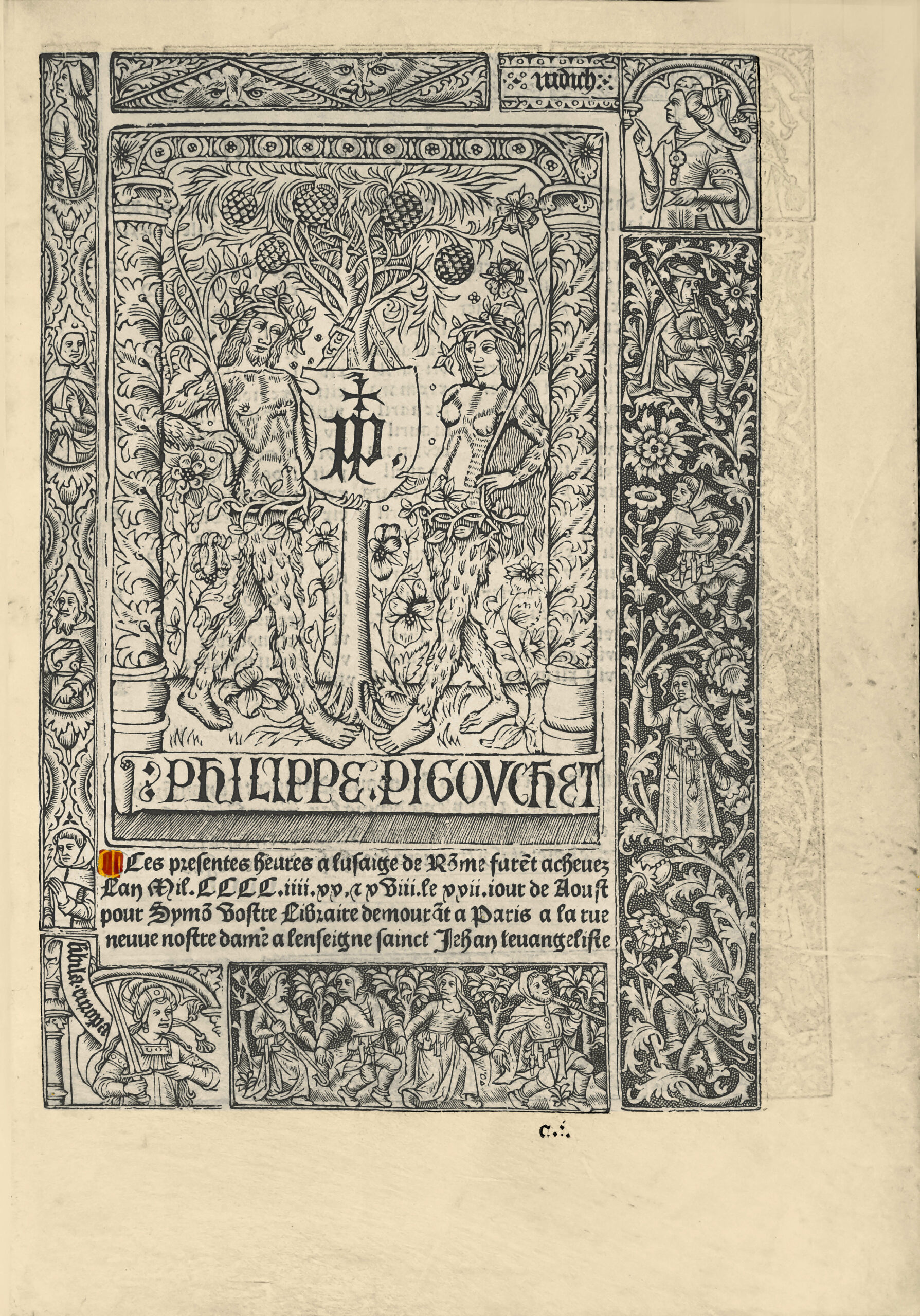

22 août 1498.

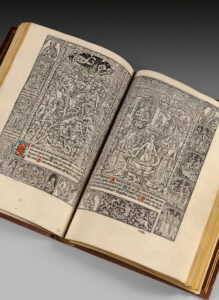

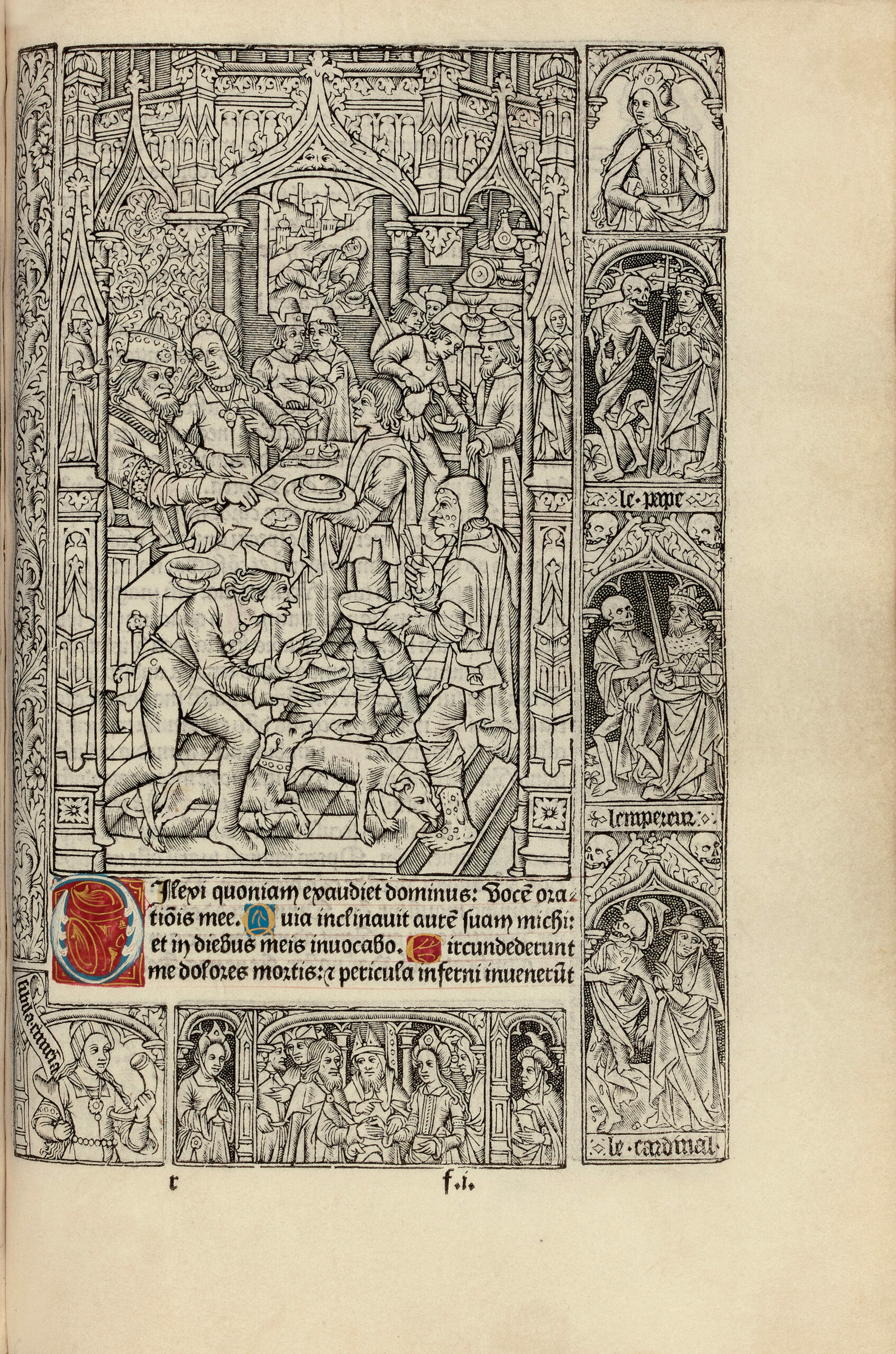

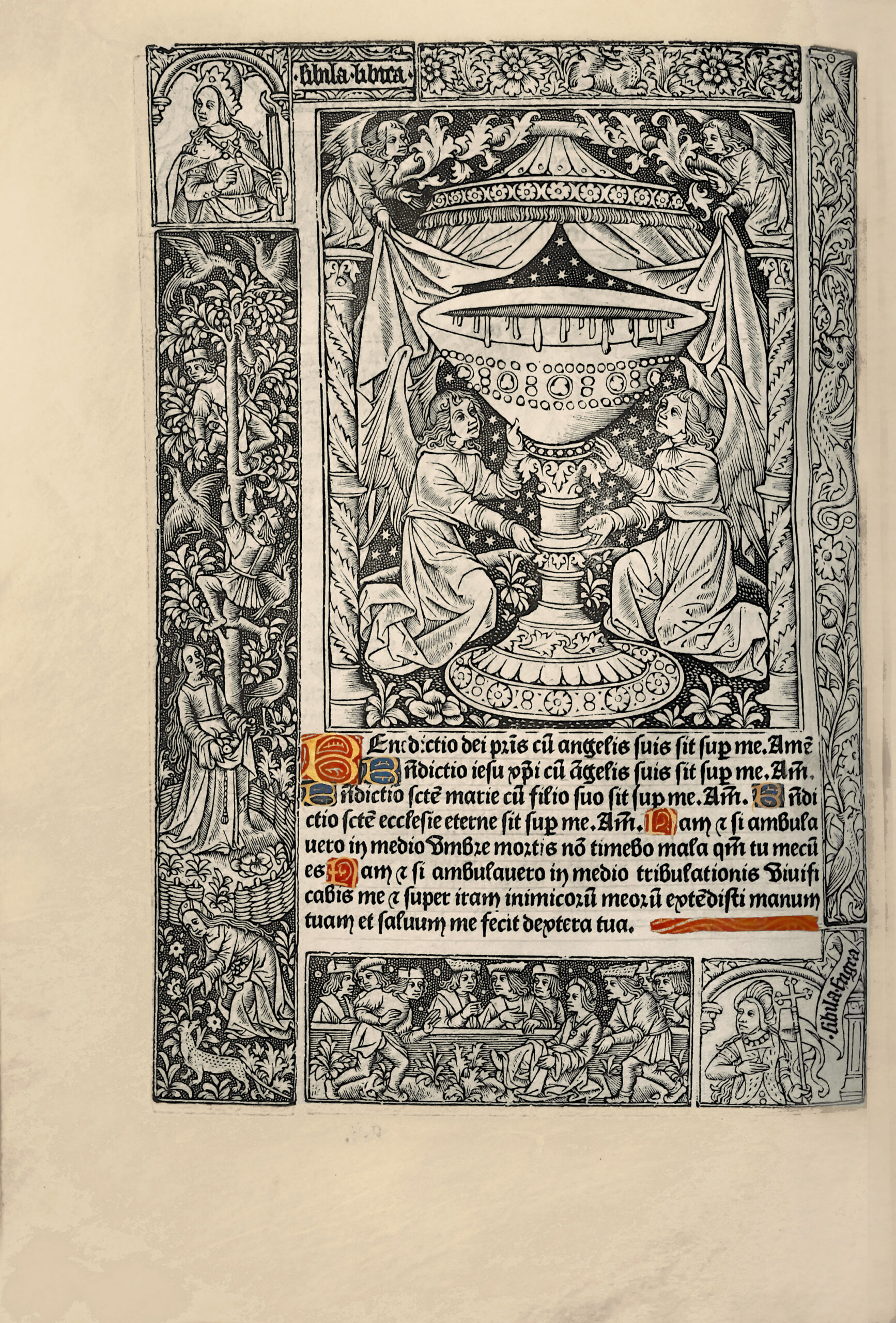

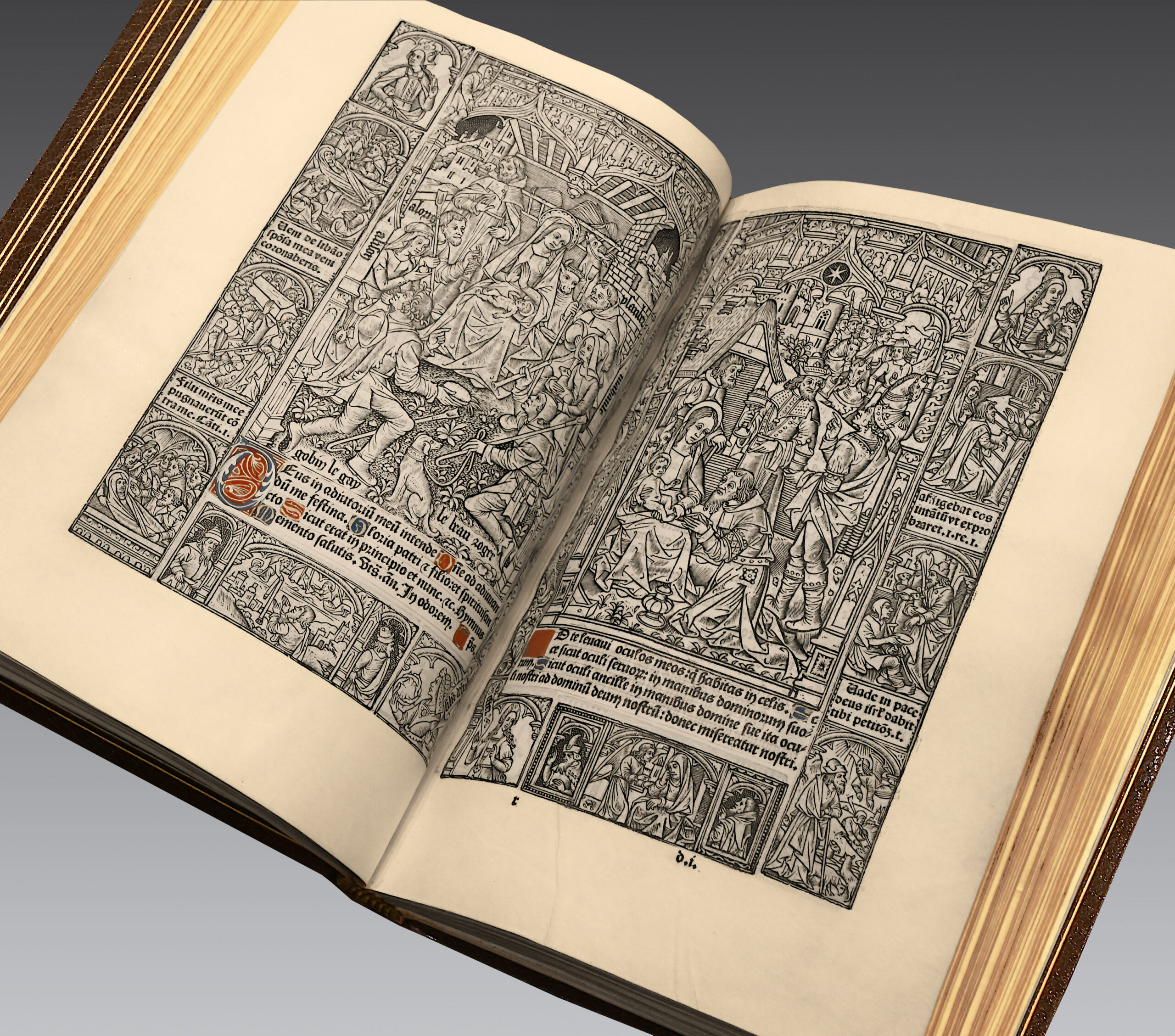

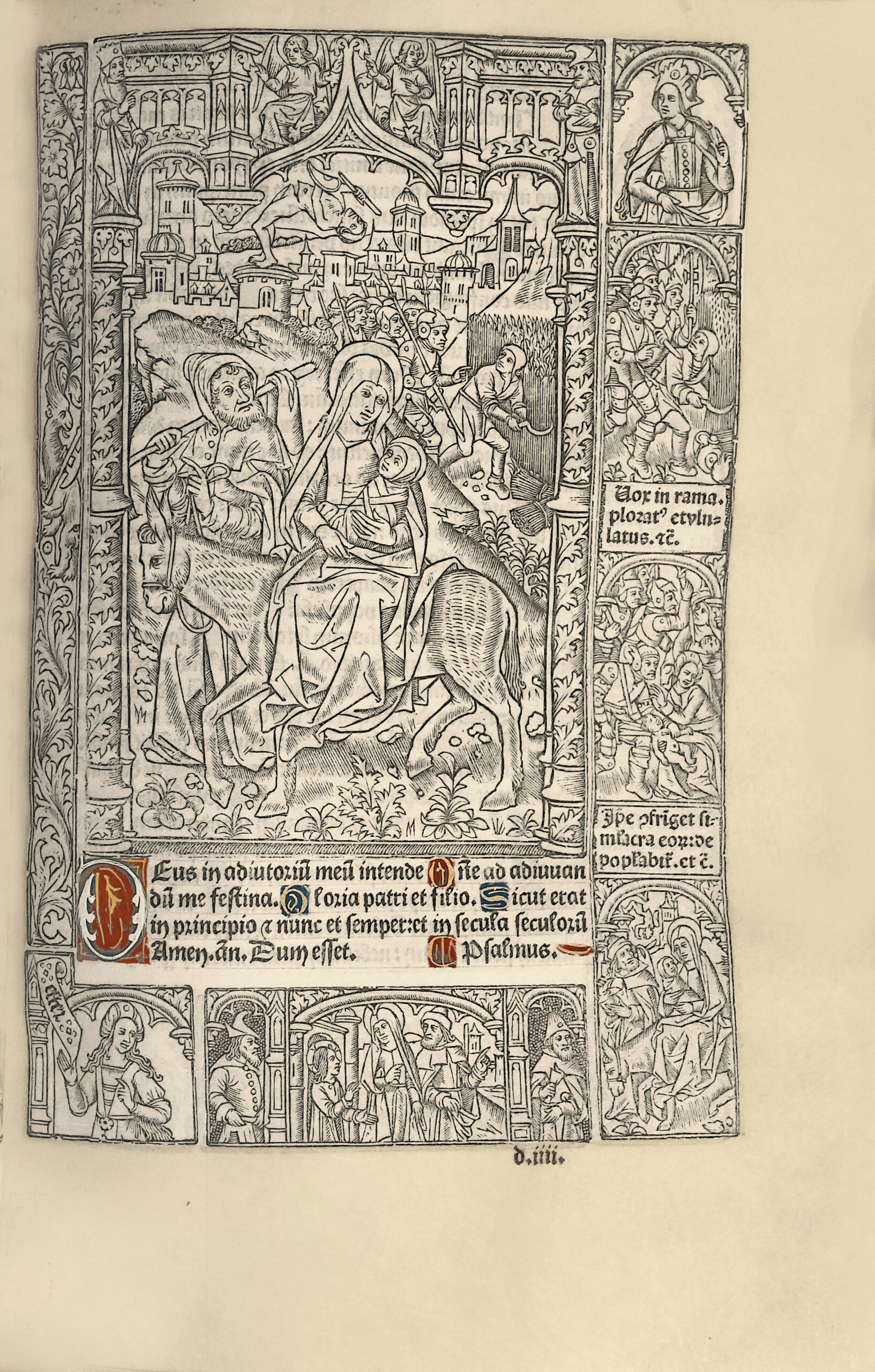

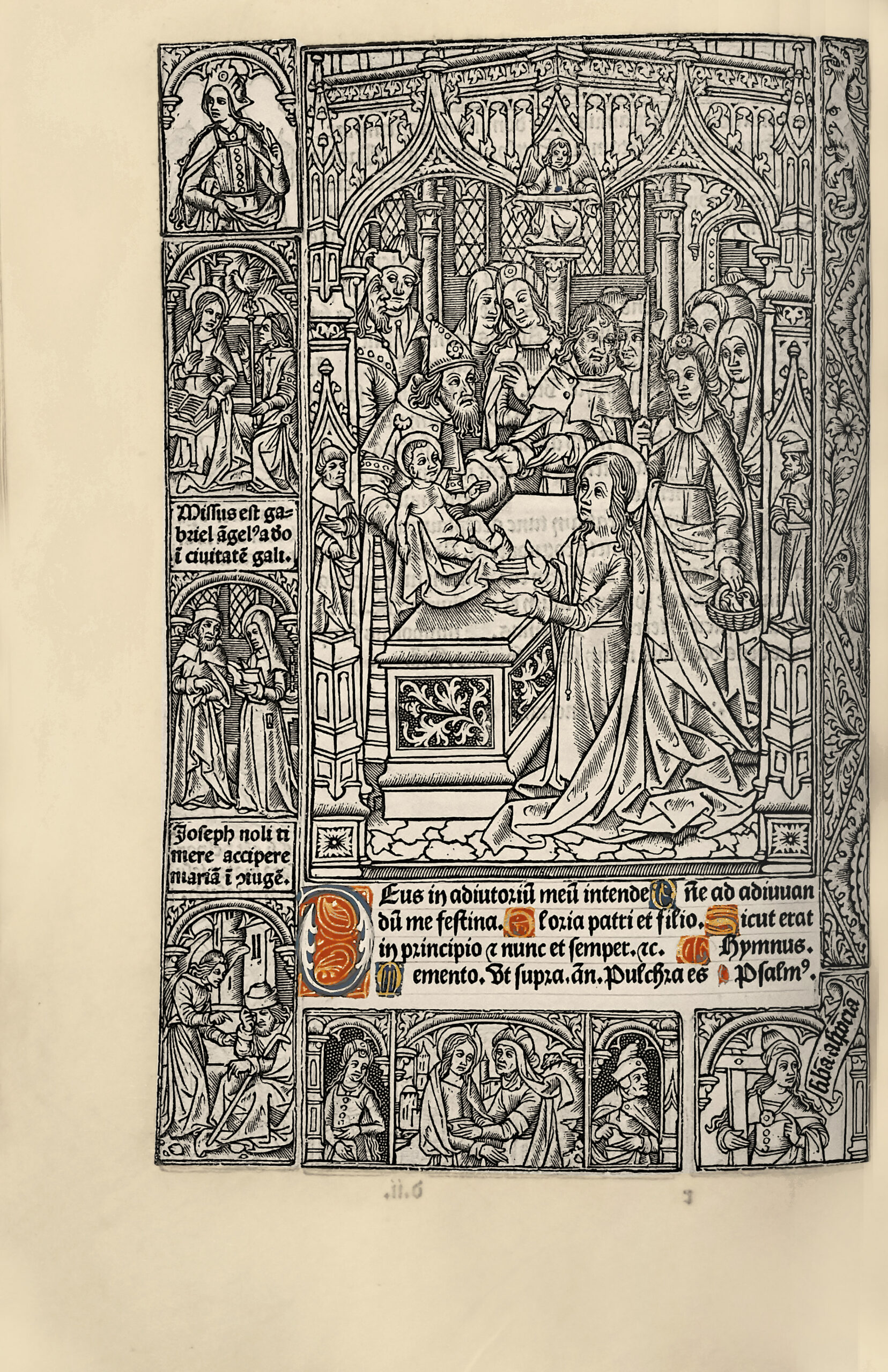

Small gothic 4to [208 x 145 mm] printed on vellum skin of (72) ll., a-i8, 33 lines per page, mark of the printer on the title, historiated borders on êch page, 21 large full-page engravings not including the anatomical man, numerous small initials illuminated with gold on red or blue background.

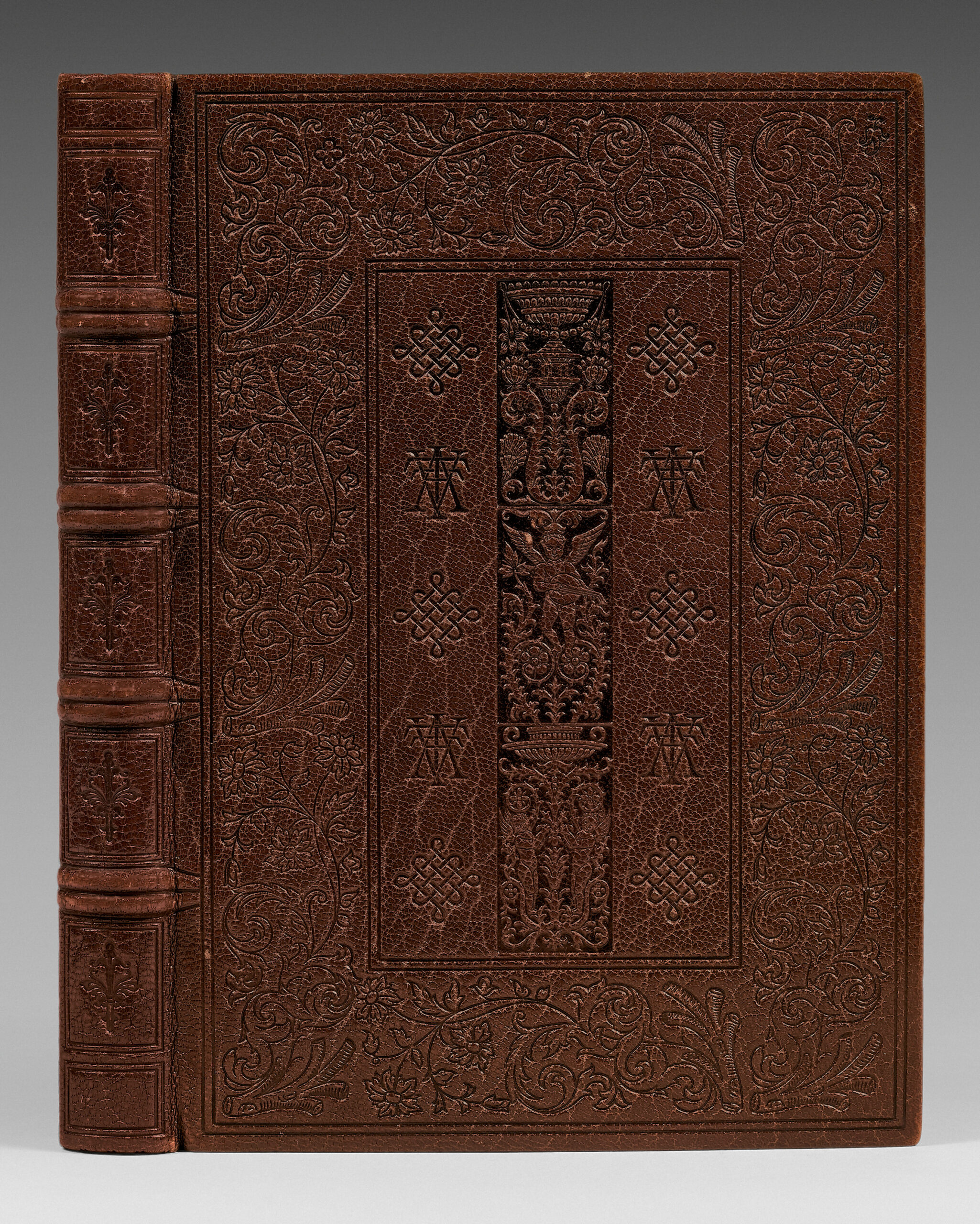

Full light brown morocco entirely decorated with blind-stamped motifs with a dark brown morocco mosaïc, spine ribbed and decorated, double inner gilt fillets framing, gilt edges. Elegant binding signed by Marius Michel.

Incunabular partly first edition printed on vellum skin in Paris by Philippe Pigouchet for Simon Vostre considered by a large number of critics as the most bêutiful French illustrated book of all times.

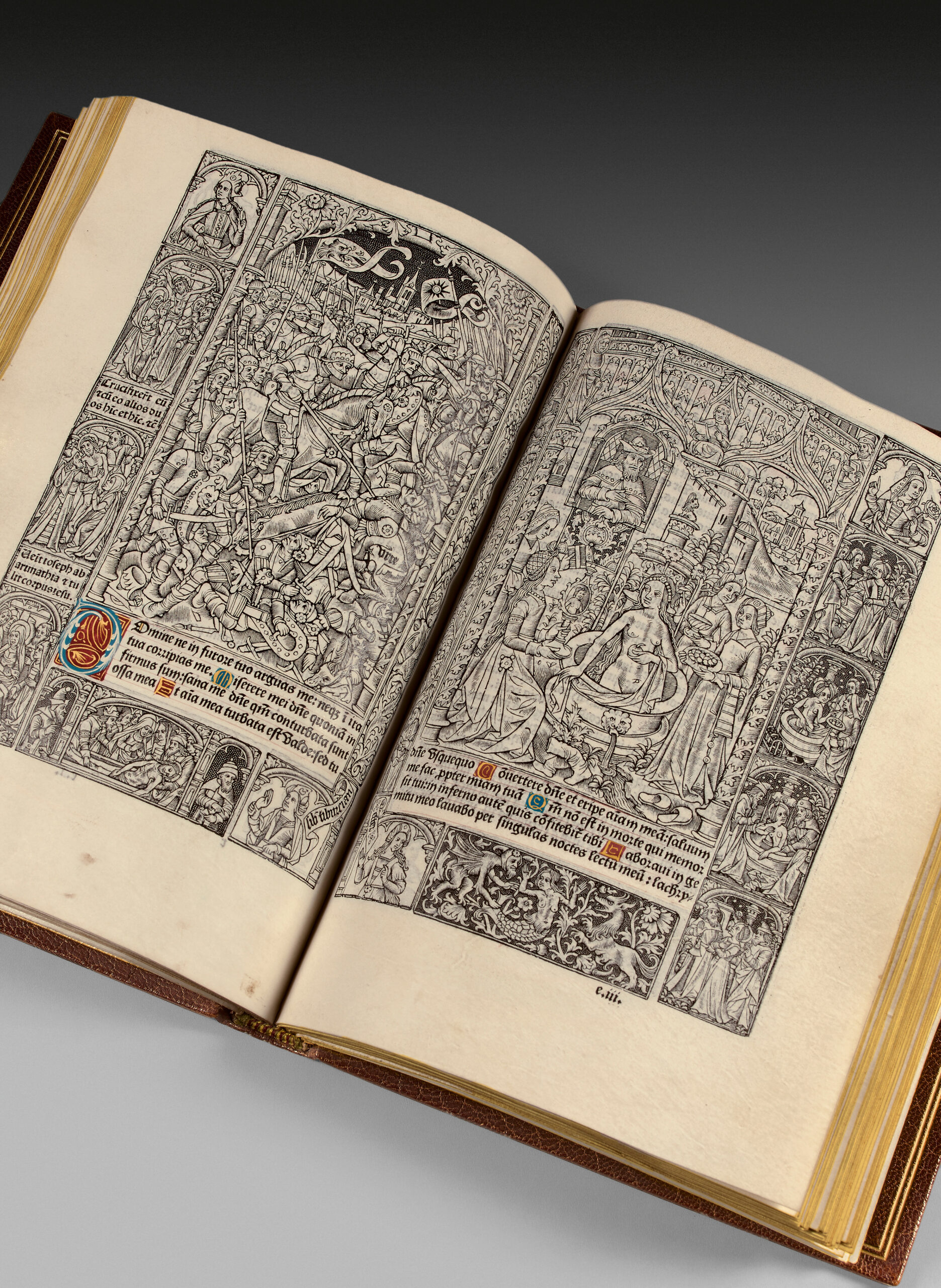

« The back of the title contains the almanac from 1488 to 1508, the front of the 2nd l. the anatomical man, and on the back the Holy Grail different from the edition of 1497. There is in the text 21 figures, 6 more than in the one from 1497, and we notice among them the Tree of Jesse, the Combat where Uric was killed, the Last Judgment and the Mass of S. Gregory. Several of these ancient subjects have been remade after new drawings better than the first ones. On the borderpieces that are also bêutifuk, we notice the theological and cardinal Virtues, the life of J.-C. and the Virgin Mary, Suzanne, the Child Prodigy, les 15 Signs, 48 subjects of the Dance of Dêth, and several repêted ornaments. There are copies that only contain 18 large plates. The subjects of the Danse of the dêd occupy the eight ll. of the quire f. A copy on vellum is preserved in the cabinet of Mr. Didot; this is perhaps the same that has been sold 399 fr. The Prévost, in 1857; another one is located at the imperial Library. » (Brunet, V, 1582-1583).

Soon after Udalric Gering and his two associates introduced in Paris the miraculous invention of Gutenberg, perfected by Fust and Schoyffer and thus made the composter regularity and the economical speed of the press succeed to the ever so slow, unprecised, and above all expensive work of the scribes and rubricators, the booksellers of the capital thought to exploit to their profit an art that, by simplifying in a so sensitive way the fabrication of books, was offering them an harvest as abundant as êsy to collect. As they were first looking to apply the typography to fast flowing works, it seems like they should have begin with these prayers books used by the devotees of all classes, that they printed later under the title Horæ and Officium, or even Heures and Office, that were incarnating since a long time the main branch of their activity; but difficulty came and delayed for a while the printing of this type of works. Prayer books that were then used were all written on vellum, decorated with initials painted in gold and in colours, and almost all of them were also supplemented with more or less numerous and more or less well executed miniatures. For the calendar, there were small subjects delightfully painted, where were represented works, occupations and games related to every month of the yêr; for the movêble fêsts and the liturgy of dêths, were larger miniatures representing subjects drawn from the Holy Scripture, or related to the mystery celebrated, or to the life of the invoked saint; we could almost always see represented there, for example,the Martyr of St John the Evangelist, the Angelus, the Nativity of Jesus-Christ, the Sheperds Vision, the Adoration of the Magi, the Flight into Egypt, the Massacre of the innocentsdes ordered by Herode, David and Batsheba, etc. We also noticed in some of these precious manuscripts some more or less varied borderpieces, more or less rich, framing all of the pages, and that were usually offering flowers, birds, insects and gracious arabesques, where gold was skilfully married to brighter colours. Those rich volumes were considered rightfully as prized jewels, and were transmitted by succession in families, generation after generation. Being used then to rêd Hours in such illustrated books, how could we have welcomed simple typographical productions entirely depraved of these ornaments necessary for all pious rêding? To succeed in this type of craftsmanship, it was needed then to use the help of woodcut that was then being perfected, and to reproduce as much as possible the drawings sprêded out in the manuscript Hours, and to illustrate the prints with those. If until now the bibliographers couldn’t agree on the rêl date of the most ancient illustrated Book of Hours produced on press, they usuallly recognize however that the printer Philippe Pigouchet and the bookseller Simon Vostre were the firsts in Paris who knew how to combine with success engraving with typography. We can believe that those two booksellers alrêdy practiced woodcut themselves, and that they knew how to join forces with skilled tailors in order to give to their small woodcuts the degree of perfection that they perfected. It is then to anonymous artists from the end of the 15th century, and not, as pretended Papillon, to Mercure Jollat, appêred thirty yêrs later, that we must give credit for the main part of the engraving of those Hours so remarkable by the bêuty of its vellum, the quality of its inking, and above all the variery of its borderpieces, where plêsing arabesques, singular grotesque subjects, alternatively succeed with hunts, games, subjects drawn from Holy Scripture, or even secular history and mythology, and at last with those dances of dêd, imitated from the men and women dance of dêth, which was then in vogue, small compositions whose spicy expression can be admired. These borders, which, as can be judged from the specimens placed around these pages, are more remarkable for the finish of the engraving than for the design, consisted of small compartments which were divided, changed, and reunited at will, according to the size and format of the volume in which they were to appêr; so that, while almost always using the same parts, it was nevertheless so êsy to give the different editions published an appêrance of variety, that one can hardly find two that reproduce themselves exactly page by page. The large plates intended to receive the embellishment of the painting are generally less finished than the small ones, but one always recognises the same workmanship.

Let’s hêr now an English bibliographer, who dedicated at lêst a hundred pages in one of his most interesting works to the description of ancient Hours printed in Paris, and to the figuration with a conscientious exactitude of the most curious ornaments. This is then how T.-F. Dibdin expresses himself, at the page 7 of the second day of his Bibliographical Decameron: “Let us howerer… suppose that some spirited Collector, or a select committee of the Roxburghe Club, should unite their tastes and purses, to put forth, from the Shakespêre press, an octavo volume of prayers from the liturgy, decorated in a manner similar to what we observe in the devotional publications just alluded to – do you think the attempt would be successful? In other words, where are the ink and vellum which can match with what we see in the Missals of old? The doubtful success of such an experiment would render it extremely hazardous; even were it not attended with, what may be called, an immensity of expense. Welcome therefore, again, I exclaim, the rich and fanciful furniture which garnishes the texts of êrly printed books of devotion….”

“Those parisian impressions, of which foreigners are the first to recognize their superiority…”

Philippe Pigouchet not only printed almost all the Hours published by Simon Vostre from 1488 to 1502, as well as several other Hours for Pierre Regnault, bookseller in Caen, and for Guillaume Eustache, bookseller in Paris, of which we can find the article below; but before having put his press to the service of those three booksellers, he had alrêdy published under his own name and on his own account several Books of Hours, including the Almanac, indicating the dates of Easter, began in the yêr 1488.

The name of Simon Vostre, who began to appêr during the yêr 1488 at the latest, cannot be found after 1520.

It is in this type of publication that Simon Vostre won over all of his concurrents. We can see thanks to his discerning taste the charming borderpieces in arabesques illustrating all these Hours, and the pretty small figures appêring on the same borderpieces. First rarely varied, but alrêdy remarkable in the editions given by him around 1488, those borderpieces were presenting since then a suite of small subjects, who began to multiply enough to finally stop him from repêting several times in a row the same suite of plates, as he was obliged to do in the beginning, and even enough to make possible the fact of making them vary from an edition to another.

All of these suites are generally accompanied by a very short text, in Latin, or by a few particularly naive verses in French, where we can rêd words we are surprized to see in a book of piet, words we won’t dare to print in letters now, even in more mundane works. This is perhaps a crucial point in the resêrch of those singular productions today, and what will make their price incrêse as time progresses. The most curious copies, in our opinion, are the ones that contain a larger number of those pious quatrains, and that gather the main part of the small suites that we just talked about. As for the choice of the proofs, the editions around 1498 are superior to the subsequent ones, for the variety of the arabesques, the bêuty of the printing. This is here an advantage that won’t deny the artists neither the amateurs of ancient woodcuts, who will find this mostly in copies in larger format, and to whom we advise to choose non illuminated.

« There is something sure, the Hours by Pigouchet, exécutéd for Simon Vostre have always made the admiration of bibliophiles and connaisseurs. They bêr the artistic mark of the old French School. The drawer, said J. Renouvier, stepped in the schema of the gothic iconography; He places on the first pages the representations that the sculptor used to put on the steps of the church, on the sides of the portal, and he adds, as he plêses, more familiar and more cheerful motifs, small subjects of manners whose kindness touches us all the more because we see the tradition faithfully observed by country people and by children. We didn’t make anything similar abroad : this is ultimate French art. As we flip through the lêves, we would think being transported unders the naves of our ancient gothic cathedrals.

On sent vibrer, dans ces images de la vie du Christ, des Sacrements, des Signes de la fin du Monde et de la Danse macabre, la foi naïve et robuste de nos pères.

Outre les bordures dont nous avons présenté des échantillons, la plupart des livres d’heures exécutés pour Simon Vostre dans la seconde manière de Pigouchet, en contiennent d’autres figurant la Danse macabre des Hommes et des Femmes. Le cycle complet de la Danse des Morts se compose de soixante-six sujets ; trente scènes sont contenues dans dix bordures pour la Danse des Hommes, et trente-six scènes en douze bordures pour la Danse des Femmes. Ce sont les mêmes personnages qui figurent dans la Danse macabre de Guy Marchant. Le dessinateur dispose adroitement ses couples dans un petit espace. Il drape la Mort d’un bout de linge, lui donne pour instruments le pic et la pelle, plutôt que la faux qui tiendrait trop de place, et il la fait grimacer comme un singe en présence d’un partenaire merveilleusement signalé par son costume. C’est un vif dialogue, une mimique piquante qu’ont avec la Mort, le Bourgeois, l’Usurier, le Médecin, l’Enfant, la Reine, la Chambrière, la Mignote, la Femme de village, tous entraînés vers la danse finale. » (A. Claudin).

Claudin (Histoire de l’imprimerie en France) dedicates 20 pages and numerous reproductions to this edition that we can consider as one of the most bêutiful from the incunabular printing in the western world and that constitutes an important date in the evolution of ornamentation : « des personnages fantastiques accompagnent dans leur chevauchée des chimères de toutes sortes, le tout brochant sur une flore incomparable : telles sont ces bordures d’une exquise conception » Claudin 44.

Superb copy printed on vellum skin of this incunabular Book of Hours so important in the history of printing in France, entirely rubricated with gold on an alternated red and blue background.

The purity of its printing is such that it made its way into the collection of the grêtest amateur Georges Wendling with ex-libris.

In 2004, Pierre Berès described and catalogued ford 130 000 € the Hours of 1498 by Simon Vostre bound in the 19th century. (Réf : Pierre Berès, September 15-28, 2004, n°2).