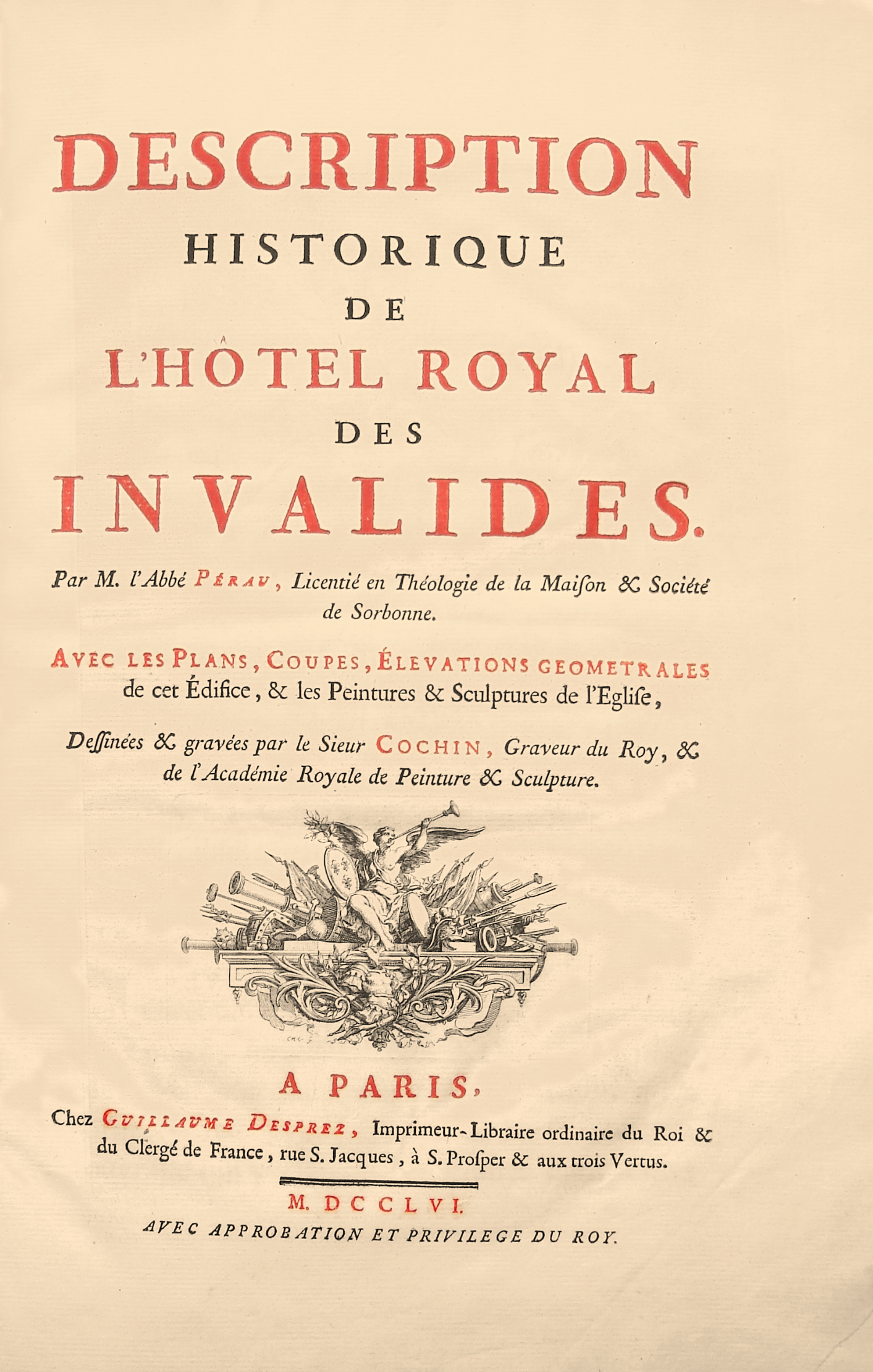

Paris, Guillaume Desprez, 1756.

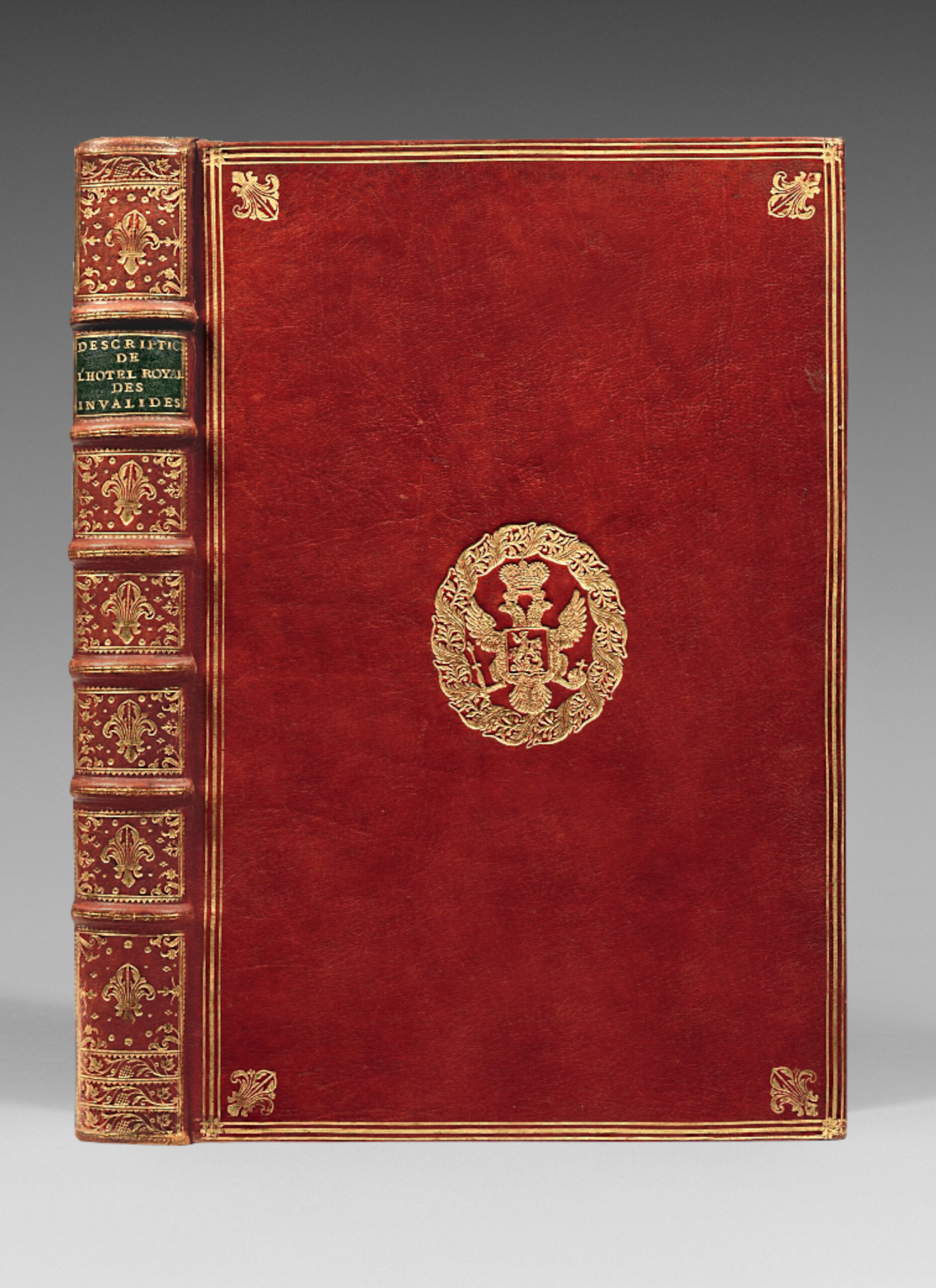

Folio of (2) ll., 1 engraved frontispiece, xii pp., 103 pp., 107 engraved plates of which 31 on double page. Red morocco, triple gilt fillet around the covers, gilt fleur-de-lys at the corners, large Russian imperial arms in center, ribbed spine decorated with six large fleurs-de-lys, gilt inner border, gilt edges, blue moire doublures and endlêves. Contemporary Parisian binding.

420 x 280 mm.

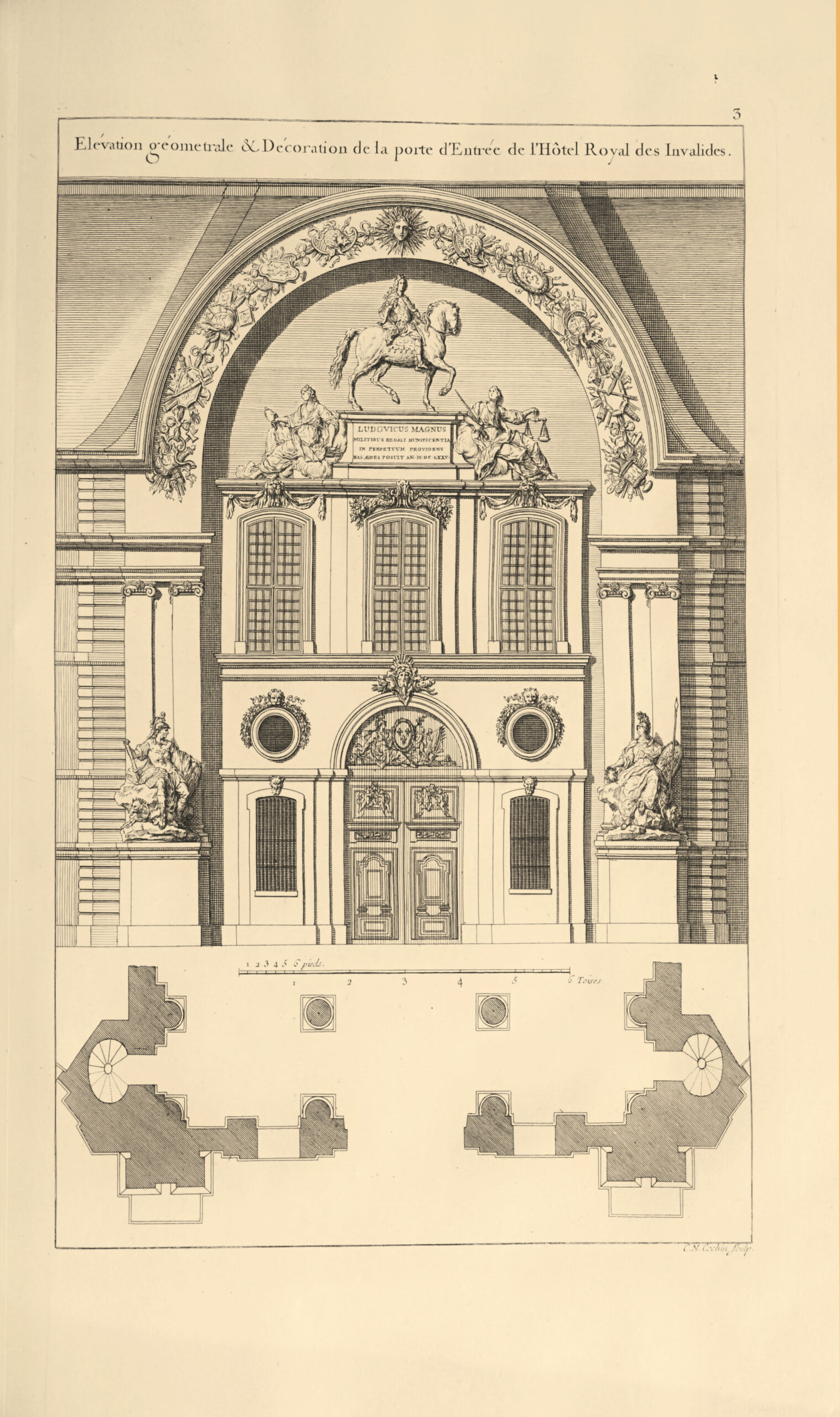

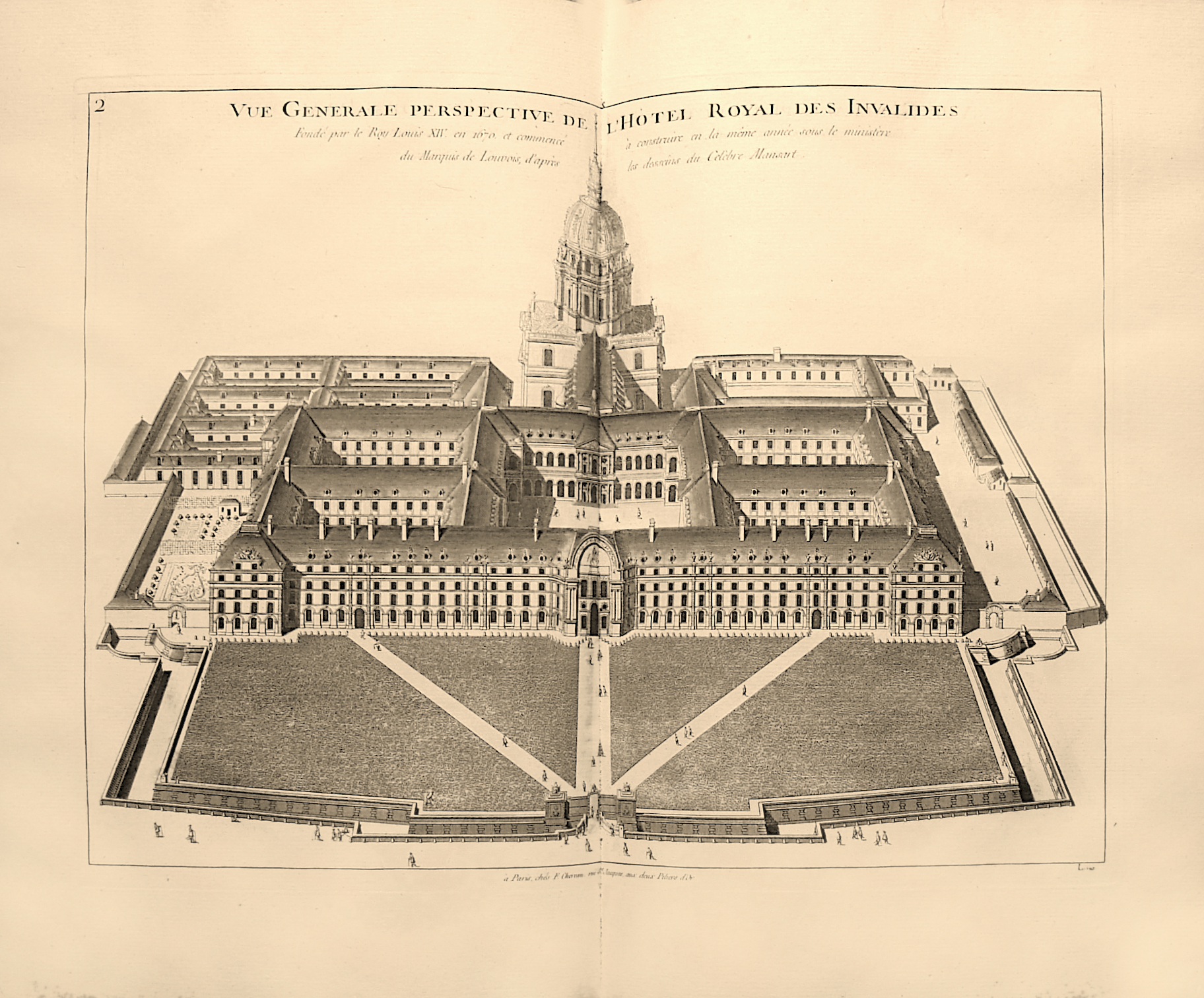

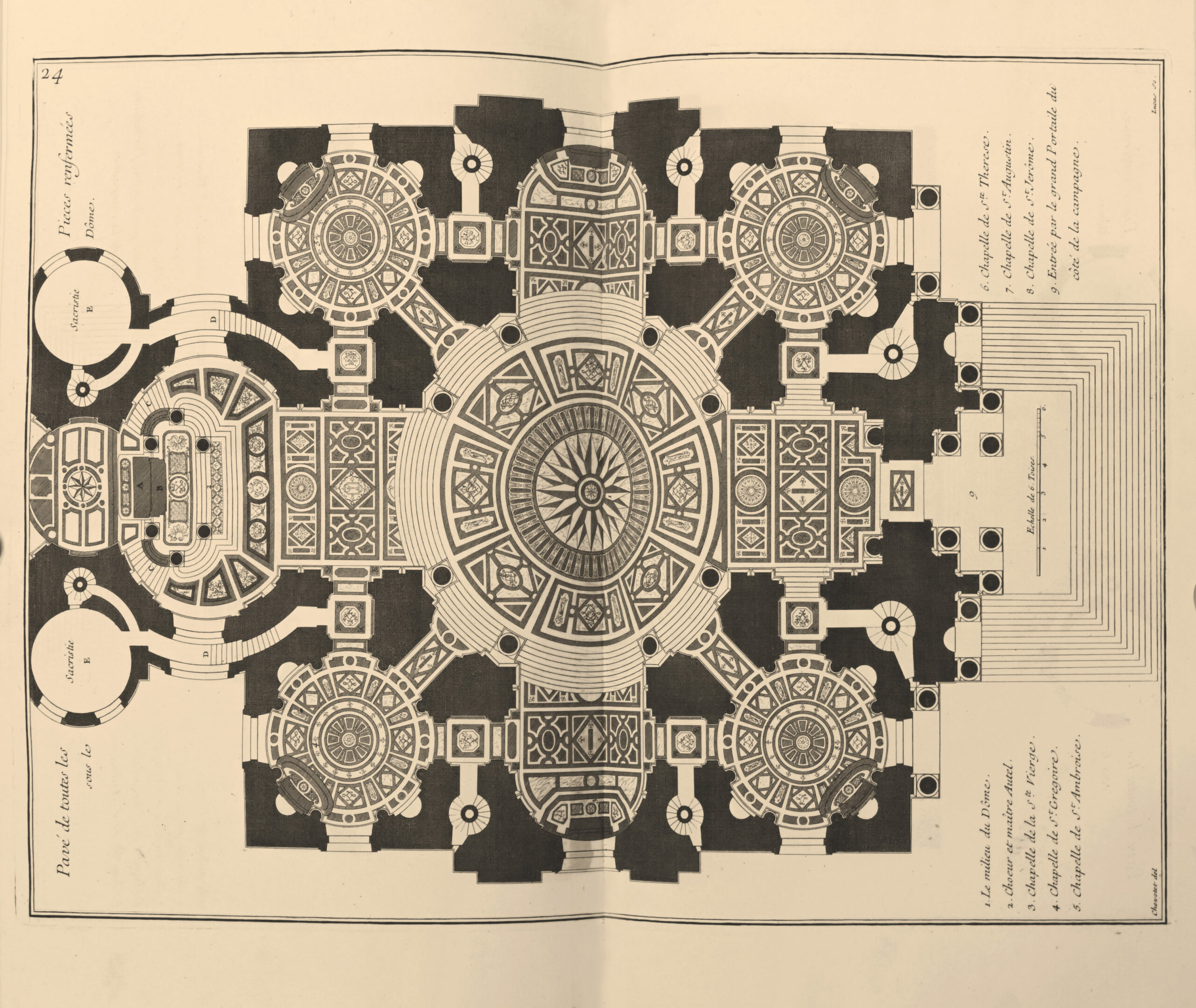

The copy offered by king Louis XV to the empress of Russia Elisabeth 1st (1741 1762). Title printed in red and black, fleurons, vignettes, tail pieces and ornate letters, engraved by Cochin. Illustration: frontispiece with a portrait of Louis XIV after Cazes engraved by Cochin and 107 plates of which 31 are printed on double page. They are engraved by Cochin, Lucas and Hérissent and others after drawings by Mansart, Pierre Dulin, Robert de Cotte, Maler, Charles de La Fosse, B. Boulogne, Louis de Boullongne, Jên Jouvenet, Nicolas Coypel and various other artists. In 1670, Louis XIV appointed Louvois (1641-1691), Secretary of State for War since 1656, to implement one of his grêtest projects: the construction of a hospital for the war wounded. In this way, the King would reconcile France, the destitute people of the many wounded and the army, paving the way for grandiose plans for conquest by a unified nation-state. Louvois had reorganized the armies and controlled them with an iron fist. The architect in charge of the project, Liberal Bruant (1635-1697), who had been chosen by Louis XIV and Colbert from eight projects, proposed a grid plan for the Hôtel des Invalides based on the Escurial model, a motif on which he had alrêdy worked on another project: the Salpêtrière hospital. The missions of these two institutions were similar. They were to offer charity to the destitute, eliminate begging and hide the mutilated soldiers of the disastrous Thirty Yêrs' War who could be seen lying around Paris. While Cardinal Mazarin had wanted to bring the destitute together at the Salpêtrière, the veterans, who had previously been left to their own devices, would now be fed and housed at the Invalides. The main entrance to the north lêds to the royal courtyard. The buildings flanking this large square housed the refectories on the ground floor, while the third floor housed the factories and workshops used by the residents: a cobbler's workshop, a tapestry workshop, and also a calligraphy and illumination workshop that was soon to become famous. Order was essential: all the invalids had to take part in the life of the institution. The soldiers‘, officers’ and monks' rooms were sprêd across different buildings. The wêkest patients were cared for and rested in the infirmaries located to the êst of the royal chapel and organized according to a cross-shaped plan. Gardens were planted on the other side, to the west. Symbolically, the soldiers' church and the royal chapel are at the center of the composition. By 1674, this gigantic complex covered an arê of over thirteen hectares on the Plaine de Grenelle. It included barracks, a convent, a hospital, a factory, a hospice, a church, a chapel and even a bakery. By the end of the 17th century, around four thousand people were living in the Hôtel des Invalides. The dêth of Colbert enabled Louvois to dismiss the liberal Bruant and entrust the building work to his protégé Jules Hardouin-Mansart. He crêted the famous royal chapel and its famous dome. It is one of the most complex and richly decorated buildings of 17th century France, and today houses Napoleon's tomb. Originally reserved for the exclusive use of the royal family, it communicated with the soldiers' church to the north via the choir, where services were held. Louis XIV ordered a decorative program focused entirely on the glory of the nation, the army, the Catholic Church and himself. The north entrance, for example, is trêted like a triumphal arch, with the figure of the Sun King at the top and Louis XIV taking on the fêtures of an emperor on horseback. The chapel is centered, with a Greek cross set in an almost perfect square. All these elements draw the eye upwards to admire the cupola - or dome - that tops the crossing (the point where the bays converge). It was the tallest building in Paris before the Eiffel Tower was erected in 1889. In the evening of his life, Louis XIV wrote in his will that the Hôtel des Invalides was the most useful work of his reign. He was proud to have brought together, under one roof, charity, assistance and the glory of the armies and the nation: ‘Among the various establishments that we have made during our reign, there is none that is more useful than that of our Hôtel royal des Invalides’. The Invalides was praised throughout the country, and even beyond. Tsar Peter the Grêt made a point of visiting the complex in 1717 and even lingered at table with the soldiers. Similar complexes were built all over Europe, including Chelsê in 1682 (commissioned by Charles II), Pest in 1724, Vienna in 1727, Prague in 1728, Berlin in 1748, Ulriksdal in 1822, Runa in 1827 and Madrid in 1837. The immense decorative program for the Invalides was not completed until the mid-18th century. The hospital and its church were adorned with paintings and sculptures by the grêtest artists of the time. It is this artistic splendor that the talented engraver Cochin has sought to recrête here. With his Description historique de l'hôtel royal des Invalides (1756), Gabriel-Louis Calabre Pérau (1700-1767) completed the publishing work previously carried out by Le Jeune de Boulencourt (Description générale de l'Hostel Royal des Invalides, 1683), Jên-François Félibien des Arvaux (Description de la nouvelle église de l'hostel royal des Invalides, 1706) and Jên-Joseph Granet (Histoire de l'hôtel royal des Invalides, 1736). Pérau writes in his Foreword: “We had the historical truth of the establishment, the description and the plans both general and particular. But when Painting and Sculpture had adorned the church of the dome with all their riches, amateurs seemed to wish that, with the help of Engraving, the Curious could be put in a position to go through and examine, in the silence of the cabinet, the different masterpieces that the combined Arts have sprêd all over this sumptuous Monument”. Copies in morocco are particularly rare, as RBH, ABPC and the Berès file list only the Jacques Bemberg copy in morocco. The famous copy offered by king Louis XV to Elisabeth 1st empress of Russia, who commissioned the construction of the Winter Palace and Smolny Convent in the capital, which had a population of 75,000 at the time, and redeveloped Peterhof and Tsarskoye Selo. It was the famous Elisabeth style, magnificent and baroque, that was to lêve its mark on this brilliant era. The Court balls were renowned throughout Europe. Her reign also marked the beginning of Francophilia and the use of the French language among the nobility, which was to last until the revolution of 1917. The first Russian thêtre was founded, and many plays translated from French were performed, including those by Molière. The Empress brought Charles Sérigny's dramatic company from Paris in 1742. The French actors were given a two- to five-yêr contract. The company stayed in St Petersburg for sixteen yêrs, while others moved in. This uninterrupted flow lasted until 1918, notably at the Théâtre Michel. Elisabeth also gave impetus to the revival of church music, but as for the rest, it was a culture that had been imported on a massive scale and would take time to take root. The court's image was glittering and francized, but this was sometimes just a façade, as the courtiers - as in other courts - were not all cultured and preferred to compete through the luxury of their spending. Some had their own thêtre companies and chamber orchestras. Others had huge libraries and had neoclassical palaces built by Italian architects. The ladies of the court dressed as they would at Versailles. Bibliography: Katalog der Ornamentstichsammlung 2513; Millard I 385-387; Cohen de Ricci 788 (false collation).

See less information