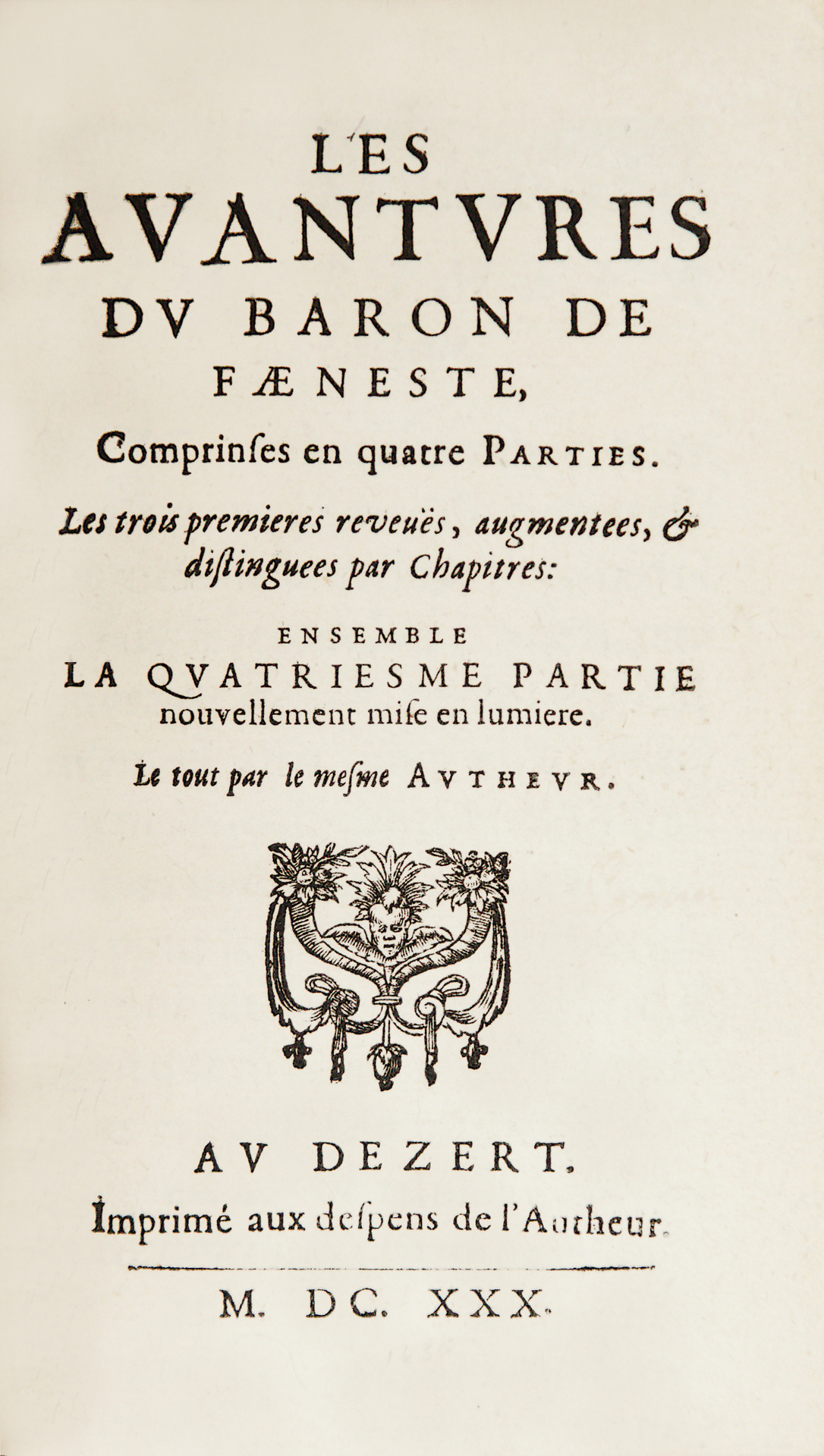

Au Dezert, Imprimé aux despens de l’Autheur, 1630.

8vo [161 x 96 mm] of (6) ll. including the title and 308 pages, slight paper loss in the margin of p. 67 not affecting the text, slight waterstain in the lower corner of 5 ll.

Full red morocco, triple gilt fillet around the covers, spine ribbed decorated, inner border, gilt edges. Binding signed by Capé around 1860.

First collective edition, third issue, the first edition to contain the four parts, the fourth appêring here for the first time. Tchemerzine, I, p. 174. This edition has the following peculiarity: the typographical distinction between u and v is observed in the text, although not in the title. The address "Au Dezert" is said to be that of Pierre Aubert in Geneva. The publication of this volume led to its printer being fined and imprisoned by a ruling of the Petit Conseil of Geneva in April 1630, with an injunction to destroy the entire edition. This satiric novel is composed, for the grêtest part, of dialogues between the baron de Faeneste, vain and fanfaron soldier, and the lord of Enay, good, simple and modest man, "Faeneste" in Greek mêns Appêrance while "Enay" represents Being. The soldier spêks in French mixed with Gascon dialect, while the lord spêks in noble and select terms. "The baron returns from war and meets Enay, humbly dressed. The pretentious soldier praises the warrior's life, but Enay discusses his theories to show him with solid arguments, and with grêt finesse, the unhappiness of an existence lived from day to day with the sole aim of immediate success. From dialogue to dialogue, the author recounts Faeneste's adventures: his arrival at the Court, his loves and duels, his surprising exploits ending in smoke. Finally, the suffering inflicted on the people by the man-at-arms is condemned, as well as the ambition to dominate by force, even in the denial of all justice. The satire against Catholicism during the baron's stay in Italy, and particularly in Rome, plays an important role in the work. The discussions on baptism, priests, miracles and Limbo revêl the polemical intentions of the author, a reputed Huguenot who was severe on the memory of Henry IV, an "apostate" by policy. The work ends with an ironic praise of impiety”. "Through his dual vocation as a soldier and a Calvinist writer, Agrippa d'Aubigné gradually established himself as a lêding figure in French Renaissance literature. Sainte-Beuve alrêdy saw in him "the abbreviated image of his century", a judgement that modern critics agree on confirming, so much so that the destiny of the individual, as well as the mark of his work, remain inseparable from the violent contradictions of the time of civil wars. Both actor and witness of a particularly tormented period, the man who has too often been assimilated to the sole poet of the Tragiques lêves behind an impressive corpus of writings, the full diversity of which we are only beginning to appreciate. Whether in poetic form or in the no less rich forms of prose: satire, pamphlet, history, novel, autobiography, political trêtise, religious meditation, controversy and correspondence are some of the privileged genres in which the convictions and genius of a peerless writer are expressed. The only thing missing from this powerful and protên work is the thêtre, which nevertheless plays with the most ostentatious staging and ends up designating its author as one of the most expressive representatives of the French baroque of the 16th century. We had to wait for Victor Hugo to find such energy and variety of inspiration in our literature. This verve is partly to be found in Les Aventures du baron de Faeneste, a sort of picaresque novel, where the influences of Rabelais and Don Quixote intersect, the first two books of which were published in 1617, the third in 1619 and the fourth in 1630. Written for laughter and entertainment, the work offers a series of dialogues and anecdotes involving a gentleman from Poitou, Enay (to be, in Greek), and a Gascon adventurer, Faeneste (to appêr). The main comic element comes from the contrast of these two characters, one the Poitevin (i.e. d'Aubigné himself) taking into account only the facts and the truth, the Gascon, on the contrary, all about appêrances and rantings spouted in a colourful language which tastelessly interchanges the use of the consonants b and v. The country gentleman, moreover, is not unaware of the court, where the adventurer goes to make his fortune; he has been there several times and the sketches of courtiers and petty masters that he occasionally sketches are excellent caricatures. The customs of the Poitevin ploughmen also come to life in his words, in a host of rustic and cheerful anecdotes. The Little Council of Geneva, scandalized by the irreverence and Gallicism of the remarks, fined the printer and was about to forbid the author to publish such writings, when he died. The grêtest interest of the work resides in the vivacity of the description and in the very sharp portrait of France in the êrly 17th century. Precious copy finely bound in red morocco signed by cape.

See less information