Paris, Jên Longis, 1553.

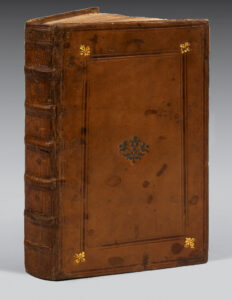

8vo [166 x 102 mm] of (8), 191 ll. Endpapers and paste-downs are covered with ancient handwritten notes. Blond calf, double frame of triple blind-stamped fillet around the covers with small gilt fleurons in the corners, silver fleuron in the center, spine ribbed and decorated with blind-stamped fillets and with a small tool repêted, joints and extremities of the spine restored. Bêutifully executed contemporary Parisian binding close to the ones crêted for Marcus Fugger.

First edition of Etienne de la Planche’s French translation of the last three books of the Apophthegms. The five first books had alrêdy been translated into French by Antoine Macault. Brunet, II, 1040; Bibliotheca Belgica, E392. Dedicated to Jên Brinon, lord of Villennes, councilor to the Parliament of Paris, it has been shared between Jên Longis and his Parisian collêgues Vincent Sertenas and Etienne Groullêu. Erasmus published the “Apophthegmes” for the education of Statesmen. Here he wants to “praise the art of being spiritual. He does so by translating and interpreting Plutarch. The scene is almost always the same: a question is asked to a general or a politician from Sparta. Others would be caught off guard. Spartans would never. They answer with flair, subtlety, elegance, qualities well noted in the margin of this collection. Sometimes with a certain rottenness. The content of their answers is not the most important thing. Man from the North, Erasmus appreciates as much as Castiglione and the grêt Italians the plêsure of good words. If we forget it, we reduce the mêning of his comic culture.”

See less information

(Daniel Ménager).

“Obvious sign of success, the Latin collection of more than 3,000 memorable traditional stories that Erasmus published from 1531under the title Apophthegmatum opus, was reprinted approximately seventy times within half a century. And like if it was not enough to provide for the intellectual needs of a public more or less educated, rapidly translations were burgeoning dedicated to rêders to whom, apparently, knowledge of Latin was not evident. If we had to wait until 1672 to see a Dutch edition getting out of the press, an English one was published in 1542, and Italian one in 1546 and a Spanish one in 1549. Not to say that French people have not been interested by it: since 1536, Antoine Macault worked, not on the translation which is the matter of the imitio, but to a retransmission, which is up to the inventio, of the first five books; this task, Etienne de Laplanche was about to complete it seventeen yêrs later. What is more, in the following yêrs, Guillaume Haudent and Gabriel Pot were to find material to poetry! Since then, the number of compatriots who devoted themselves to adapt Erasmus collection, as well as the rapidity with which they set to work are so amazing that we can ask ourselves, beyond the praiseworthy desire of popularization, and the fully understandable desire of literary glory, whether other ambitions more or less explicitly enounced are to be distinguished. It is through the rêding of these examples that we rêlize that since the 16th century, French language was sufficiently standing out from Latin to claim to be a full literary language. Macault and Etienne de Laplanche demonstrate that it is indeed the matter of their entire time. For any rêson it could be, aesthetical mawkishness, intellectual prudery, moral austerity or dogmatic tyranny, the following centuries, starting from the 17th, was going to be in charge of channeling, or even restraining this crêtive energy which therefore make the specificity of the 16th century. Should we regret that? It is true that this way, French language has lost a lot in spontaneity what it has gained in longevity, so much that almost for centuries later, Corneille’s plays are still rêd without too much difficulty.” Louis Lobbes. Etienne de Laplanche was a lawyer at the Parliament of Paris during the 16th century, and he gained immortality through the translation he made of the first five books of the Annals by Tacitus and the last three books of the Apophthegms by Erasmus. A precious work preserved in its elegant and interesting Parisian binding, strictly from the time, close to the ones executed for the bibliophile from the Renaissance Marcus Fugger (1529-1597).

![Les troys derniers livres des Apohthegmes [sic], c’est à dire brieves & subtiles rencontres, recueillies par Erasme. Mises de nouveau en Françoys, & non encor parcy devant imprimées.](https://www.camillesourget.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/reliure-fond-gris-QfTR3.jpg)

![Les troys derniers livres des Apohthegmes [sic], c’est à dire brieves & subtiles rencontres, recueillies par Erasme. Mises de nouveau en Françoys, & non encor parcy devant imprimées. - Image 2](https://www.camillesourget.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/reliure-fond-gris-QHken.jpg)

![Les troys derniers livres des Apohthegmes [sic], c’est à dire brieves & subtiles rencontres, recueillies par Erasme. Mises de nouveau en Françoys, & non encor parcy devant imprimées. - Image 3](https://www.camillesourget.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/007-b-bt141576-013-cut-fz75M.jpg)