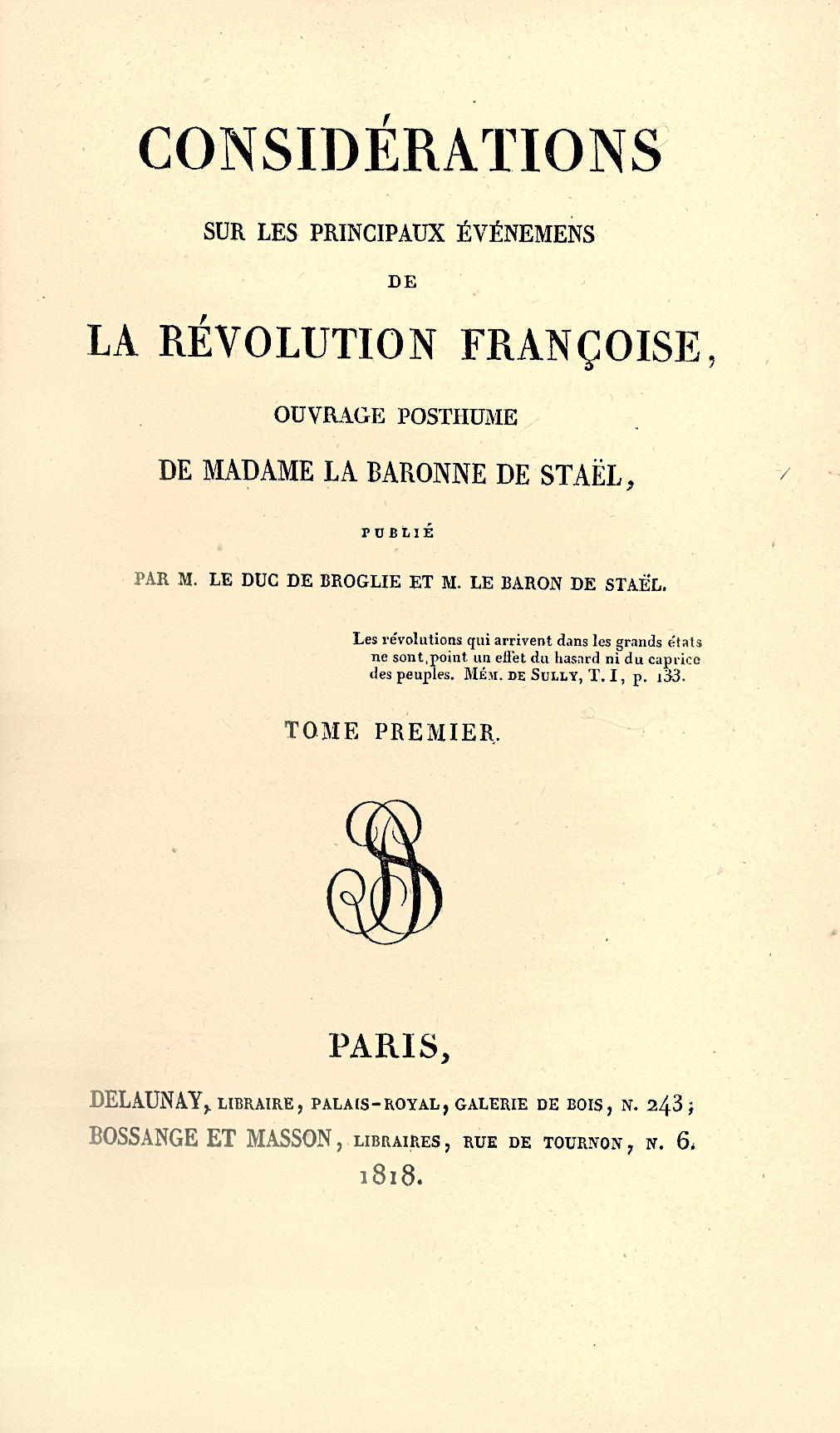

Paris, Delaunay, Bossange et Masson, 1818.

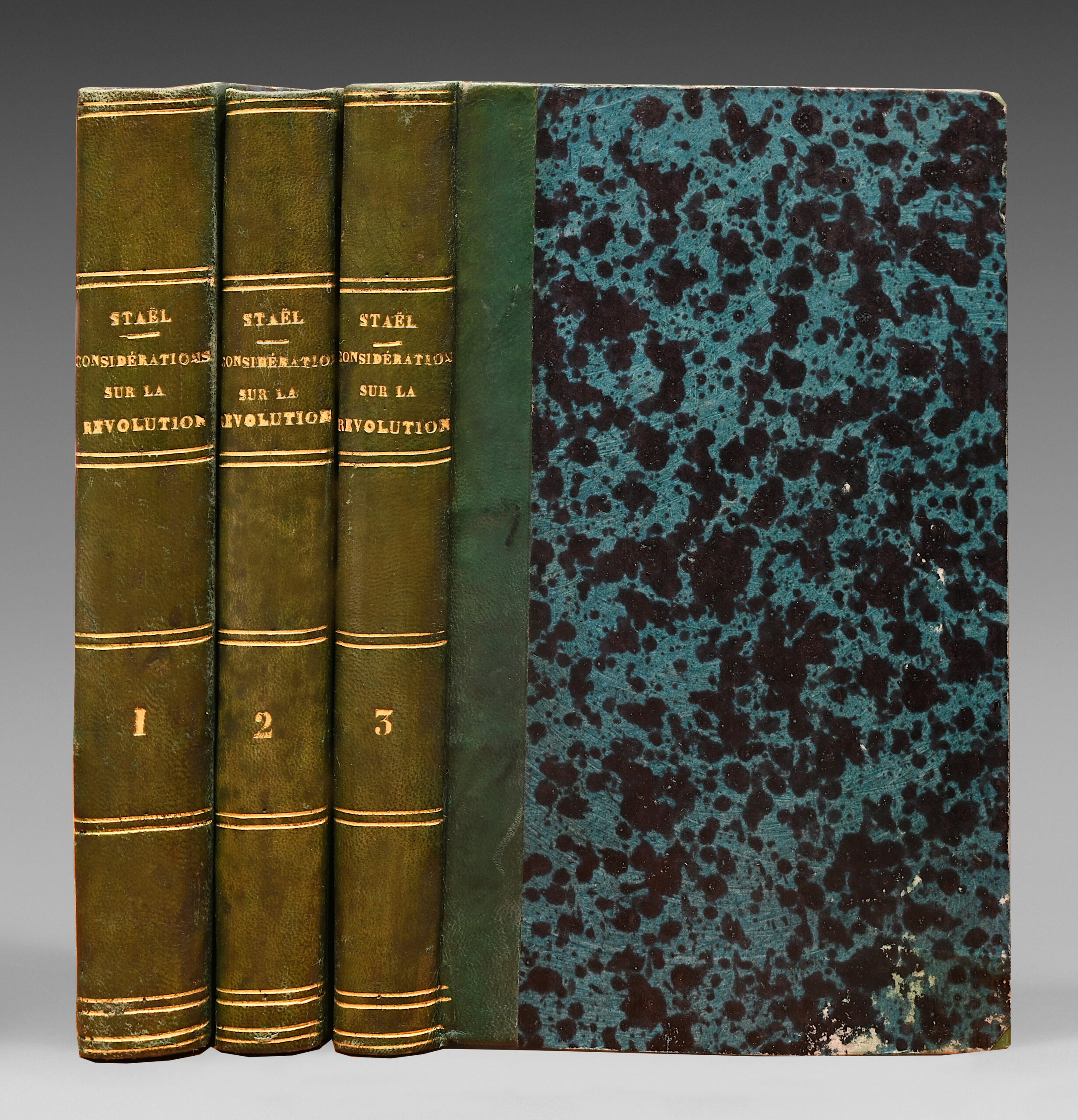

3 volumes 8vo of : I/ x pp.., 440 pp..; II/ (2) ll.., 424 pp; III/ (2) ll.., 395 pp, (1) l. of errata, (4) ll.. ads. Green half-sheepskin, flat spines decorated with gilt title and gilt fillets. Contemporary binding.

201 x 126 mm.

First edition of this famous book by Madame de Staël, endowed with great freedom of thought, which caused quite a stir.

Vicaire, VII, 654; Bulletin Morgand et Fatout, n°5898; Clouzot, 255; Lonchamp, 117-1; Martin & Walter, 31988; Tourneux, I, 114; En Français dans le texte, 222.

The work was published by Madame de Staël’s son and son-in-law, the Baron de Staël and the Duc de Broglie, based on the original manuscript completed by Madame de Staël in the early days of 1816.

A landmark essay: at the origin of the first great intellectual debate on the French Revolution.

Germaine de Staël (1766-1817) wrote almost all of her literary work during the repeated exiles she suffered as a result of her political and social liberalism, particularly with regard to the status of women. Napoleon, whom she initially admired and believed she could advise, again closed the borders of France to her in response to the political and “feminist” positions taken in her works. A woman of commitment, Madame de Staël, through her writings and the salons she held successively in Paris and in Coppet, on the shores of Lake Geneva, exercised a considerable intellectual influence not only on literature but also on the society of her time.

Initially, Madame de Staël intended to write a political eulogy of her father, the banker Jacques Necker (1732-1804), who had been Louis XVI’s Minister of Finance; but, going beyond her original subject, she studied the Revolution as a whole, its causes and consequences – the Napoleonic regime – and promoted, by comparison, the English system, which she regarded as the model of all democracy. In this way, she ended the whole of her work with an apology for the country she admired above all others.

These Considérations were enthusiastically received by the public, and over 50,000 copies were published, giving rise to lively debate and much criticism.

Madame de Staël is fashionable… The impetuous and turbulent Germaine would no doubt have been delighted. In recent years, numerous studies and reprints have attested to this revival. It has to be said that, among our neighbors in French-speaking Switzerland, as in all countries, among specialists in literature, and in particular in comparative literature, studies on Germaine de Staël born Necker, on her entourage and on the ideas and thinking of this woman and this man have never slowed down much.

For Madame de Staël’s work is a veritable ‘sum’ – partial, of course… – of the history of the entire period from Necker’s first ministry to the year before Germaine’s death in 1817. It is the history of the Revolution as seen through the lens of ideas, thoughts and action. Not only does it present the sum total of the hopes and ambitions of Madame de Staël, daughter of Necker, but also mistress of Narbonne, then, after the height of the revolution, mistress of Benjamin Constant and, more occasionally, of Talleyrand: only later, when Bonaparte scorned her advice and Napoleon disgraced her and confined her to the shores of Lake Geneva, did she resign herself to being no more than a distant dispenser of lofty considerations and to becoming a Cassandra with regard to the policies of the ‘tyrant’ who embodied France.

All in all, this book should be read and reread. For the historian, it naturally exceeds in interest all the other writings of Madame de Staël.

“This famous work established the liberal interpretation of the French Revolution by dissociating 1789, for the first time brazenly rehabilitated, from 1793” (Yvert, Politique libérale, n°24).

Precious copy in a contemporary binding from the “Bibliothèque du Château de Louppy”, owned by the Custine de Wiltz family.