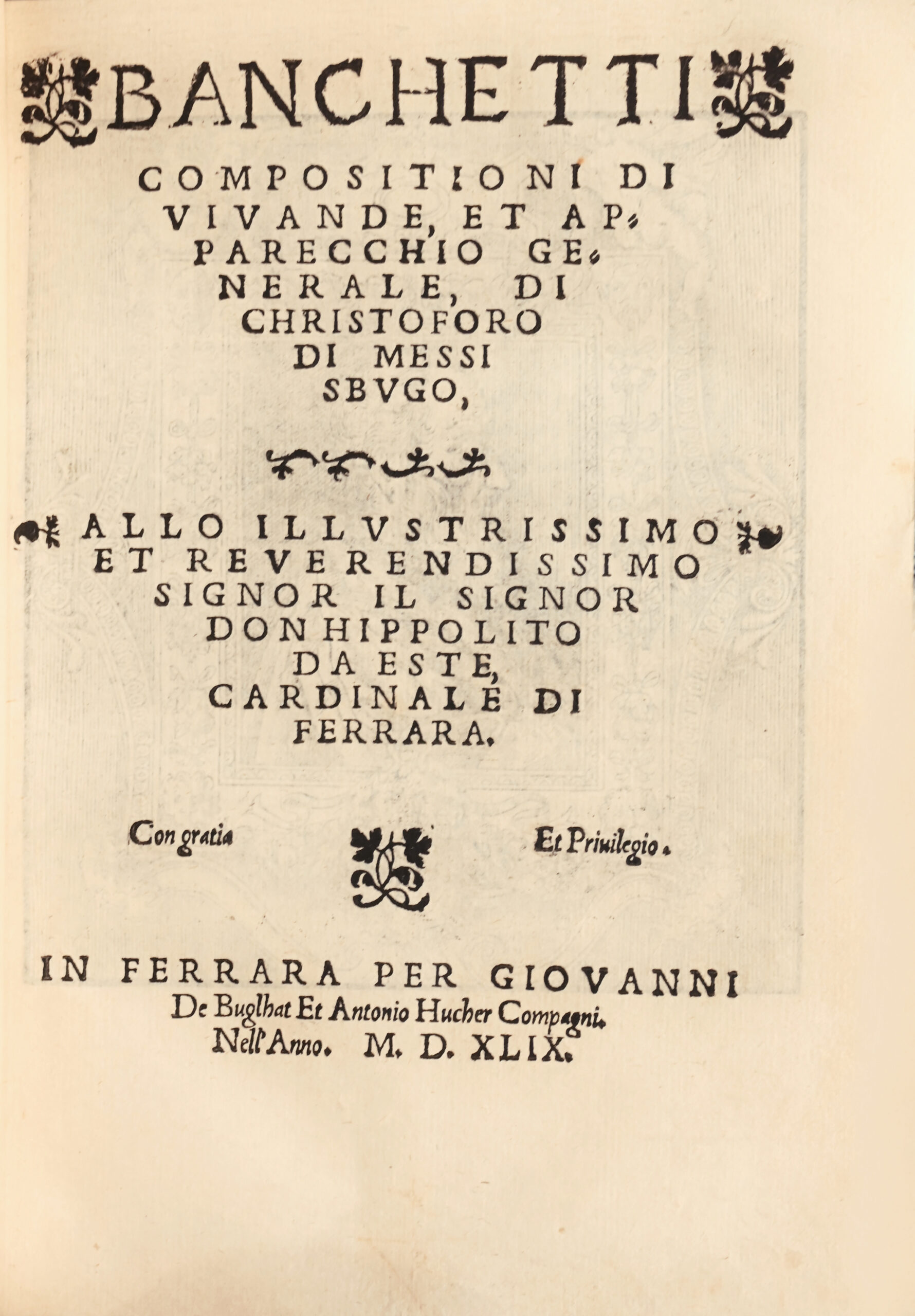

Ferrare, Giovanni de Buglhat et Antonio Hucher, 1549.

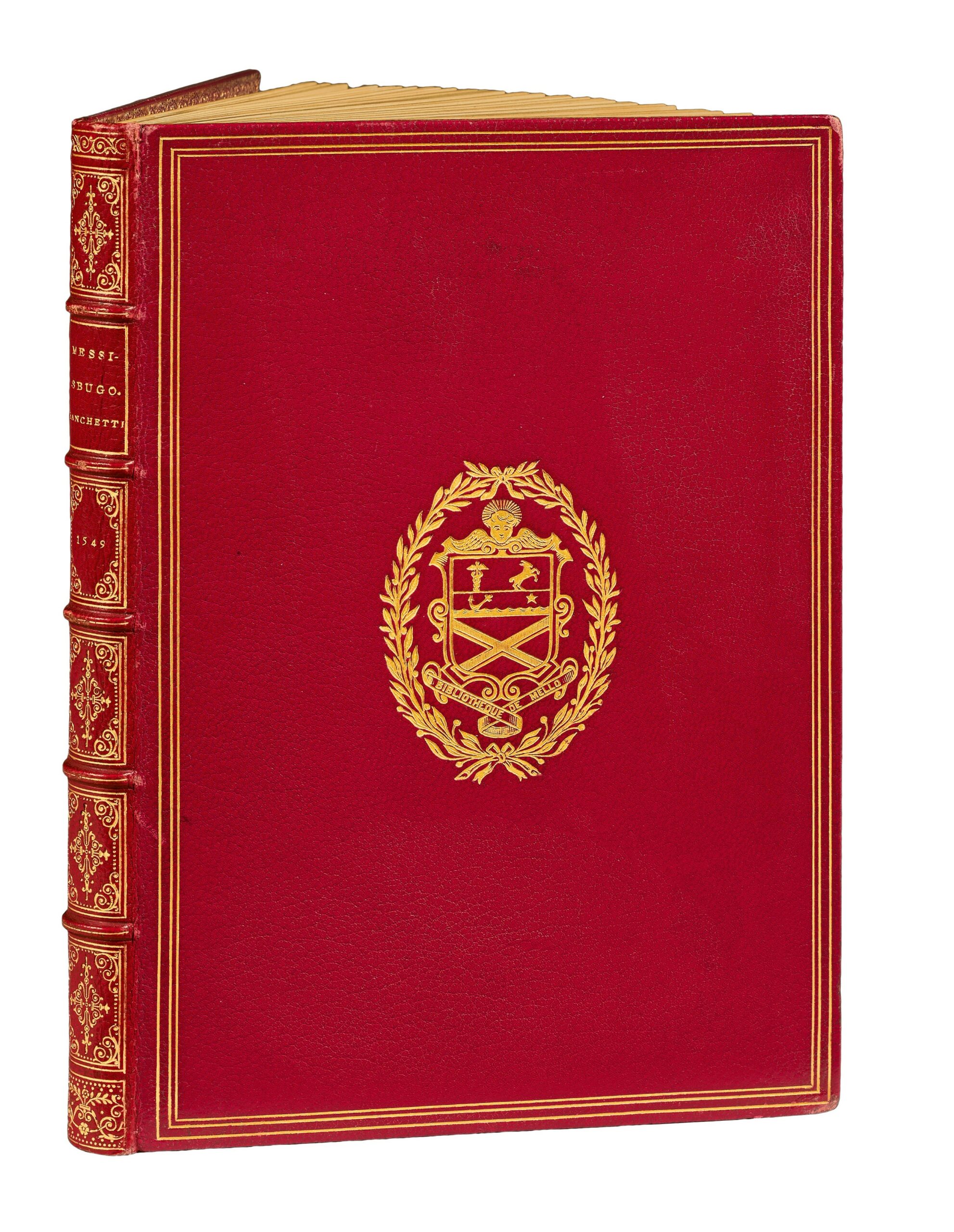

4to of (8) ll., 22 ll., (2) ll., 71 ll., (1) bl.l., (7) ll. Red morocco, three fillets around the covers, gilt coat of arms in the center, ribbed spine, panels decorated with fleurons and corner irons, friezes at the head and foot, inner border, gilt over marbled edges. Chambolle-Duru.

205 x 143 mm.

“Original edition of the greatest rarity.”

Messisbugo’s book is the most coveted jewel of all the great gastronomic libraries, and this first edition, printed in Ferrara, is missing from almost all collections. Most collectors had to be satisfied with later editions (which are also rare) given in Venice in 1552, 1556 or 1576.

The work is dedicated to the famous Hippolyte d’Esté, cardinal of Ferrara (1509-1572), son of Duke Alphonse d’Esté and the famous Lucrezia Borgia. This great patron of the arts and letters lived in his youth at the Court of Francis I. His brother, Hercules II, had married Renee of France, sister of the first wife of Francis I. In 1539, he obtained the archbishopric of Milan, then that of Lyon. In 1540, the king gave him entry into his private council. In 1546, he had the bishopric of Autun of which he resigned in 1550 for that of Narbonne. He was not less favored by Henri II.

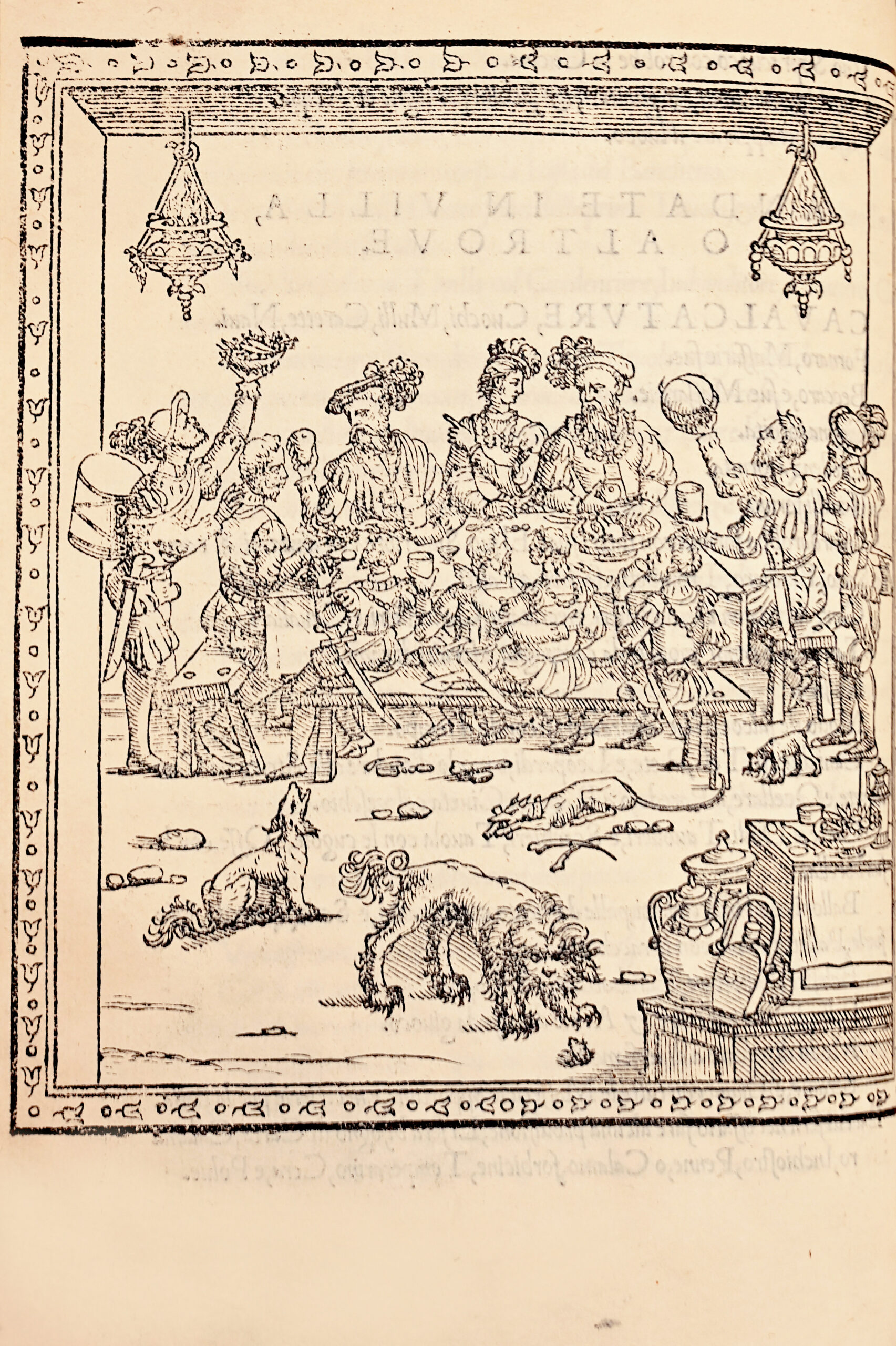

These biographical details are not irrelevant since the first part of the volume gives the description of a great number of feasts prepared by Messisbugo for this prelate and various other great characters of his family, between 1529 and 1548.

The first, on May 20, 1529, was given by Hippolyte d’Esté to his brother Hercules, then Duke of Chartres; the second was organized by Hercules d’Esté for his father and his wife Renee; another one, in 1532, was for the reception given in Mantua by Duke Alphonso d’Esté; another one, in 1543, was offered by Messisbugo in his own house to Hercules d’Esté; the last one describes a carnival feast organized by Messisbugo in his house, in February 1548, for the Duke d’Esté and some gentlemen of his friends.

It also deals with the problems of logistics, utensils, furnishings and decorations necessary for the full success of these gastronomic and political events.

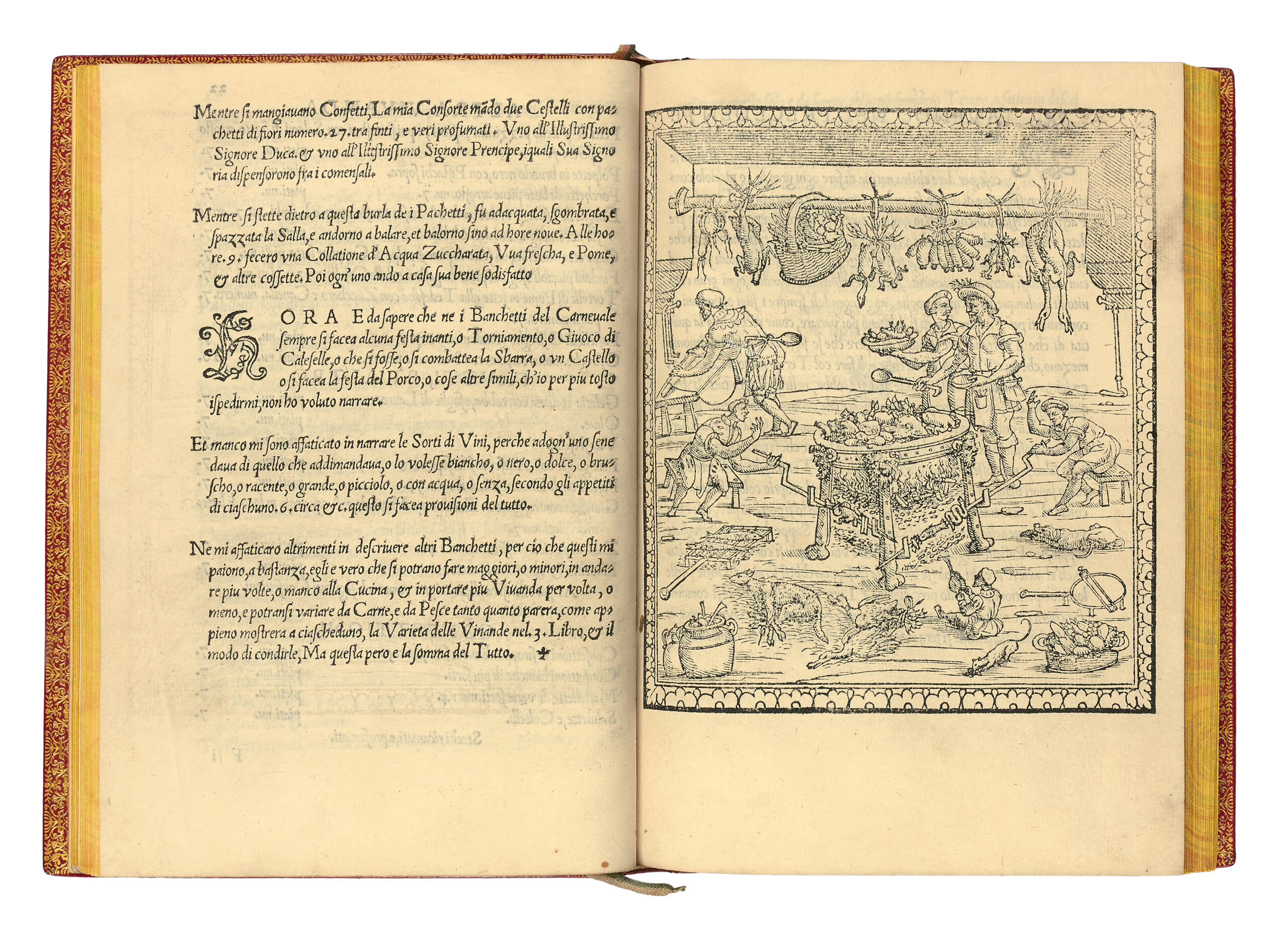

The second part, which occupies the greater part of the volume, is a true collection of recipes: “It is a first-rate document on cooking in Italy during the Renaissance: pies, pizzas, pastas, tortelletti, macaroni Neapolitan style, Roman style, lasagna, ravioli of meat, mortadella, fish, pies and pâtés, various minestres, rice dishes ; tripe of veal, lamb or kid; soups, mustard recipes, cold and hot sauces; meats, cold cuts (cervelas, mortadella, sausages); seafood; jellied dishes, etc.” (Oberlé, Fastes, 61).

The wood engraved illustration contains 3 full-page figures: a portrait of the author surrounded by a rich Renaissance frame; a plate showing a feast; another plate showing Cristoforo da Messisbugo officiating in his kitchen (these two woodcuts are attributed to one of the editors, Antonio Hucher); and the typographical mark is repeated.

An undeniable jewel of any great gastronomic library and a precious testimony to the permanence of Italian taste under the reign of François 1, this first edition is missing from almost all specialized collections, most enthusiasts having had to be satisfied with later (and rare) editions given in Venice in 1552, 1556 or 1576.

A very fine copy, with wide margins, bound by Chambolle-Duru in morocco and bearing the arms of baron Achille Seilliere.