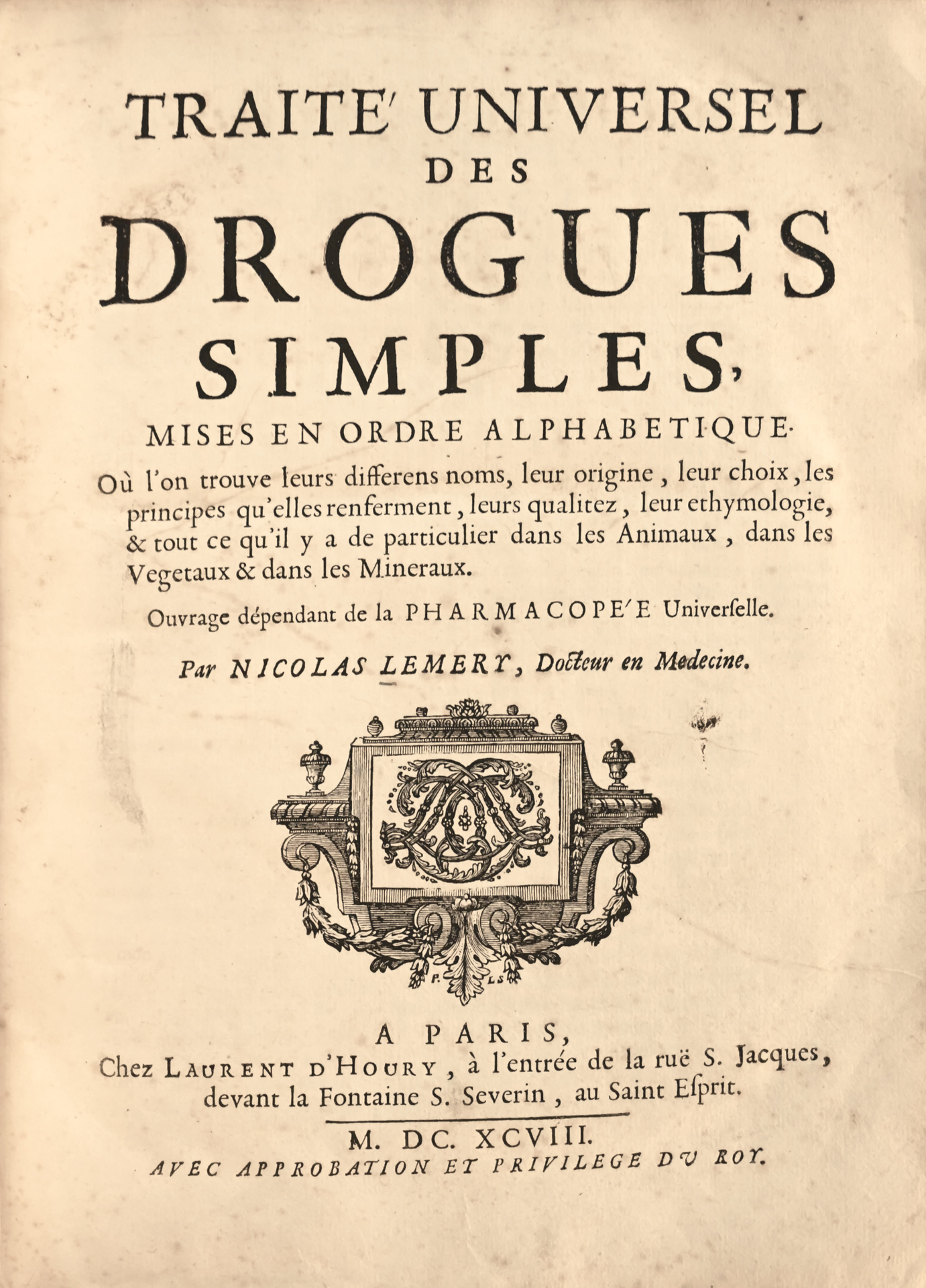

Paris, Laurent d’Houry, 1698.

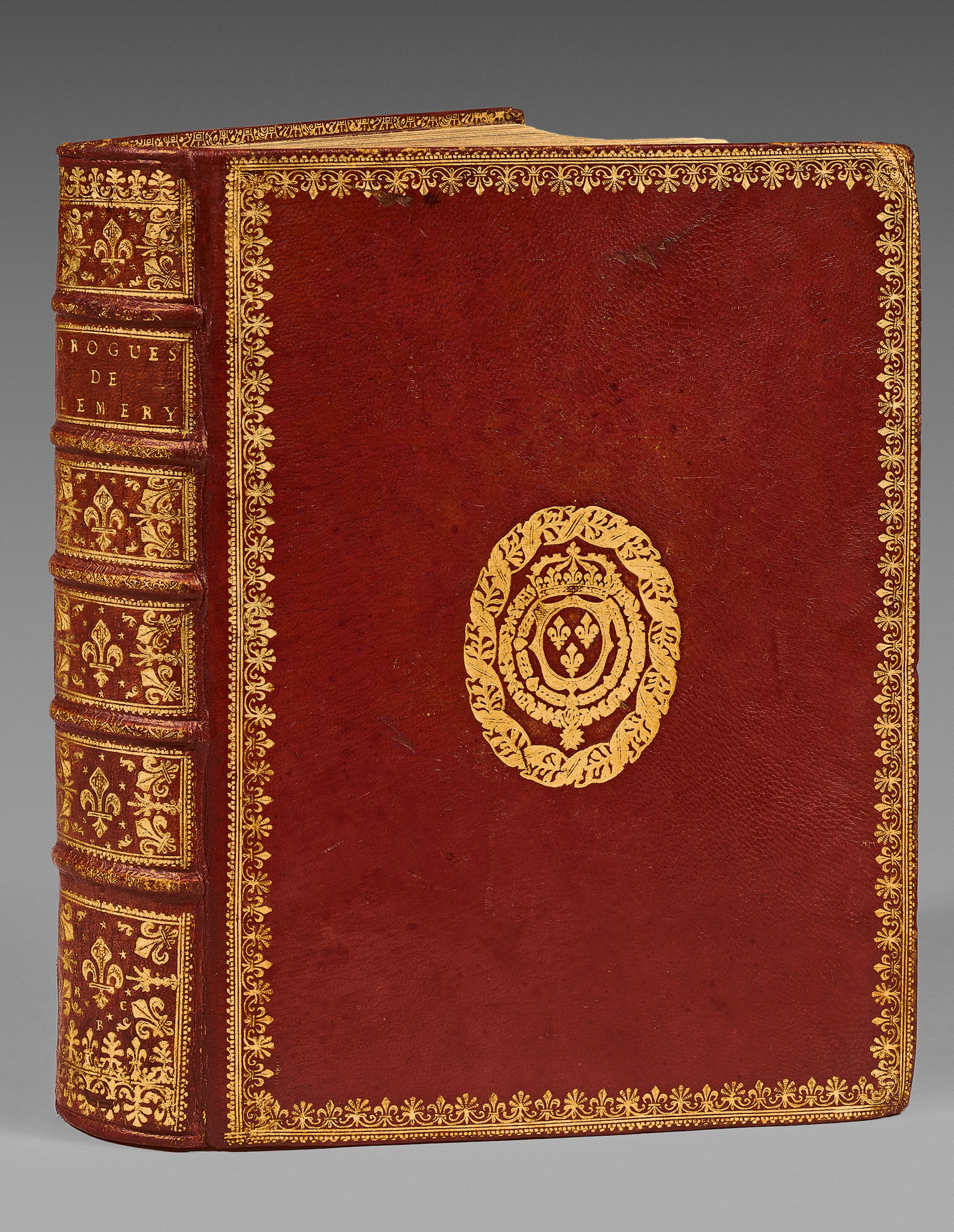

4to [254 x 185 mm] of (8) ll., 838 pp., (31) , red morocco, covers decorated with fleur-de-lys garland, arms in the center, spine ribbed decorated with some large gilt fleur-de-lys, RBC letters at foot, inner scroll and gilt edges. Contemporary binding.

First edition of one of the most important books for the knowledge of plants and their therapeutic virtues.

Rahir, La Bibliothèque de l’amateur, 505.

It was, together with Pomet’s Histoire des drogues, the reference in this field for almost a hundred years.

Lémery published a first edition of the Cours de chymie in 1675, which was constantly republished throughout his life and even after his death until 1757, and translated into English, German, Italian, Spanish and Latin. A skilful experimenter, he presented all the empirical knowledge of late 17th-century chemistry in nearly a thousand pages in the latest editions. The Cours de chymie is the culmination of a literary genre, known as “chemistry courses“, which developed in France after the success of Jean Béguin’s Tyrocinium chymicum at the beginning of the century.

Lémery circumvented the shortcomings of chemical analysis by proposing a corpuscular and mechanistic model known as the point-and-pore model, which was admittedly very limited in application but which, combined with precise weighing of the reagents, allowed a more accurate representation of a chemical reaction, a concept that was still in the making but not yet fully achieved.

Although his Cours de Chymie was authoritative for a century, his other publications were no less successful during the age of Lumières.

Lémery gave demonstrations in his laboratory (first installed in the hotel of the Prince de Condé, in the Odéon district), which were very popular with scientists and people of the world. The Grand Condé himself and Bourdelot, the future physician of Christine of Sweden, attended. According to Fontenelle, the ladies themselves, drawn by fashion, flocked to the event.

Lemery was a Protestant and the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1685) forced him to sell all his offices, forbidding him to teach and practice chemistry, medicine and pharmacy. Driven to ruin, he finally abjured.

Louis XIV, recognising his talents and wanting to make him a shining example of a return to Catholicism, granted him new letters patent and imposed their acceptance on his confreres.

“Nicolas Lémery (1645-1715) was “the first reasonable chemist”, to reduce it to clearer and simpler ideas, to abolish the useless barbarity of its language, to promise on its part only what it could and what he knew it was capable of executing, and from this came the great success. In 1675 he published his ‘Cours de chimie’. It was translated into Latin, German, English and Spanish. The author was called the ‘Great Lémery’. However, so many services rendered to science did not protect him from persecution. In 1681, Lémery’s life began to be greatly disturbed because of his religion. He was ordered to resign from his position within a specified time […]’. This is Fontenelle’s account.

He thought he would be more secure in the shelter of his status as a doctor of medicine. At the end of 1683, he took the bonnet at the University of Caen. But the Edict of Nantes having been revoked in 1685, the practice of medicine was forbidden to the so-called Reformed. Lémery was left without a position and without resources. He was forced to convert in August 1686 and resumed the practice of medicine in his own right […] ‘Almost all of Europe,’ says Fontenelle, ‘learned chemistry from him, and most of the great chemists, both French and foreign, paid him tribute with their knowledge’.

The ‘Traité des drogues’ shows, according to M. Dumas, an observer of consummate skill. (La France protestante, VI, p. 543)

Precious copy of Louis XIV bound in red morocco with his arms and perfectly preserved. At the bottom of the spine, initials of the bookbinder of the king’s library.

It then belonged to Pierre Perrinet de Faugnes (1715-1773; heraldic bookplate), a very prosperous financier from an important family of financiers and farmers-general. His daughter married in 1775 the son of Mme d’Houdetot, née Lalive (another line of farmer-generals) – for whom Rousseau felt a passionate but unrequited love (‘We were both drunk with love, she for her lover -Saint-Lambert-, I for her’, he notes in the Confessions).