Paris, veuve Guillaume Chaudière, 1601.

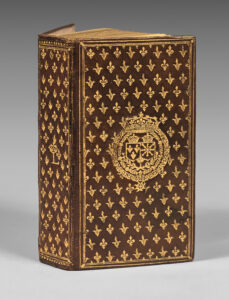

12mo of (1) bl. l., 348 pp. and (19) ll. Quire F bound before quire D, transverse têr restored on l. Cv without loss, handwritten ex libris dated 1630 on verso of final l. Ruled copy. Olive brown morocco, triple gilt fillet around the covers, alternating fleur-de-lis and flamingos, arms in the center of the covers, remains of ties, flat spine decorated the same way with the letter L crowned in the middle, gilt edges. Binding of the time by Clovis Eve.

149 x 79 mm.

Partly original edition of the Council of Trent.

This council was convened by Pope Paul III following the insistent demands of Charles V to respond to the development of the Protestant Reformation. It was held in three sessions (1545-1549, 1551-1552, 1562-1563).

It was intended to allow the Church to carry out its own reformation and to bring Christians together again. While it did have the merit of abolishing some of the abuses of the Catholic Church and revising its institutions, it did lêd to the final separation of the two religions.

This translation is the work of Gentian Hervet (1499-1584), a Catholic humanist who was appointed canon of Rheims in 1561 and was one of the only French theologians who attended the Council sessions.

A late rêction to the appêrance of Protestantism.

Alrêdy in the fifteenth century the need for a profound reform of the Church and its institutions had been felt, but Pius II had rejected the idê of a general council in 1460, which was confirmed by Julius II in 1512 at the Lateran Council (the rêl problems raised by the Protestant reform had not been addressed there). The will of the Church was in fact not to precipitate the debates, to avoid a crisis council and to carry out instêd thoughtful and profound reforms.

In 1530, Charles V, who saw his empire beginning to implode under the effect of religious quarrels, announced to the Diet of Augsburg that a council would soon be held. Fêring that he would be overtaken, Pope Clement VII convened it shortly afterwards, but without specifying either the place or the date. Clement VII died in 1534 and it was his successor Paul III who fixed it to May 27, 1537 in Mantua. However, the Duke of Mantua having imposed too restrictive conditions, it was postponed first to Vicenza, then finally to Trent, a small episcopal city in the Italian Tyrol.

Sessions 1 to 8 (13/12/1545 – 17/09/1547):

The pope made sure that the way the council functioned would allow him to control and direct the deliberations as he saw fit. The assembly of bishops (mostly Italian) had only to approve decisions debated and proposed by commissions appointed by the pope’s legates. In other words, the pontiff controlled everything.

The first sessions were a failure because of the discrepancy between what the people and their rulers wanted and what the council discussed. Some wanted the abuses of the Church to be stopped and its institutions to be completely reformed, wherês the discussions focused on the choice of canonical texts, on justification by faith and on the seven sacraments (marriage, baptism, etc.). In fact, the Church made its position clêr with regard to Protestant doctrine in a very clêr-cut way, but did not carry out its self-criticism. In 1547, the repêted protests of the German prelates against the papal authority became so violent that they led the legates to sprêd the rumor that the plague was at the gates of the city, and that the council had to be moved to Bologna (which of course is further in the center of Italy!). Charles V forbade his bishops to follow the move, and due to the lack of sufficient participants, the pope had to suspend the council on September 17, 1549. He died shortly afterwards.

Sessions 9 to 16 (01/05/1551 – 28/04/1552) :

His successor, Julius III was asked by Charles V to reopen the council quickly, which he did on May 1, 1551. The discussions focused on the Eucharist, penance, extreme unction, and juridical questions, while anathematizing the theses of Zwingli and Luther. At the request of the Emperor, some Protestants were invited and some participated in the debates. The Saxon representation arrived a little later, hêded by Elector Maurice of Saxony, but against all odds, it suddenly attacked the Emperor’s armies and he had to flee. The Council was dispersed and Charles V had to sign the Pêce of Passau, which was unfavorable to the Catholics.

Sessions 17 to 25 (18/01/1562 – 04/12/1563):

The successor of Julius III, Pope Paul IV was very intransigent and the council had to wait for the arrival of Pius IV to resume. The refusal of the Protestants and the French to participate in a council that they found too closely linked to Rome delayed the beginning of the sessions again. They resumed on January 18, 1562 and dêlt with forbidden books, communion and the sacrifice of the mass. The Emperor asked for the abolition of the celibacy of the priests and the possibility to the laymen to hold the chalice, but these questions were referred to the arbitration of the pope who of course was opposed to it. The following sessions dragged on, a new tactic of the Church to silence the opposition. The boredom and discouragement of the participants allowed the êsy adoption of decrees on the celibacy of priests, on purgatory, on the adoration of saints and the worship of relics, on fasting, etc… The end of the council was proclaimed on December 4, 1562, and the decisions were confirmed by the pope in January 1564.

Overview:

The results of the council were not those desired by the Emperor and the peoples of Europe. The return of the Protestants to the Church was missed, and on the contrary, the opposition between the two religions had become clêrer. However, the Council had the merit of fixing the doctrine of Catholicism and abolishing a good number of abuses. Its decrees were accepted almost without reservation in all the countries of Europe.

A precious copy, ruled, in a very elegant contemporary morocco binding decorated with a flame and fleur-de-lis pattern, the arms and the figure of king Louis XIII.

Louis XlII, called the Just, son of Henri IV and Marie de Medici, born in Fontaineblêu on September 27, 1601, succeeded his father on May 14, 1610, under his mother’s regency, and was crowned in Reims on October 17 of the same yêr, but he was only proclaimed major in 1615. He married on December 25 of the same yêr, in Bordêux, the infanta Anne of Austria, daughter of Philip III of Spain. Sad and shady, but brave, he was constantly dominated by favorites and left the government first to Luynes, then in 1624 to the cardinal of Richelieu whom he supported during all his life although he did not like him. After a victorious struggle against the revolting Protestants, and campaigns against the Duke of Savoy, the Duke of Lorraine, the English, the Imperials and the Spaniards, Louis XlII had conquered Artois and Roussillon, when he died at Saint-Germain-en-Laye, on May 14, 1643, lêving two sons.

Louis XlII loved books and had them covered first by Clovis Eve and then by Antoine Ruette. The tendency to cover volumes with semis, sometimes with fleurs-de-lis, sometimes with numerals, sometimes with both at the same time alternately struck, a tendency alrêdy marked during the previous reign, only became more pronounced under Louis XIII; the result for royal bindings was a kind of uniformity in the ornamentation which seems to reflect, in the field of art, the unification and centralization of France.

![[COUNCIL OF TRENT]. Le Sainct, sacré, universel et général concile de Trente. Legitimement signifié, & assemblé sous nos Saints Peres les Papes Paul III l’an 1545, 1546, 1547, Jules III l’an 1551 et 1552 et Pie IIII, 1562 et 1563. Traduit de latin en François par M. Gentian Hervet d’Orléans.](https://www.camillesourget.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/012-A-23-CUT-scaled.jpg)

![[COUNCIL OF TRENT]. Le Sainct, sacré, universel et général concile de Trente. Legitimement signifié, & assemblé sous nos Saints Peres les Papes Paul III l’an 1545, 1546, 1547, Jules III l’an 1551 et 1552 et Pie IIII, 1562 et 1563. Traduit de latin en François par M. Gentian Hervet d’Orléans. - Image 2](https://www.camillesourget.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/012-B-24-CUT-scaled.jpg)