Colophon: Impresso in Firenze per ser Francesco Bonaccorsi Nel anno mille quattrocento nouanta Adi. xx. di septembre (20 September 1490).

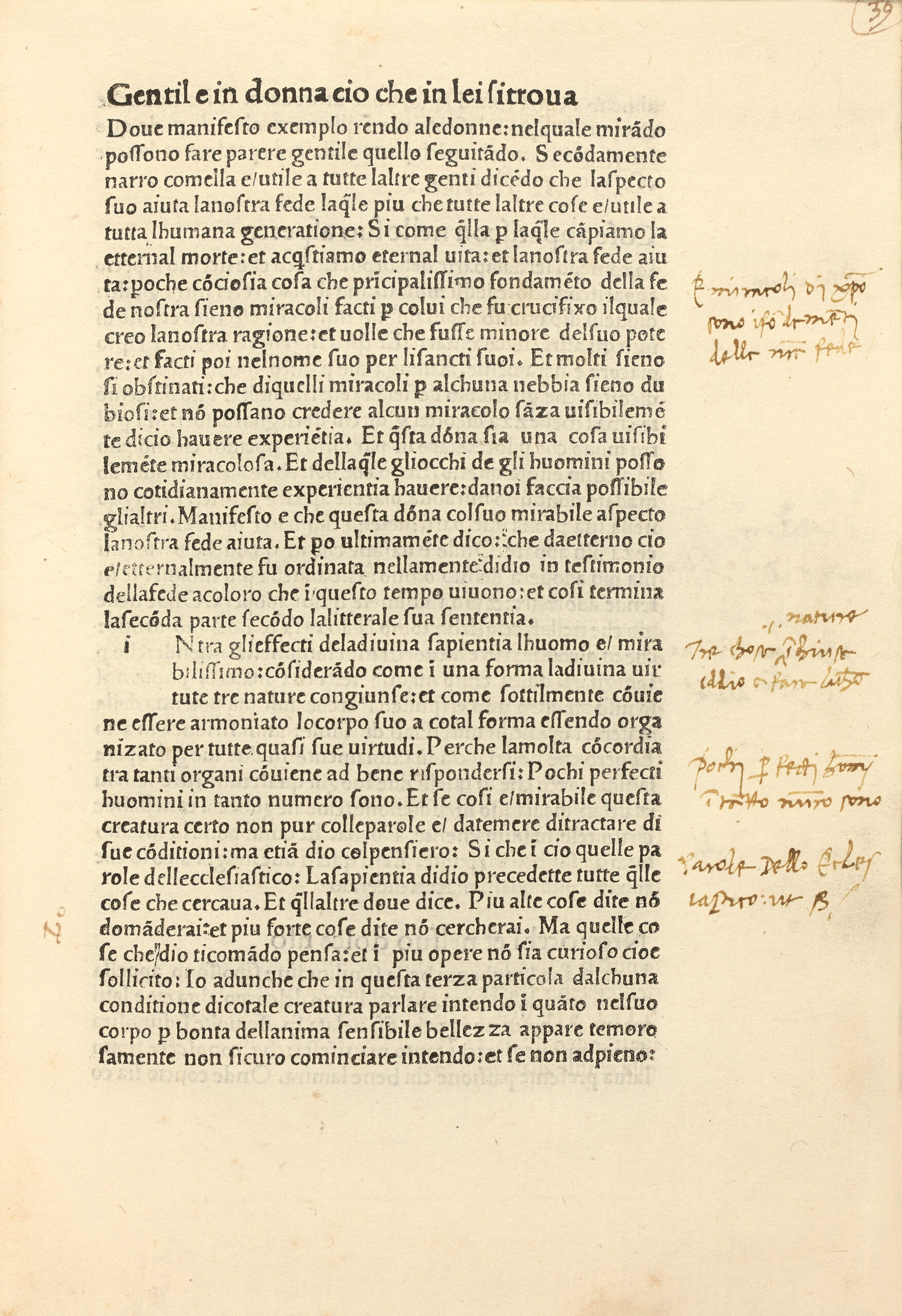

4to. A-k8-l10. 90 ll., 38 lines. Types: 112 R., text; 79 R., commentary.

Ivory vellum, flat spine with handwritten title, blue edges. 18th century Italian binding.

204 x 138 mm.

First edition of one of Dante’s masterpieces.

Hain 5954.

Written in Italian during his exile between 1304 and 1307, the Convivio – The Feast – is probably the most direct work in which Dante sets forth the general philosophic problematic that drives him. This treatise was aimed to contain all human knowledge. Indeed, it contains questions of politics, philosophy and love.

Dante was the first to defend the use of the vernacular language, which he considered superior to Latin in terms of beauty and nobility of language. “The first extended piece of original expository prose in the Italian vernacular” (Lansing, Dante, encyclopedia, pp. 224-232).

The three fundamental themes of the Convivio are the defense of the vernacular, the exaltation of philosophy, and the debate on the essence of nobility.

The Feast was born of the need felt by Dante to defend his reputation in the eyes of those with whom he had contact and to reveal himself as he really was, a lover of wisdom, a man of moral integrity. Also driven by the desire to expose his doctrine he will comment on his love of wisdom he understands by wisdom, the knowledge that is conquered by the knowledge of the truth. Of this wisdom, supreme perfection towards which every man tends by an interior impulse, Dante will make a feast, not because he is among the “few privileged ones who sit at the table where the bread of the angels [wisdom] is eaten”, but because, having “escaped from the appetites of the vulgar, he finds himself at the feet of those who sit”. He gathers “what is due to them”, and he tastes the sweetness of it, knowing the miserable life of those who have remained fasting because of their “family and civil” occupations. Guided by this feeling, he is incited to write for all those, “princes, barons, knights and other nobles, men and women, who are part of the people and who have other concerns than that of literature. The social well-being depends on them, that is why it is necessary to instruct them in their own language, that of every day, forsaken by the literates of profession, only concerned with their gain. To those who have preserved their natural wisdom, Dante will offer his teaching in songs to which he will bring all his care and all the experience of his maturity. These songs will be the “food” of the feast, the “bread” will be the commentary in running prose. In these prose statements Dante will not use Latin (“bread of wheat”) so that the relationships, the correspondences that must necessarily exist between the commentary and the songs in the vulgar language are not broken. He will use the common language (“barley bread”) because universally understood it will spread science and virtue (wisdom) more widely. He is also influenced by the natural love which binds him to the language which is his since his birth, and in which palpitates the life of his thought and spreads the sensitive waves of his first affections. With the enthusiasm of the artist who exalts himself by celebrating his own language, because he feels it to be a docile instrument of lively, original, warm expression, Dante affirms the “value” of vulgar Italian, capable of expressing “very great and very new concepts in a suitable, sufficient and satisfactory way”, just like Latin. He attacks with a generous disdain the “bad Italians who praise the vulgar language of the others, but who depreciate that which they speak”. This language is henceforth dedicated to the needs of the future, it will be “the new light and the new sun which will rise where the old one [Latin] will have disappeared, and it will spread its light on those who are in darkness and obscurity”. Dante concludes the introduction with his confidence in the future triumph of vulgar Italian and in the intrinsic value of his work.

The moralist Dante who will judge men in The Divine Comedy is already fully present in The Feast. The guidelines of his thought, which faithfully bends to all the requirements of reality, are clearly outlined in this work, in spite of the abundance and obscurity of additional notes and marginal digressions. They harmonize between them within the limits of a system of rational principles, rigorously deduced, by means of syllogisms. It results from it a robust and severe prose, very far from the fragile lightness of the Vita nuova. This prose is not exempt from a certain roughness in the complex structure of the syntax, but the guiding thought brings it, without any concession, but by easy effects, until the expression of this wisdom of which the soul is thirsty. This same wisdom which, in The Divine Comedy, will be embodied in the character of Virgil, is a philosophical wisdom thanks to its objective value, but such as it finds in the faith a light which strengthens it and which gives a new savor to the truths of the reason. It is, however, a wisdom that quenches but does not quench, because it aspires to know the superior wisdom that is denied to the temporal world. Dante had made of these states a living and personal experience that he expresses in a poetic way. And by his own admission, he attributes the perfect craftsmanship of these philosophical songs to the influence of Virgil, “his master”.

a precious and beautiful copy preserved in its attractive 18th century vellum, with the margins covered with old notes and comments in ink.