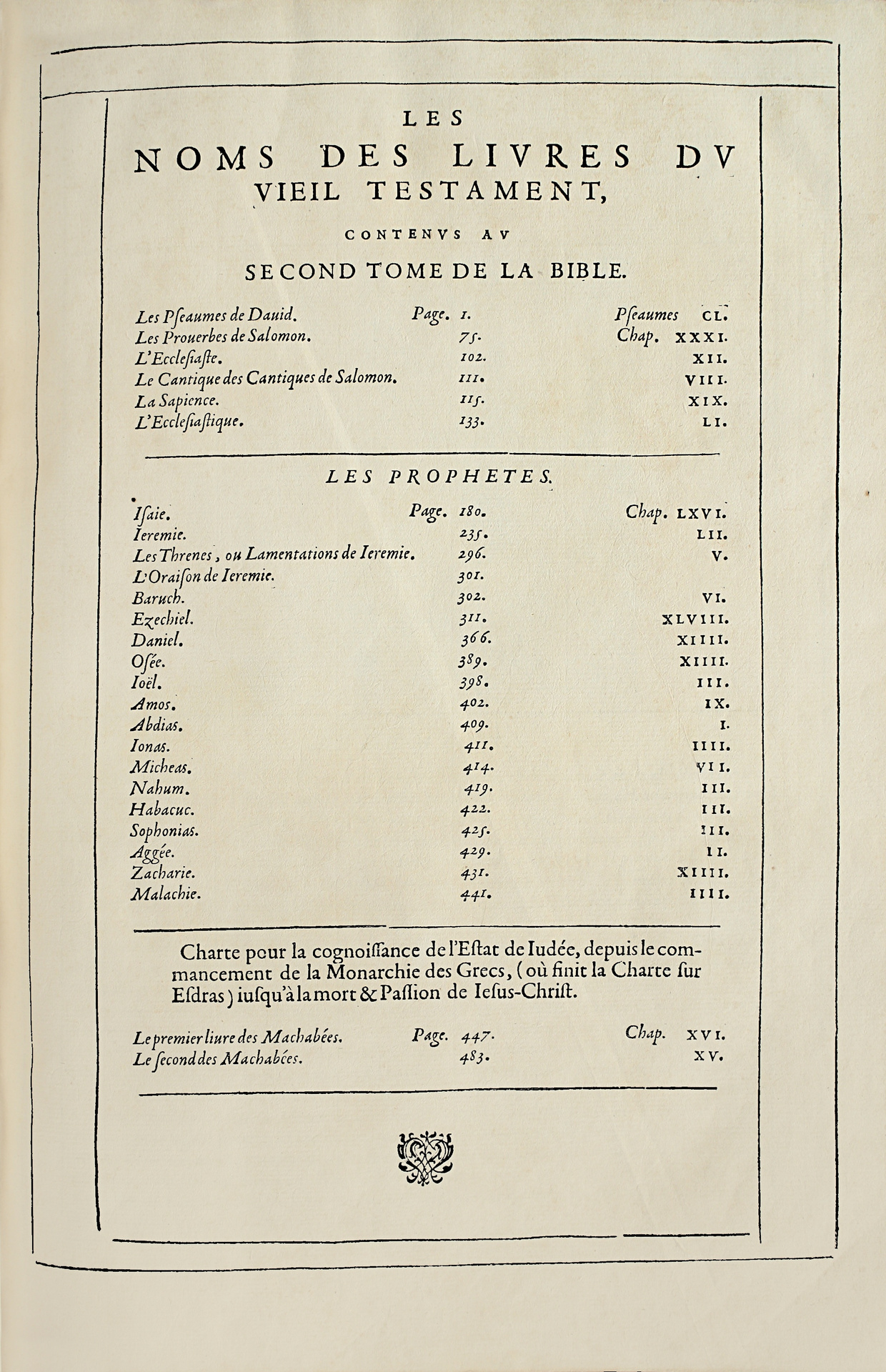

2 parts bound in 3 folio volumes [390 x 260 mm] with 2 columns of : I/ (6) ll. of which 1 frontispiece, 583 pp. 28 engravings in the text; II/ (2) ll. 508 pp. 21 engravings in the text; III/ pp. 509 to 863, 1 l. numbered 864, 3 pp. numbered 510 to 512, 90 pp., (27) ll., 21 engravings in the text, 2 engravings in the title, 1 map. Thus complete.

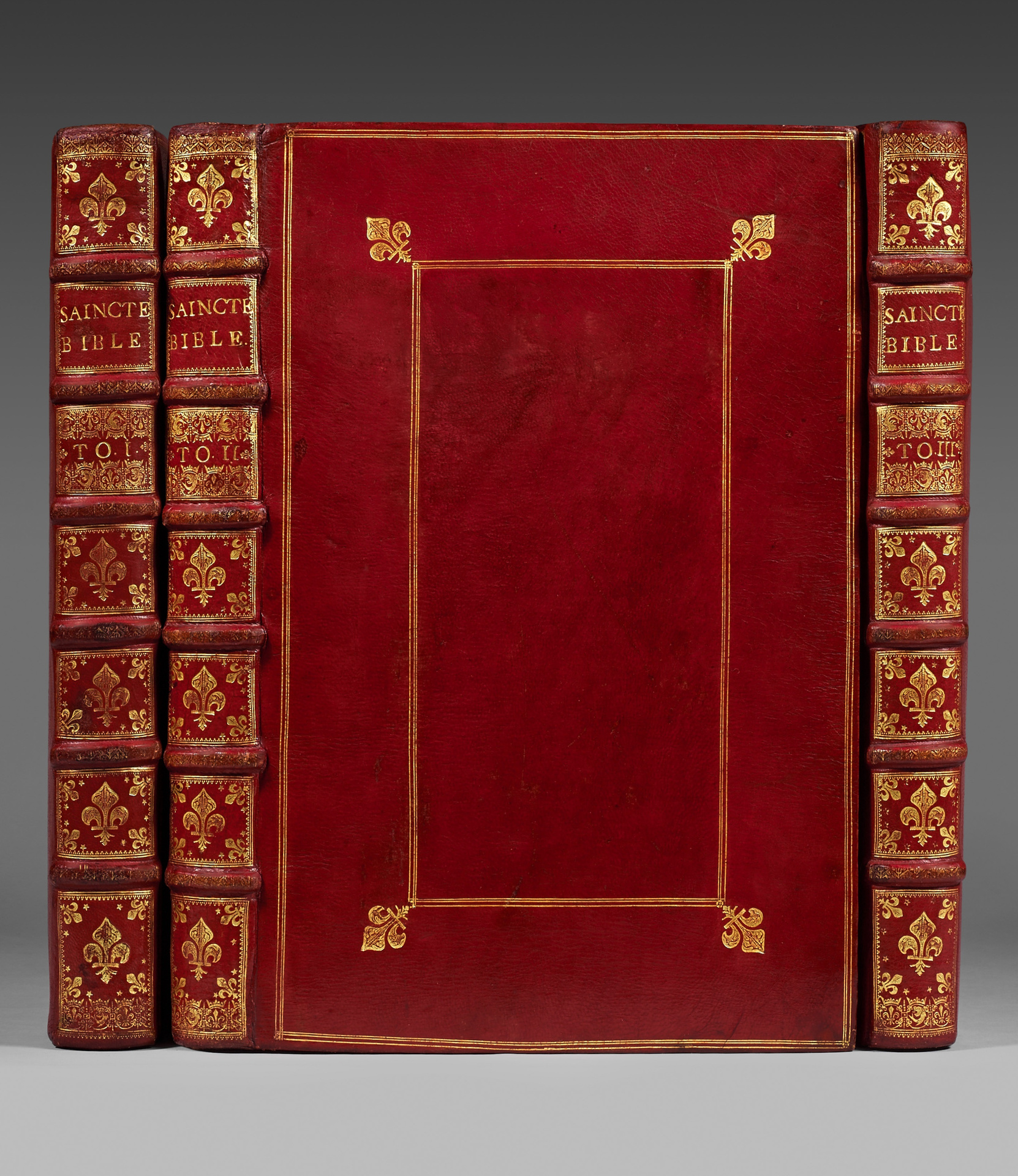

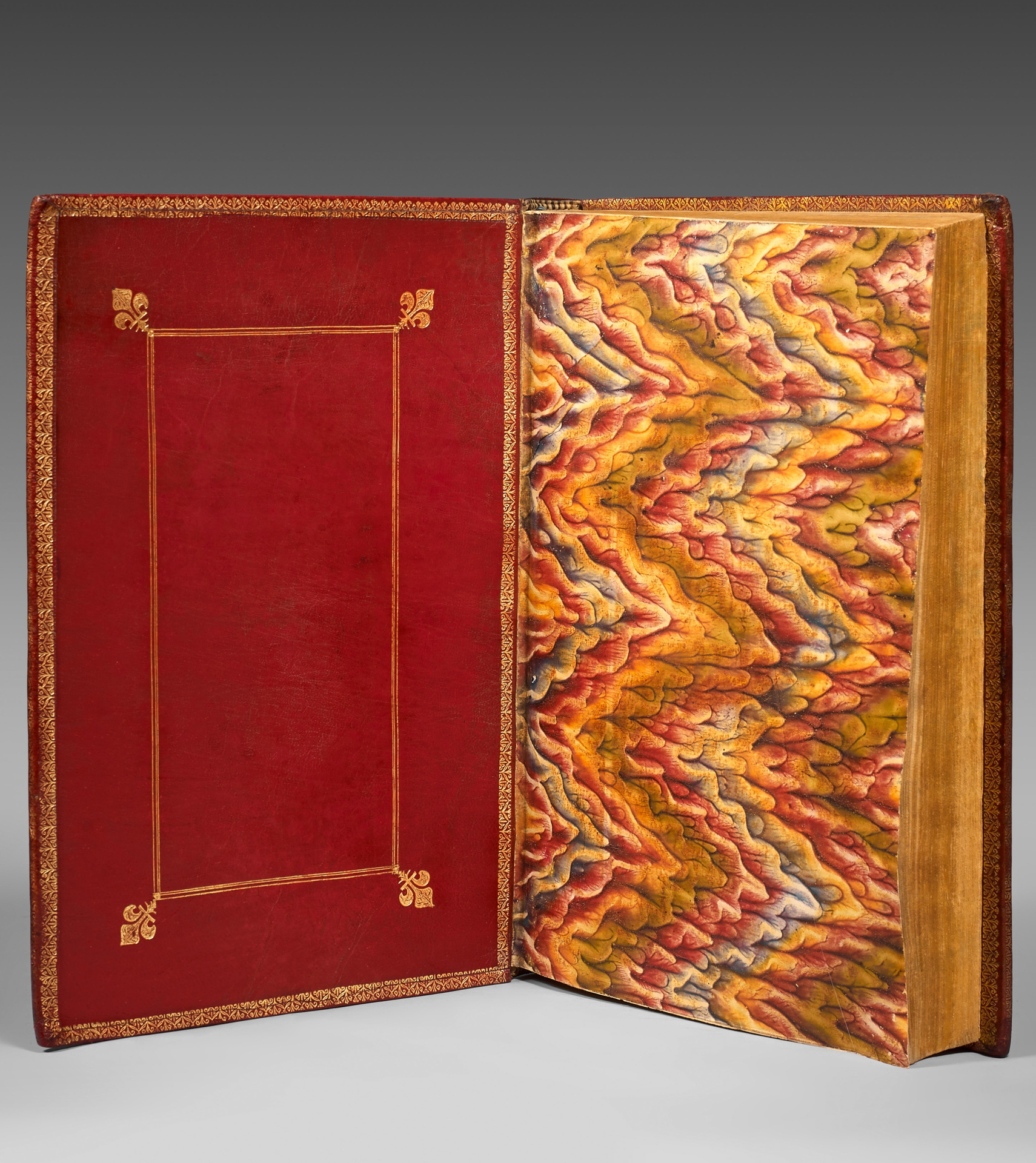

Seventeenth century binding in red morocco; double border of three blind-stamped fillets on the covers with fleurs-de-lys in the corners, spine ribbed decorated with fleur-de-lys, red morocco doublures with gilt dentelle and central frame of three gilt fillets with fleur-de-lys at the corners, marbled paper endleaves, gilt edges. Royal binding made around 1678 in morocco with morocco doublures.

First edition of this famous illustrated French Bible, known as the Frizon Bible, which was censured by the Sorbonne upon publication.

In 1689, La Caille also praised it and Michel de Marolles pointed out the engravings. This edition of the Bible is the first to have been made in Paris; it is very rare, & no examples of it are even known: there are two in Paris; one in the King’s library, the other in that of the Célestins. The printing is very beautiful (G. F. de Bure, Bibliographie instructive, 1763, 1, n°31). – Duportal, Catalogue, 412.

This first edition of this version of the Louvain Bible, still considered too Protestant by the Sorbonne, is the first French Bible illustrated with intaglio engravings.

The work holds the first rank among the illustrious books of the time of Louis XIII, with 70 original etchings comprising more than 900 subjects, plus a frontispiece by Michel Lasne, two vignettes and a map. Alongside anonymous artists, most of the great draughtsmen and engravers of the times contributed to the illustrations of this work: notably Claude Mellan, Michel Lasne, Léonard Gaultier, M. Van Lochom, Melchior Tavernier, Jean Zniarnko, M. Faulte, etc. A major work of biblical publishing, the work is also a masterpiece of French illustration of its time.

“This Frizon Bible of 1621 is decorated with several very beautiful and highly esteemed figures. It is commonly called the Richer Bible, which is sought after by the curious” (Histoire de l’Imprimerie, page 244).

The first Bible printed in French was that of Jean de Rely, which was a revision of that of Des Moulins, printed in 1487 on the orders of Charles V. Naturally this Bible was not a literal version, but a historiated Bible, as it is written on folio 353. One copy is in the bibliothèque Nationale and another in the Arsenal in Paris.

In 1528, Lefèvre d’Étaples finished the entire translation of the Bible, which was printed in Antwerp. Lefèvre’s work was based on the Vulgate (faithfully rendered for the first time in a French translation). It was not intended in itself to become the popular Bible of the French people, but it prepared the way for such a benefit. This work became the model that Protestants and Catholics followed. In 1535, Pierre Robert Olivetan produced a new translation that made up for the weaknesses of Lefèvre’s version. A native of Picardy, he was one of the leaders of the Reformation in France. Because of opposition in France the first edition of this Bible was printed in Neuchâtel (Switzerland), the others in Geneva.

Despite the censorship, many of the Geneva Bibles made it into France. Let us quote a passage from the book “Histoire des protestants en France“, p. 68, which shows the work of some Christians of the time “students and ministers, ball-carriers, basket-carriers, as the people called them, travelled through the country, a stick in the hand, the basket on the back, in the hot and the cold, in the remote paths, through the ravines and the country potholes. They went,” continues Mr de Félicé, “knocking from door to door, often badly received, always threatened with death, and not knowing in the morning where their heads would rest in the evening“.

In 1566, René Benoît published a translation of the Bible, which was censored by the Sorbonne in 1567 and finished publishing in 1568. Benoît had to humble himself before the Sorbonne and admit that his translation was a copy of the Geneva translation, which had to be rejected. The same was true of the revision that Pierre Besse dedicated to Henri IV in 1608, of that of Claude Deville in 1613, and of that of Pierre Frizon dedicated to Louis XIII in 1621.

[Pope] PauI IV ordered that all Bibles in the vulgar language could neither be printed nor kept without permission from the Holy Office. This was in practice the prohibition of reading Bibles in the vulgar language” (Dictionary of Catholic Theology, 15, col. 2738).

The fourth rule of the Index (of forbidden books) published by Pope Pius IV states, “Experience proves that if the reading of the Bible in the vulgar language is indiscriminately permitted, more harm than good will come of it through the temerity of men.”

Pope Sixtus V makes it expressly known that no one may read the Bible in the vulgar language without “special permission from the Apostolic See“.

A wonderful copy bound by Luc-Antoine Boyet, with the characteristic irons (Esmerian, Part II).

The contrast between the haughty elegance of the doublure and covers and the richness of the edges symbolises Boyet’s primacy in the art of French binding in the seventeeth century.

“He was undoubtedly the first bookbinder who took such great care of the body of the work. He excelled in particular in the choice of morocco, the making of the sewing, the endorsement, and the low chases.”

Precious and extraordinary royal copy offered to Louis de France, Dauphin, called Monseigneur and known as Le Grand Dauphin, eldest son of Louis XIV and Marie-Thérèse of Austria, born in Fontainebleau on November 1, 1661.

Each of the three volumes has on the tail of the spine and on the volume number label the mark reproduced by Olivier-Hermal (Manuel de l’amateur de reliures armoriées françaises, Paris 1934, pl. 2522, iron no. 17), the undisputed reference in the field, thus analysed:

“We believe that this iron (associating a fleur-de-lys and a dolphin, both surmounted by the crown of the princes of the blood) must primarily have been uses on volumes designed for the Grand Dauphin (from the year 1678) and that afterwards, it was very often used as a simple ornamentation on numerous bindings, covered with both morocco and calf.” This analysis was confirmed by Jean Toulet, the former chief curator of the B.n.F. reserve.

Some contemporary clerics dispute this attribution and are ignorant of the heraldic science of the classical age. No heraldic iron, to our knowledge, comprising several royal emblems was created in the seventeeth century with a merely ornamental purpose. This armorial iron, composed of a crowned fleur-de-lys and the emblem of the dauphin surmounted by the crown of the princes of the blood, was “used as 1678 on volumes destined for the adolescent Grand Dauphin” and it was only afterwards, with the dauphin major using the coat of arms reproduced by Olivier, plate 2522, that this iron no. 17 “was very often used as a simple ornamentation on numerous bindings, covered with morocco as well as with calf” (Olivier-Hermal). This heraldic nuance, which is certainly far from our modern concerns, apparently escaped the sagacity of certain contemporary enthusiasts, leading them to reject the princely affiliation of all the volumes stamped with heraldic iron no. 17.

It is heraldic heresy to imagine that in the Century of Louis XIV such a royal heraldic iron could originally have been pushed onto books merely as an ornament.

Mr. J. – P. – A. Madden was the first to devote a historical study to this heraldic iron. (See “The Book, Year 1880″).

At the end of a documented and authoritative analysis, he concluded that this iron “was found stamped on the spine of numerous volumes addressed to the Dauphin and printed from 1678 to 1706, i.e. from his seventeenth to his forty-fifth year“.

Half a century later, in 1934, Olivier-Hermal confirmed the use of this heraldic iron, reserving it for the first years of its appearance (from 1678). “We have encountered this iron no. 17 on volumes whose publication date is sometimes earlier, sometimes later than the death of the Grand Dauphin (1711). We believe that this iron must have been originally struck on volumes intended for the Grand Dauphin, and that it was then very often used as a simple ornamentation on numerous bindings, covered with both morocco and calfskin.” (Olivier-Hermal).

Jean Toulet, former Chief Curator of the Reserve des livres rares at the B.n.F. and an undisputed authority on the classical period, considers that the very rare volumes from the end of the 17th century contemporary bound in morocco with morocco doublures decorated with a single fleur-de-lis were indeed intended for the royal princes.

The sumptuous bindings of this bible, censored by the Sorbonne, decorated with extreme elegance, are the work of the workshop of Luc-Antoine Boyet.

Boyet was working for the Grand Dauphin at the time and “the practice of good aristocratic taste at the end of the seventeeth century was to minimise as much as possible the mark of belonging and the size of the coats of arms adorning the bindings.”

Louis de France, called Monseigneur, or the Grand Dauphin, received the cross and cordon of the Order of the Holy Spirit at birth; his governor was the Duke of Montausier and his tutor Bossuet. He married Marie-Anne-Christine-Victoire de Bavière on 7 March 1680, in Châlons-sur-Marne, who died in 1690, and gave him three sons. Received as a knight of the Holy Spirit on 1 January 1682, he campaigned for some time in Germany and Flanders (1688-1694), but was constantly kept out of business by Louis IV. The Grand Dauphin secretly married Marie-Émilie Joly de Choin around 1695. He died on 14 April 1711, of smallpox, at the Château of Meudon

This prestigious copy was catalogued and reproduced in colour 20 years ago by Pierre Beres at a price of 450,000 ff (70,000 €) “Livres et Manuscrits significatifs et choisis, N°25″.

Pierre Berès catalogued the 1544 first edition of Maurice Scève’s “Délie” at 275,000 FF, the 1556 Œuvres de Rabelais at 300,000 FF, and the famous 1555 first edition of Louise Labé Lionnaize’s Œuvres in contemporary vellum at 675,000 FF (≈ 100,000 €). This volume is now valued at more than €650,000, and a copy was recently sold in New York in a modern binding for €450,000 to a European bibliophile.