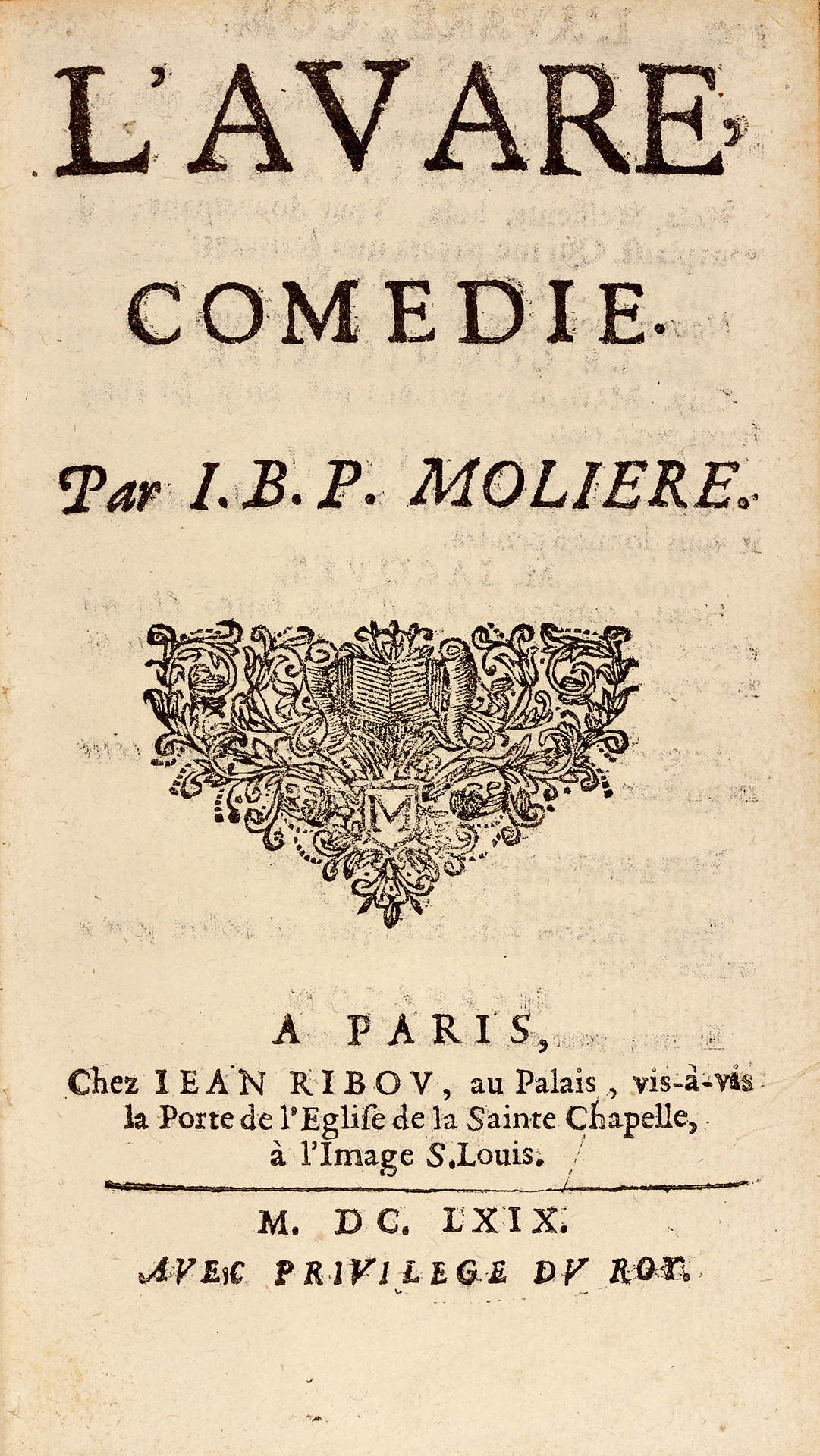

Paris, Jean Ribou, 1669.

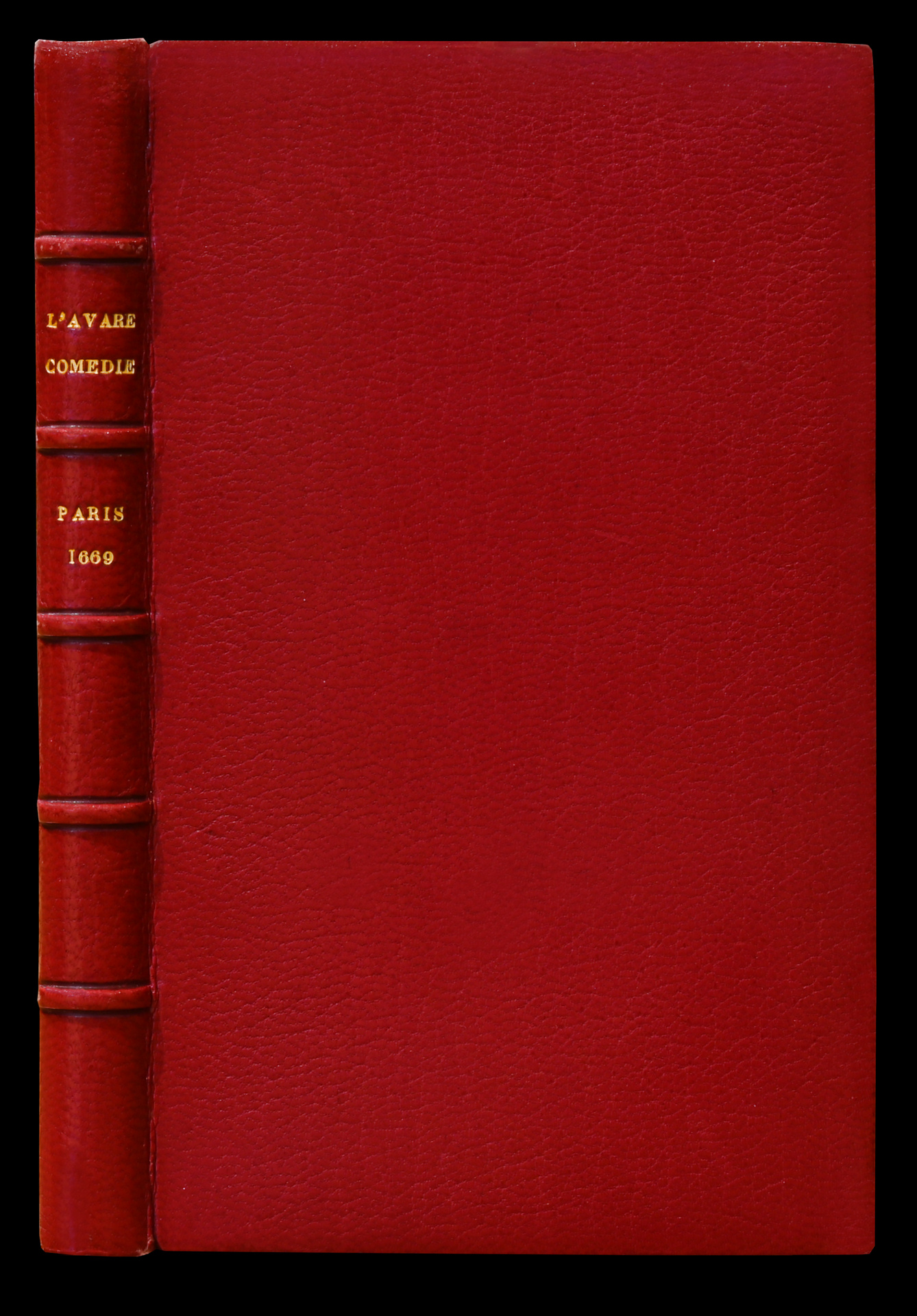

12mo of (2) ll. and 150 pp. Full jansenist red morocco, ribbed spine, inner gilt border, gilt edges. Binding signed Thibaron-Joly.

138 x 80 mm.

First edition of one of the rarest and most famous comedies of Molière.

“This comedy, rare in its first edition, has been printed with care.” (Guibert, Molière, bibliographie des œuvres, I, p. 243).

“L’Avare, one of Molière’s most famous comedies”. (G.F.)

“L’Avare of Molière, if he owes a lot to the ‘Euclion’ of Plautus (the sickly aspect of his avarice, suspicious, worried, his obsession for his cassette full of gold), is at the same time humanized (he is in love, which leads him to oppose his avarice), rooted in a society (he is also a usurer) and made more comical than his model by numerous buffoonish scenes in which he is the center. At the same time, Euclion, now Harpagon, appears as a perfect Molière character, whose behavior determines the action: he wants to marry his daughter to a man who satisfies his madness, in this case to the old Anselme who has agreed to take Elise “without a dowry. But these two aspects, Molière has set them in a framework of Italian comedy of intrigue: Valère, Élise’s lover, has broken into Harpagon’s home as house steward (but his efforts to prevent the marriage are both futile and comical); Cléante, victim of his father Harpagon’s avarice, is in love with the young and poor Mariane and finds himself his father’s rival in love. Cléante thus reproduces the type of the baron in love of the Italian comedy by wishing to marry this same Mariane who is brought to him by a matchmaker; as a result, the young man, like all young lovers of comedy, must rely on his valet La Flèche to satisfy his wishes, and if the latter’s industry ensures part of the denouement, since by stealing Harpagon’s cassette he forces the latter to consent to the marriage of his son with Mariane, the other part of this denouement, the most developed, is based on a double recognition: Valère and Mariane are recognized as the son and daughter of Anselme. Anselme can thus step aside in favor of his son, who will marry Élise, and confirm the union of Mariane and Cléante – taking on all the expenses of the double marriage, including the costume of Harpagon, whose failures have not cured him of his avaricious madness. Since the XVIIth century, this denouement has often been criticized in the name of verisimilitude, just as those of “L’École des femmes” and “Les Fourberies de Scapin” are criticized. This has given rise to the idea that Molière botched his endings. This is to forget that, by resorting to this type of ending, Molière explicitly attached himself to a tradition, since recognition is systematic in the comedy of intrigue. It is thus understandable that a playwright could be attached to “naturalness”, and therefore to verisimilitude, in the words and actions of his characters, but neglect verisimilitude in everything that touches on the comic tradition. For Molière, the denouement is precisely the part of the work that can dispense with any reference to naturalness; provided that it is in keeping with the type of play he is completing. ‘L’Avare’ is the most striking demonstration of this.” G. F.

“L’Avare is one of Molière’s most remarkable plays, performed in 1668 […] this Molière’s play is a masterpiece: the character of the miser, which reminds us of Plautus’ ‘The Marmite’, surpasses it by its depth. The bitterness that Molière brings to the analysis of this devastating passion explains the little success that the play had at its beginning. Harpagon’s character is not modified in any way by his feelings of love: even on this point his avarice does not slacken. The rivalry which opposes him to his son hurts him like an insult to his rights of father and master. But in reality his vice has the most deplorable repercussions on the life of his children. And this is what gives the play its dark color, which makes it seem like a drama.

On the theme of “The Miser” were composed melodramas among which we must mention: The Miser by Giuseppe Sarti (1729-1802), Venice, 1777; those of Giovanni Simone Mayr (1763-1845), Venice, 1799; by Fernand Orlandi (1777-1848), Bologna, 1801. With the same title, Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) and Francesco Bianchi (1752-1810) composed two interludes which were performed in Paris, respectively in 1802 and 1804.” (Dictionary of Works, I, 334).

One of the great texts of French literature, strongly “rare in its original edition”. (Guibert).