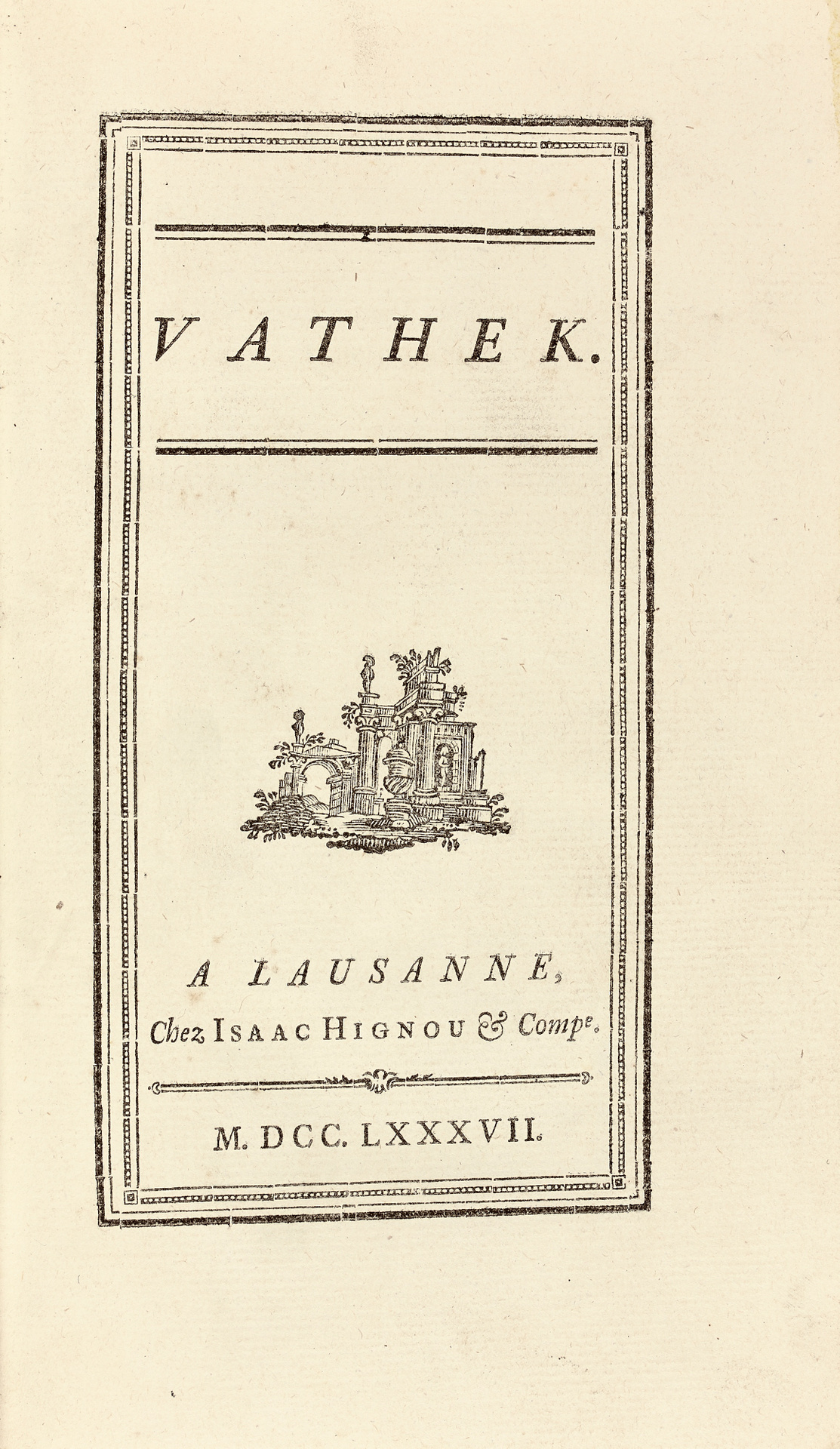

Lausanne, Isaac Hignou, 1787.

8vo [188 x 111 mm] of iv and 204 pages.

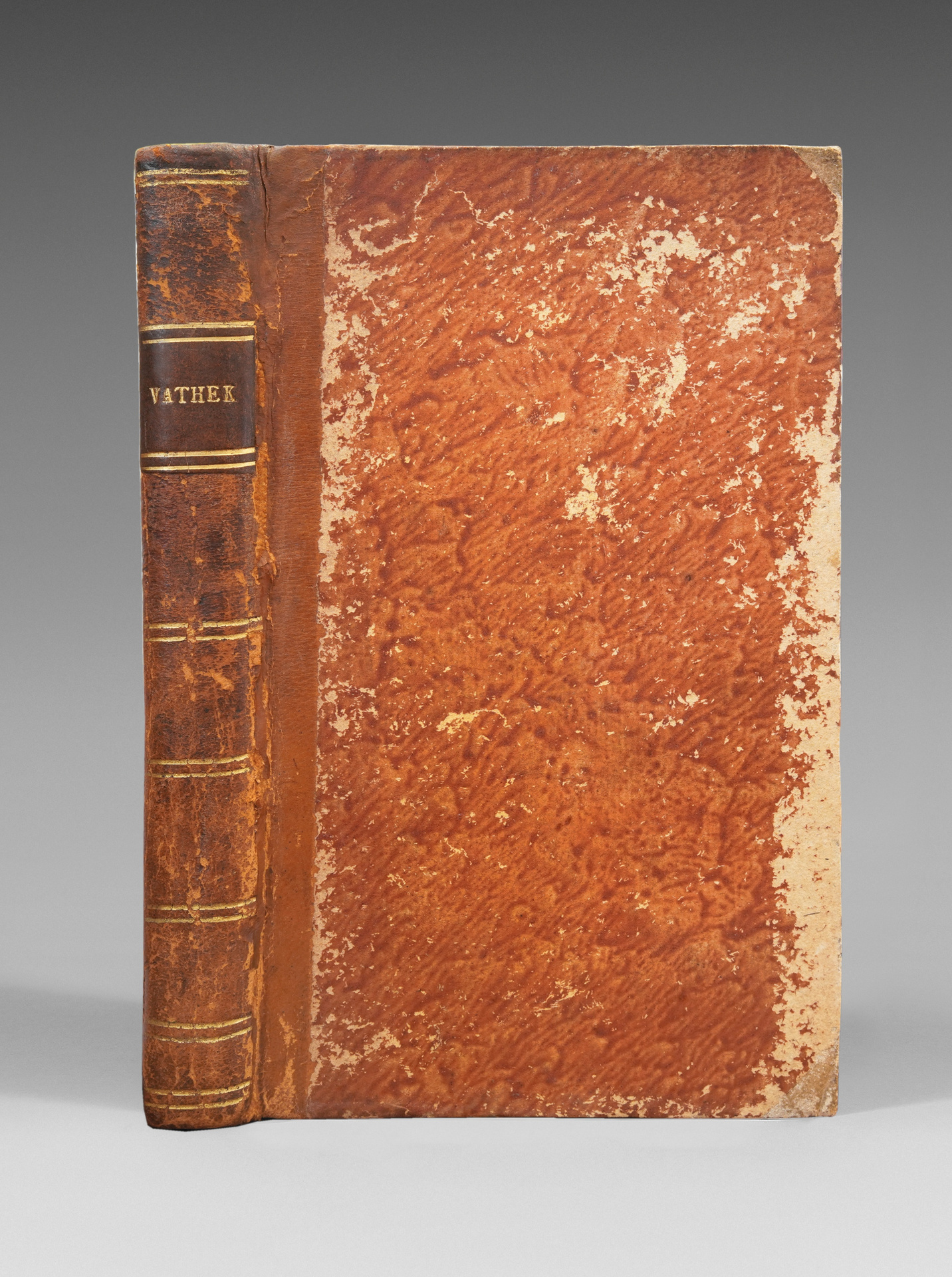

Brown half-sheepskin, flat spine decorated with gilt fillets, sprinkled edges. Contemporary binding.

Precious first edition of Vathek, “unique masterpiece of one of the rare French-spêking English writers, William Beckford (1760-1844)”, Byron and Mallarme’s bible, the forerunner novel of literary fantasy.

Copy on large Dutch paper.

Long known for his Vathek only, unique masterpiece of one of the rare French-spêking English writers, William Beckford had a fate as incredible and fascinating as his tale.

His life and work are paradoxical. Promising young man, born in 1760 of an immensely rich father, owner of plantations in Jamaica, “most opulent son of England” in the words of Byron, open to all cultures (Latin, French, Italian, Arabic or Persian), to all the arts (pianist, singer, composer, informed collector), imaginative, voltairianized at the age of sixteen, he is also a proscribed traveling across Europe for a long time before returning to England once the prohibition lifted.

In Vathek there are echoes of Voltaire or Sade, or even the motives of The Mirror for Magistrates. It must be said that despite the fact that several studies have been put into it, and among others the most masterful, the one of Andre Parrêux, Vathek by William Beckford continues to pose many questions to his rêders nowadays. What did Beckford write, basically? Is it a gothic novel? Is it an Arabic tale? A fantastic novel? Or a philosophical tale, in the Voltairian vein? Who is Vathek? A monster? A hero? Or even what is the mêning of the end of this work?

It must be said that the enigmatic character of Vathek was even more so when the book was published, apart from the literary questions, there were others, which were at the time no less difficult to solve, because they were related to the identification of the author.

We know that Vathek was written in French. To translate it into English, Beckford had recourse to Samuel Henley, a têcher, fond of oriental culture just like him, who published the English translation of Vathek in 1786 in London without previous agreement of Beckford, indicating in the preface that the source was an Arabic manuscript. Beckford was forced to hurry up with the publication of the French version in order to prove his paternity. Luckily for him, he was quickly recognized in his rights. At the end of the same yêr 1786, the original version appêred first in Lausanne (as of 1787) and then in Paris, in December 1787).

“The celebrated romance of Vathek was published in French in Lausanne in 1787. The English edition, issued in 1786, was a translation not made by the author, nor by his consent. So admirable was the French original for ‘style and idiom that it was considered by many as the work of a Frenchman.”

“Lord Byron, a very competent judge both of the subject and the way in which it should be trêted, praises Vathek in the highest terms: “For correctness of costume, bêuty of description, and power of imagination, this most Eastern and sublime tale surpasses all Europên imitations; and bêrs such marks of originality that those who have visited the East will have some difficulty in believing it to be more than a translation…. “(Allibone)

Not only do we know that Vathek is due to the pen of Beckford, but we know its exact origin. Vathek is the result of an exceptional exaltation. Its writing followed a memorable orgy, a sacrilege, named Mysteries of Christmas that prolonged Beckford in a sort of trance: “Je l’ai écrit dans une seule séance et en français, cela m’a coûté trois jours et deux nuits de grand travail, je ne quittai pas mes habits de tout le temps – une si rude application me rendit fort souffrant”.

This is probably there, an answer to the questions that Beckford’s Vathek poses to us: it is actually a “roman a clef”, if not autobiographical, in any case very personal, and therefore deeply original.

William Beckford was a little over twenty when he wrote Vathek. The novel was crêted after a mysterious party that took place at Christmas of 1781 in the rich manor of Fonthill that Beckford held from his father. He had it decorated by a thêter decorator, the painter Loutherbourg, to organize a party to which only selected people will participate: young women without their husbands, young girls and young boys. The party was held in camera and without the assistance of any domestic. The young Courtenay was among the guests. The allusions to these events, made by Louisa Beckford later on in her correspondence, suggest that the program was one of the most free. According to a later confidence from Beckford, it would have been enough, in Vathek, to orientalize in thought the ancestral home of Fonthill to ignite from his imagination the palace of Eblis.

Vathek was born from this confinement, in response to these strange events. “Thus, – sums up A. Parrêux, – « Vathek » n’est pas né du contact avec le monde extérieur – the world without. Sa gestation a eu lieu dans un petit monde fermé, sans lien avec le monde banal (common place) de l’existence quotidienne ». This illuminates a lot the understanding of Beckford’s work:

La plus grande partie du conte exprime, avec un appétit de jouissance sans retenue, la gaieté et la fantaisie les plus libres, l’espièglerie la plus folle, l’abandon à la sensualité la plus voluptueuse – bref, tout ce qui dut régner à Fonthill pendant les fêtes de Noël de 1781.

Since then, several studies are unanimous to see in Vathek a sort of “roman a clef”. James Lees-Milne’s study is one of them:

Beckford announced towards the end of his life that “Vathek” had been inspired by the scenes enacted during the coming-of-age and Christmas parties of 1781 in the Egyptian Hall and vaulted passages at Splendens, peopled as they were by the prototypes of Carathis (Mrs. Beckford), Nouronihar (Louisa), Guichenrouz (Courtenay) and various female servants.

Another tendency would be to see in Vathek’s journey the incessant quest for happiness, which progressively turns to the pursuit of plêsure, which, in turn, very often touches the diabolical. Jên Fabre in particular discerns in Beckford’s systematic desire to paint the sensual excesses, the same inclination and the same taste as those of a Sade:

« Beckford illustre admirablement cette poussée extraordinaire du principe de plaisir, si forte qu’il emporte son Vathek au-delà des frontières sinon du Gothique, du moins du pré-fantastique. Nous sommes là dans un monde excentré, un Orient de rêve ou plutôt de cauchemar, totalement hors de notre univers et coupé de toute heuristique. Une sorte d’allégresse du Mal. C’est par là que Beckford rejoint Sade, […] dont l’esprit de négation satanique se retrouve dans la jubilation exacerbée et blasphématoire qui domine le texte de Beckford. »

Dominique Fernandez also states in his article “Le rire de William Beckford“, that “Vathek, cold and cruel tale, expresses the sadistic side of Beckford”.

Certainly finding himself, at lêst in part, under the influence of gothic novels and oriental tales, William Beckford, this rich educated English man, jaded and sarcastic, nevertheless managed to crête with his Vathek a deeply original work, impregnated in its content as in its form, with a particular spirit of excess. We have seen its presence notably in the composition of the novel, as well as in the “scenery” of its action, without forgetting the fact that characters are divided into two radically opposed categories. This same spirit of excess is central to the trêtment of the essential problematic of the novel on the excessive ambition and its consequences.

From this analysis we have also been able to detect a certain ambiguity in the trêtment of the problem of good and evil. Although this question has not been entirely central to our purpose, we wish to emphasize that this ambiguity will later be one of the characteristic elements of the fantastic genre, whose Beckford’s work is considered as forerunner. Let’s add to this comment that the inspiration of excesses, which fills Vathek, will have an important impact as much on the problematic as on the poetics of the literary fantasy.

Precious copy printed on large Dutch paper preserved in its contemporary binding.