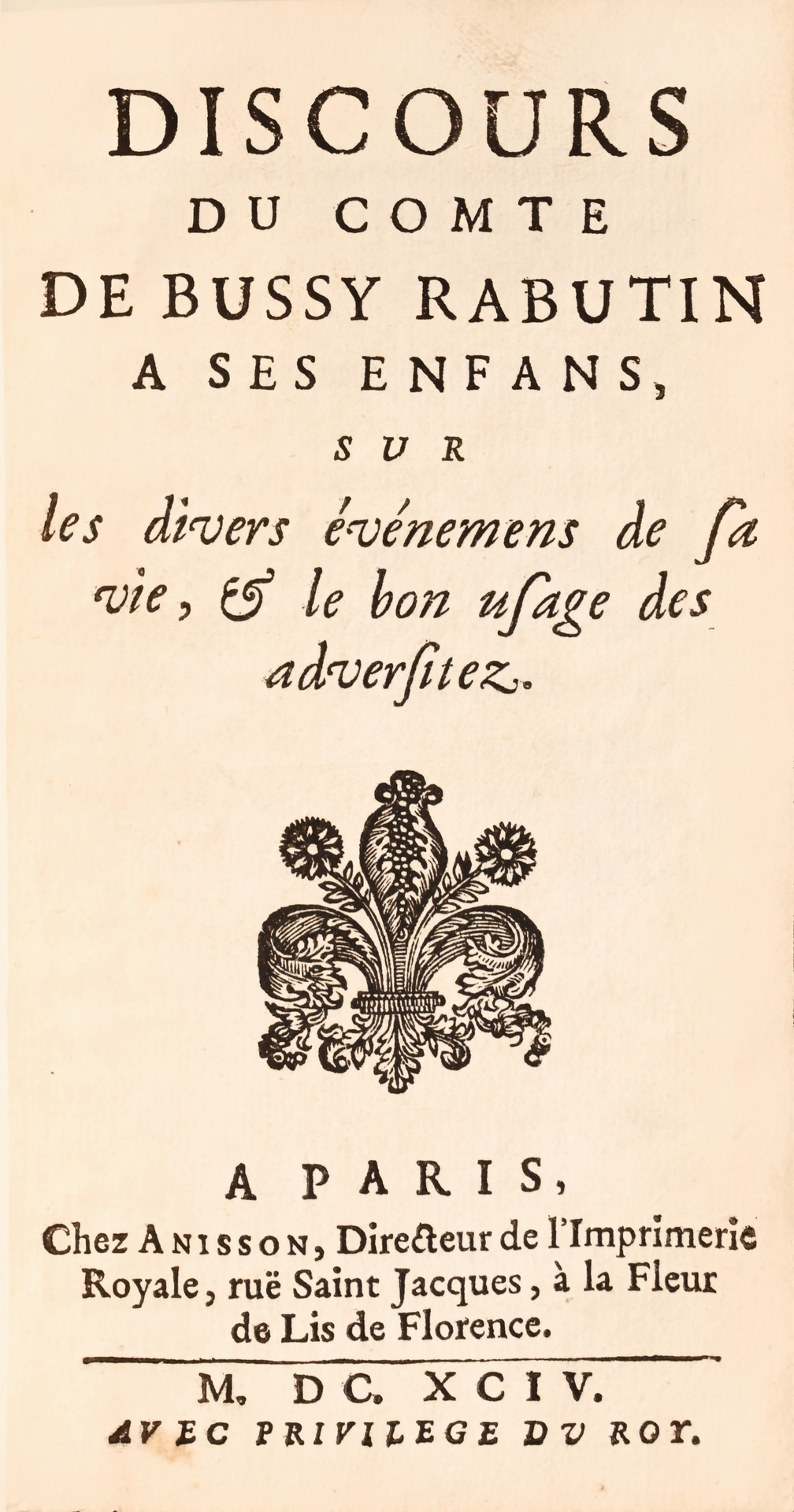

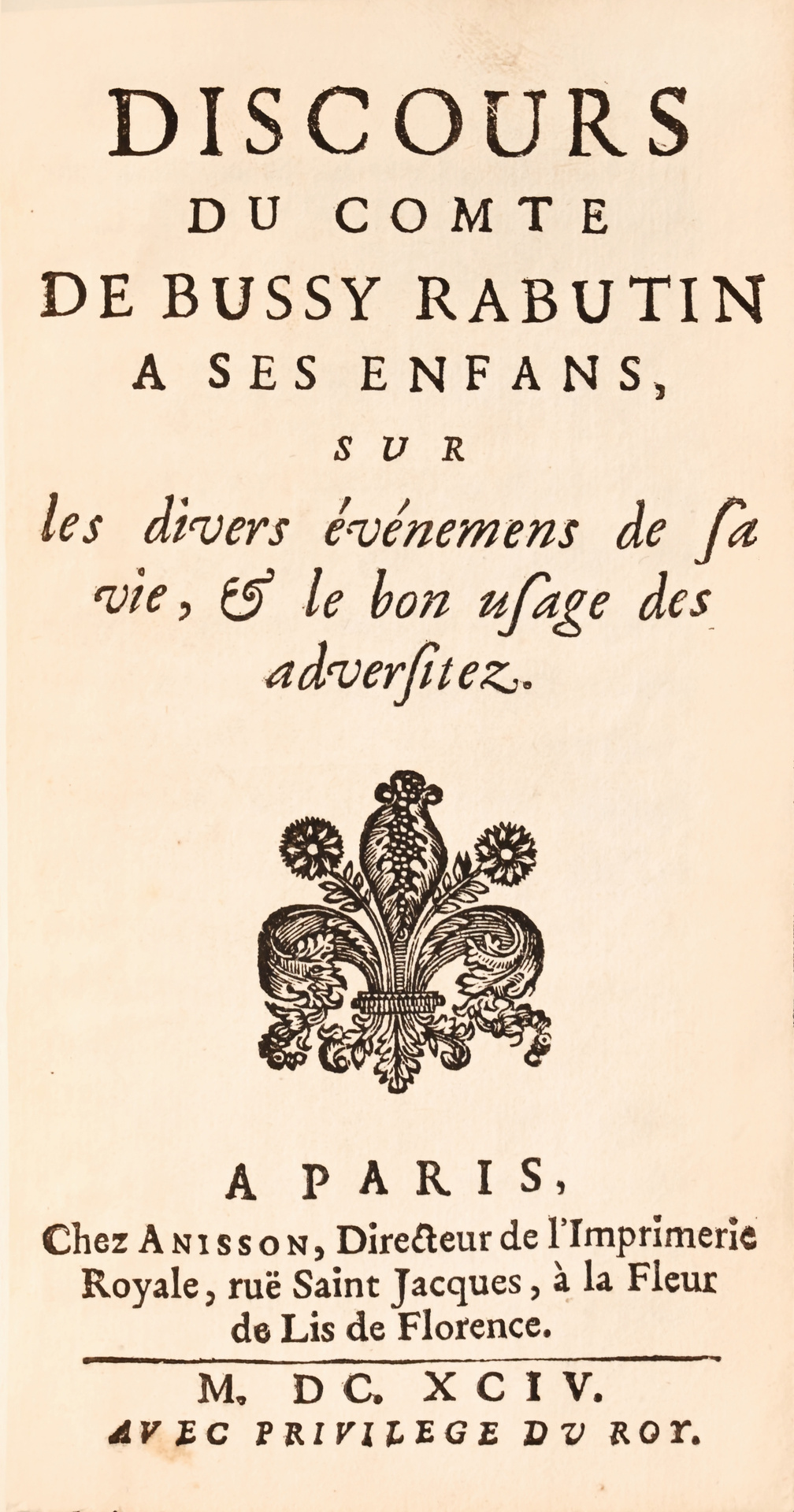

Paris, Anisson, 1694.

12mo of (4) ll., 350 pp., (7) ll. Brown calf, spine ribbed and decorated, red mottled edges. Contemporary binding

145 x 80 mm.

First edition of this famous text recorded by this very rare copy unknown to Tchemerzine.

This text, one of Bussy’s most intimate, was published the year after his death, in 1694, by Jean Anisson, under the title: “Discours du Comte de Bussy-Rabutin à ses enfants”.

The “Discourse” will then be inserted in the “Memoirs” of the Count of Bussy Rabutin and many times reprinted from 1696.

“It is necessary to write like Bussy“, advised La Bruyère.

“A pro domo plea, a moral testament, a page of history, this original edition is a literary work in its own right where Bussy’s art of writing is revealed…” (Daniel-Henri Vincent).

The Count of Bussy-Rabutin, Great of the Kingdom of France born in 1618, cousin of Mrs de Sevigne, with whom he shared a passion and talent for epistolary writing and memoirs, fought throughout Europe at the head of his regiment, survived the Fronde and the most diverse conspiracies, and then lived the life of a courtier with the aging Louis XIII and the young Louis XIV. However, he spent his last thirty years in Burgundy, exiled to his castle by the king after being imprisoned for a few months, the monarch having put up with neither his friendship with Fouquet nor the libertine mockery of the “Histoire amoureuse des Gaules“, which portrayed him as a seductive Jupiter. It is there, in his “small Burgundian Versailles”, that Bussy-Rabutin wrote his “Memoirs” and his “Discourses” to his children.

His style is elegant, precise and lively. This tone and inspiration lead him to describe in a personal way his adventures, from his native Burgundy to the Court, but also far away, in France or in Europe, or in the living room, the boudoir, or even the bed, of his numerous conquests. He kept an extremely caustic pen to ironize the powerful of Versailles. This memoirist’s work has long been considered as first-rate, reedited from the seventeenth to our days.

Already in the eighteenth century, the Marquise du Deffand admired the style of Bussy.

“Who was Roger de Bussy-Rabutin? The name is not unknown to any educated French, but, if we place him in the heart of the seventeenth century (1618-1693), we can hardly see in him a cousin and correspondent of the most famous Marquise de Sevigne. “One must write like Bussy”, advises La Bruyère. Daniel des Brosses reveals to us a completely different Bussy, a man of the sword, Mestre de Camp General of the light cavalry of France, vainly seeking the baton of Marshal, appreciated by Condé before being his adversary, praised by Conti, recognized by Turenne, but dismissed from office by Mazarin’s distrust, the cabals of the Court, Condé’s final hatred, the slanders believed by the king who exiled him (atrocious punishment which consisted in staying at home) for many years, while he begged to serve. When he returned in grace, he was struck by the conclusion of a sordid trial and retired, this time voluntarily… “

Yves-Henri Allard – November 2011.

The text of this original known by this extremely rare copy begins as follows:

« Quand je fais réflexion mes enfants aux traverses de ma vie, que je considère les marques d’Honneur, les grands titres et les grands établissements refusés à ma naissance, à mes longs services et à mes grands emplois. Je rends grace à Dieu d’avoir emploié la mauvaise fortune pour m’attirer à luy, prévoyant que je me serais perdu dans la bonne.

Je ne veux pas dire par la que tous les gens heureux soient reprouvés. Il n’y a jamais eu une fortune si longue, ny si brillante que celle du Roy. Cependant il n’y a jamais eu une plus solide vertu que la sienne. Je connais encore des gens à la cour qui vivent dans les prospérités comme des anges, mais j’en connais fort peu et ma fragilité me fait croire que je n’aurais pas été du petit nombre.

Outre le profit que je prétends tirer de mes disgraces mes enfants, je veux aussy vous en faire

profiter en vous faisant comprendre le peu d’état que l’on doit faire des belles apparences de la fortune et de la fortune même, non seulement par ma propre expérience, mais encore celle d’une partie des gens de qualité malheureux des siècles passés… ».

In 2000, Éditions de l’Armançon published the Discours du Comte de Bussy-Rabutin à ses enfants, according to the autograph manuscript of the Mazarine library, with this complete analysis:

« L’affaire est évidemment d’importance pour la connaissance de l’œuvre du gentilhomme bourguignon car, après sa mort, les éditeurs ont apporté de nombreuses et importantes modifications à ses écrits en vue de leur publication ».

The Discours à ses enfants consists of a short introduction and two distinct parts, of unequal importance. The latter, which Bussy explicitly addresses to his children, is a reflection on his disgrace which kept him in exile for seventeen years by order of Louis XIV and away from the Court for even longer. Although he considers his misfortune unjust, far from complaining about it, he claims to be happy about it since it allowed him to make his salvation whereas a happy and worldly existence would certainly have kept him away from God. Beyond his personal case, Bussy claims to draw a moral lesson from the life of other unfortunate people, whom he names unfortunates, on the appearances of fortune and social success opposed to the true wealth, which is in God. Naturally these unfortunates, all good people, are generally innocent, victims of their enemies and, perhaps, chosen by God.

Bussy first recounts the Lives of seventeen illustrious unfortunates.

The second part, which covers half of the work, is indeed entirely devoted to Roger de Rabutin Bussy. The author admits naively : « je n’ay plus pour finir ce discours qu’a vous parler de moy pour qui je vous ay parlé de tous les autres ». He justifies the place that he grants to himself by the knowledge that he has of his own life: « je scay mieux ce que j’ai fait que ce qu’ont fait ceux dont je vous ay parlé ». Moreover, his children must naturally be interested in the history of their father.

It is about memoirs where the part reserved for his military campaigns, and thus to his merits, is dominant. As for other unfortunates, Bussy explains his disgrace not by his errors or his faults but by the action of his adversaries: “Peace was the height of my disgraces; because during the war my services supported me against my enemies, instead of peace putting me at their discretion”. The marshal of Turenne is in the first rank of those who harmed him.

Bussy pushes as far as possible the thesis, obviously false, of a king benevolent towards him, abused by his entourage and obliged to compromise with his powerful detractors. He reproaches Louis XIV only for his rudeness. For his exile, Bussy does not deny that the diffusion of his satirical novel, the Histoire amoureuse des Gaules, is the cause. But less because the king would have been dissatisfied than because of the scandal caused by falsifications of the original text. The objective of Bussy is clearly to present the king under the most favorable light, to avoid any subject of conflict with the sovereign, by giving him reason even in the decisions which were the most contrary to him, while remaining credible by the moderation of the praise.

The king appears even as the possible executor of the will of God with regard to Bussy: Louis, by exiling him, puts him on the way to salvation. His acts, including those which interest the private individuals, are perhaps inspired by God. A way, more skillful than it appears, to make his court.

Bussy then evokes his life of exile until 1690, some family events, his brief stays at the Court without real return in grace. He confesses his faults, proclaims his “religious fund” in two paragraphs and ends on a quatrain that an epicurean would not disavow.

It is therefore exaggerated to see only the moralizing work of a devout person, with a dogmatic tone. If the moral dimension cannot be denied, with its religious references, Bussy shows himself above all as a memorialist, with an ambition of historian. The very nature of the Discourse seems more complex than it may appear at first sight.

An instruction to his children?

The “Discours à ses enfants” can indeed be likened to a teaching that a father legitimately gives to his children, following the example of the king who wrote Instructions to the Dauphin and Memoirs. However, at the date of the writing of the text, the Rabutin children are adults, and the lesson seems very late. And as Bussy was well into his seventies, it would probably be more accurate to call the Discourse a moral testament.

The strictly private character of the Discourse seems more apparent than real. Bussy does not intend to diffuse this text, at least at the beginning: “Do not show the work to anybody” recommends Bussy to his friend Father Bouhours. Finally he announces to Bouhours that he intends it for the king. Bussy thus has other readers in sight than his children, but selected readers, and a requirement of writing above the standard of a family text. For that, Bussy brings to him all the necessary care as his correspondence with Father Bouhours shows it well.

He consults him on everything, the subject, the composition, the turns etc. This submission to the remonstrances of the Jesuit reverend can astonish. It is that Bouhours is an important pawn in the strategy of Bussy. It is indeed by him that his writings reach now by his confessor the king himself, since the death of his friend the duke of Saint-Aignan in 1687. This close friend of the king rendered this service faithfully to the exiled.

Bussy and the king

The real addressee of the Discours à ses enfants is Louis XIV, as Bussy tells Father Bouhours. The step of Bussy is not new. It was he who expressed the intention to have his works read to the sovereign, beginning with his Memoirs in 1670.

It seems quite probable that the communication to the king of the life of the Illustres malheureux has as a goal to return in grace and to obtain a material help which would allow him to leave a particularly difficult state of fortune. Bouhours serves as an intermediary. And whereas all his previous attempts were in vain, this time he obtains a pension of four thousand livres. The letters of Bussy are sufficiently explicit so that one can attribute this mark of return in grace to the effect produced by the Discourse to his family which convinced the king (or Mrs de Maintenon) of the deep moral change of Bussy or that it was time to put an end to his misfortune.

A distorted work

One year after his death, the Discourse of Bussy-Rabutin is published. His children have no part in it. The warning of the Discourse published in 1694 shows well the objective of its editors, among whom Father Bouhours, without any doubt. It is less the work of Bussy-Rabutin that interests them than the testimony of his penitence, of his return to God. Thus one can show the force of religion, the superiority of Christianity which ends up triumphing over the strong spirits, the libertines such as Bussy admits himself to have been.

Manuscripts recorded:

Three manuscript versions of this literary text are known today, all in the public domain. Their text and composition differ significantly.

1) Manuscript of the municipal library of Dijon, not autograph, bound in simple worn calf. This is a slightly later copy of the autograph manuscript.

“On October 16, 2010, a manuscript by the Count of Bussy-Rabutin, entitled “Discours à sa famille en mars 1691” (Speech to his family in March 1691), was acquired thanks to the mobilization of the Association des Amis de la Bibliothèque municipale (Association of Friends of the Municipal Library), the Société des Amis de Bussy-Rabutin (Society of the Friends of Bussy-Rabutin), the Académie de Dijon (Academy of Dijon), and donations from private individuals who are lovers of our heritage.

The text, carefully calligraphed, consists of two parts. In the first part, Bussy evokes several illustrious misfortunes such as Tobie, Belisarius, Saint Louis, François I, Bassompierre, etc. The second, and longer, is devoted to the last of this unfortunate but glorious lineage, the Count of Bussy-Rabutin himself. The Discourse of Bussy-Rabutin was first published in 1694, one year after the death of its author and heavily modified by the editors.

Two autographs are preserved. One, which Bussy probably offered to Louis XIV, is in the Bibliothèque Mazarine. It was published in 2000 by Éditions de l’Armançon. The other is in the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

This new manuscript of the Discourse, partly unpublished, probably inspired by Bussy-Rabutin’s daughter, Louise-Françoise de Coligny, countess of Dalet, presents substantial variants with the two autographs, which are themselves different from each other. This shows the interest it presents for the knowledge of the late work of the Burgundian gentleman and, singularly, on the conditions of his literary creation.

The Friends of the Municipal Library, the Friends of Bussy-Rabutin and the members of the Académie de Dijon have decided to deposit the manuscript of the Discourse at the Municipal Library in order to enrich the Burgundian heritage, to allow its conservation in the best possible conditions and to authorize its consultation by researchers. The document was solemnly entrusted to Mr. François Rebsamen, senator and mayor of Dijon, on October 16 during the formal session of the Academy, to be handed over to Mrs. Marie-Paule Rolin, director, and Mrs. Caroline Poulain, curator of the ancient collection.

This event was to be an opportunity to present original works dedicated to the Burgundian gentleman. Thus, an academic meeting was held on Bussy-Rabutin and his work, often gallant and libertine.

According to the Curator of Ancient Manuscripts, this manuscript, deposited in the Dijon Municipal Library, is a later, non-autograph copy of the “Discours à sa famille“.

2. Copy of the B.n.F. bound in simple roan :

Autograph manuscript with variants with the edition (Paris, Anisson, 1694) and bearing corrections by Louise-Françoise de Bussy-Rabutin, marquise de Coligny, on f. 8v, 12, 13v, passim.

Title : Count Roger de Bussy-Rabutin. Speech of the count of Bussy-Rabutin to his family on the good use of the adversities (Title different from our manuscript).

Gift of Baron Henri de Rothschild, 1933.

Support : Paper

Materiality : 140 leaves (125-126,136-140 blank.)

Dimensions : 240 x 180 mm.

Binding : Bound in brown roan with fillets. Inner dentelles.

3. Copy of the Mazarine library:

92 leaves; 230 x 172 mm; red morocco with the Condé arms.

The present copy, after a comparative study with the bibliography of Tchemerzine, is to this day an absolute rarity. A second, more extensive edition in 6 ll. and 454 pages, with a different title, was published in the same year 1694. It is the only one known of Tchemerzine, the one which he qualifies wrongly as original edition. In this second edition, better presented, the title is corrected and approaches the title of the original manuscript but the printer is the same one.