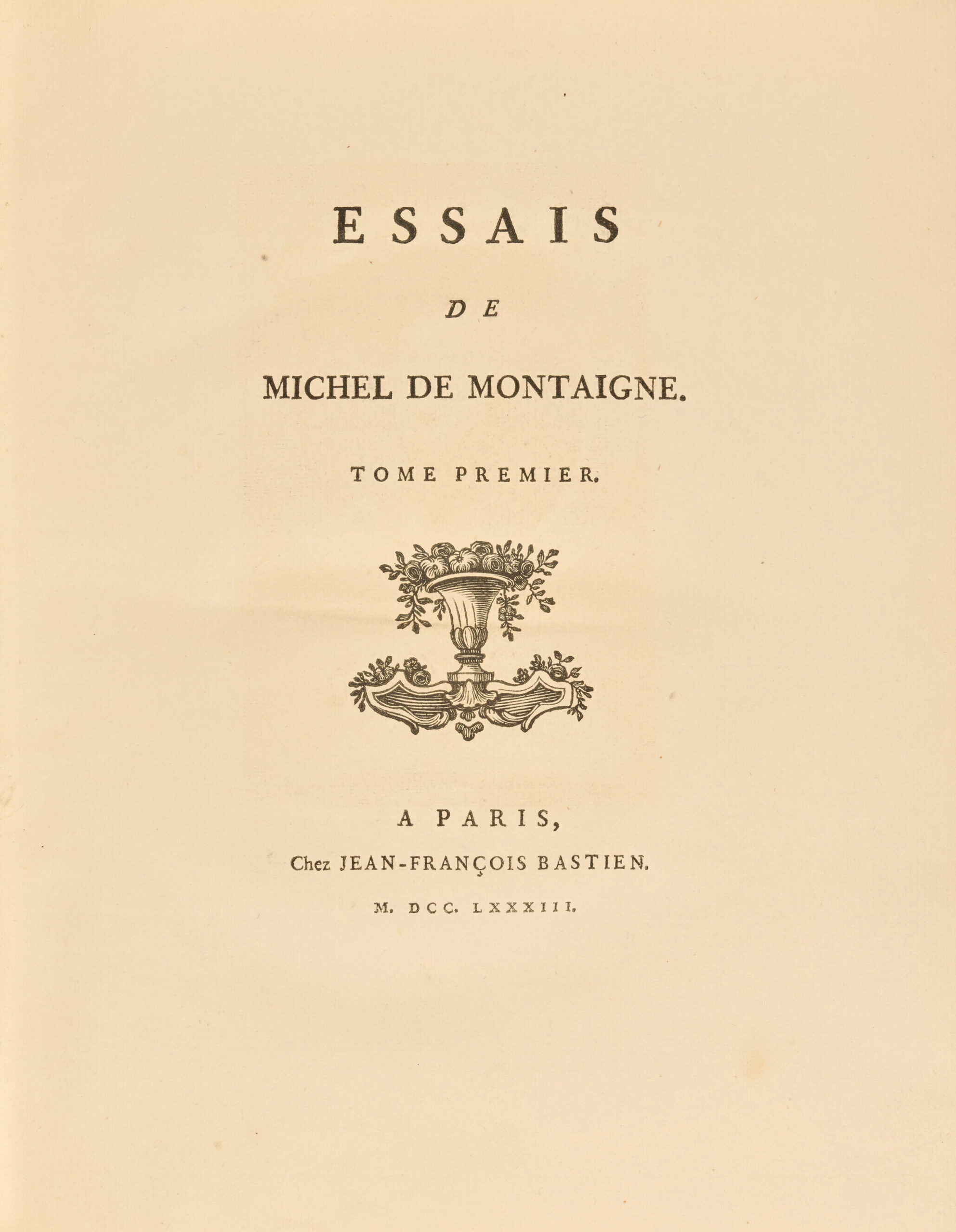

Paris, Jean-François Bastien, 1783.

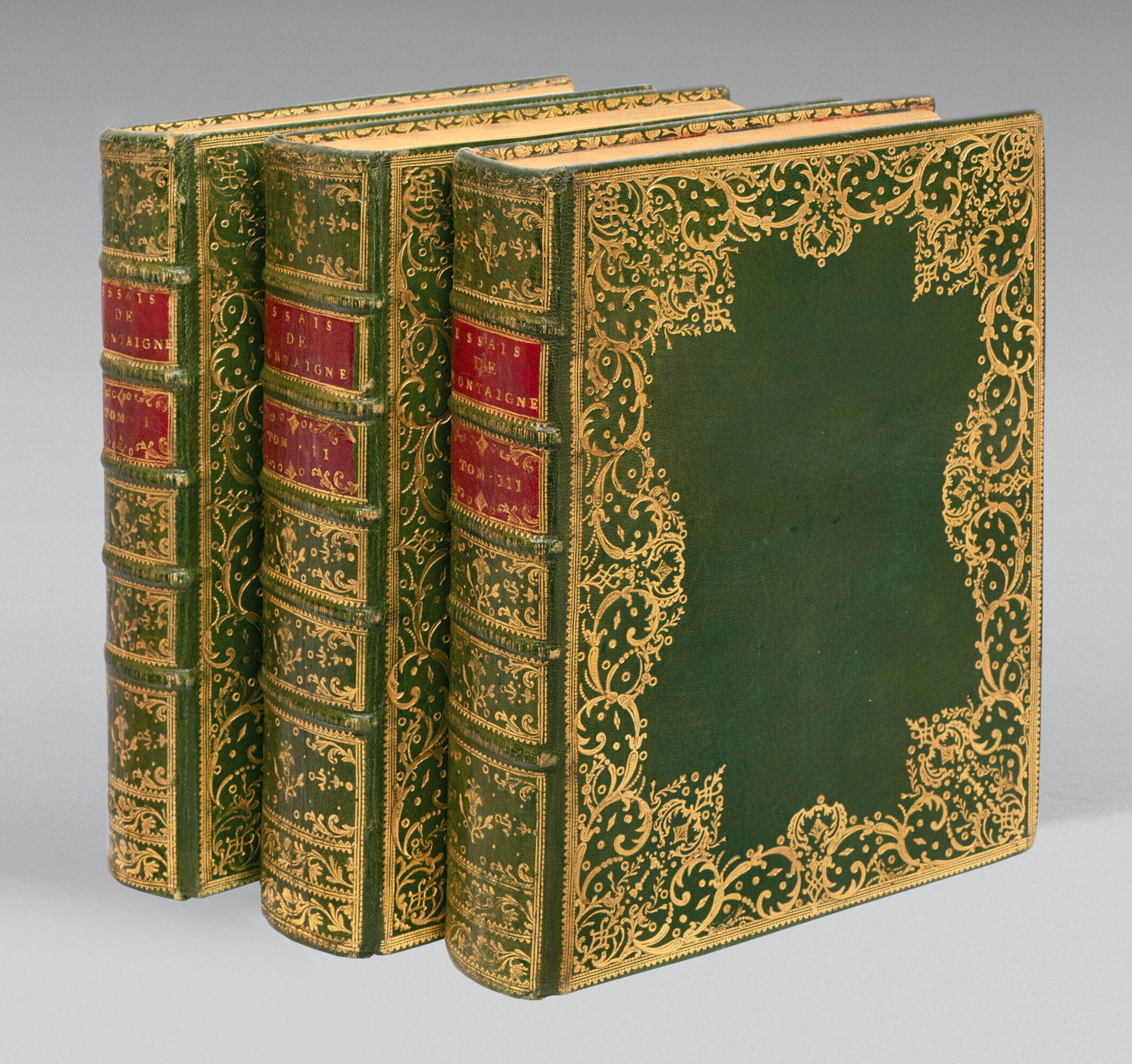

3 volumes 4to, full green morocco, covers decorated with wide gilt borders, ribbed spines decorated with gilt fleurons, red morocco lettering-pieces, gilt inner border, gilt edges. Bound in green morocco with border.

Part I: half-title; title; portrait of Montaigne, xxiv pp. and 492 pp.

Part II: iv pp., 732 pp.

Part III: half-title, title, 605 pp.

262 x 205 mm.

One of 25 copies of Montaigne’s Essays printed in 4to format on large Holland paper in 1783.

“Printed on very fine paper, and much more carefully corrected than several others by the same publisher. It contains a good table, and the old spelling has been followed…”. (Brunet, III, 1839).

“Very good edition without notes or headlines, without the translations of the quotations but specifying their authors. Bastien’s edition was a milestone in the transmission of the Essays. He returned to the sources, above Coste, to rediscover Montaigne’s text: ‘I have, as much as it was in me, made this author his own’. (Cf. P. Bonnet, ‘Un singulier éditeur de Montaigne au XVIIIe siècle’, BSAM, 5th series, n°13).

“A country gentleman from the time of Henry III, who is a scholar in a time of ignorance, a philosopher among fanatics, and who paints under his name my weaknesses and my follies, is a man who will always be loved”. Voltaire, 1734.

A breviary of humanism. Montaigne was right when he said of this book, “consubstantiel à son auteur”, that “who touches the one touches the other”. As Montaigne’s contribution was not a system, but a series of reflections that owed their unity to their close link with his “self”, admirers and detractors alike have exalted or attacked, in the Essais, not a doctrine, but a turn of mind and a quality of soul. Critical minds such as Voltaire and Sainte-Beuve, more concerned with understanding than constructing, and above all with sincerity and freedom, have loved Montaigne and hailed him as their master. Rigorous and systematic minds, those who crave the absolute, those who believe they cannot flourish without giving of themselves and surpassing themselves, such as Pascal, Malebranche (or Rousseau), irritated by his wandering allure, his penchant for egoism or the serenity with which he accepts the relative, have hated and vilified Montaigne as a seductive representative of their most dangerous temptations. But his enemies were influenced by him, and his admirers betrayed him. The debt owed to him by the classics is immense, even though they were indignant about his disorderly composition and his indiscretion in displaying his “hateful self” down to its most vulgar particularities (such as his abundant body hair, his taste for melons, or his inability to walk without pooping himself!) Quite strange, however, was the enthusiasm of the 18th century, when this conservative, this enemy of violence and passion, this prudent and moderate man, ended up becoming the patron saint of intemperate reformers, convinced atheists and even revolutionaries. These paradoxes testify to the vitality and fruitfulness of a work whose importance it would be difficult to exaggerate. The Essays, which assimilated and transmitted to us, in an accessible and even charming form, all the knowledge of Antiquity, are at the same time the first and most decisive of modern works. Without them, would we have Pascal’s lucid, vigorous analysis, Cartesian questioning, Molière’s wisdom and sense of the “natural”, La Fontaine’s mischievousness, Voltairian critical irony, Rousseau’s respect for instinct and nature, Gid’s cult of sincerity and the subtle meanderings of Proustian analysis?

When it comes to our greatest masterpieces, we mention Montaigne, because he was the first to brilliantly represent the fundamental trend in French genius that, from Pascal to Bergson, via Racine, Vauvenargues, Stendhal and Maine de Biran, produced so many psychologists and moralists. Despite his uncoordinated appearance and his disdain for logic, this Gascon gentleman was very French, with his critical spirit, his distrust of grand metaphysical constructs, his common sense and his mischievousness; with his love of life, his taste for the pleasures of the senses and those of conversation; and with his sociability as well as his good grace, his frankness and his sense of courage and loyalty.

But at the same time, he was admired by the English at a time when his compatriots despised him, and he was not without influence on Goethe. An enemy of all particularism, he made Terence’s famous line his own: “Homo sum et nil humanum a me alienum puto”, he was a humanist in the full sense of the word; The adjective human comes spontaneously to mind to characterize him, perhaps because he didn’t try to rush nature to raise it above itself, but also because he knew how to observe it finely enough to find the secret of a harmony that, while giving a good place to pleasures and the sweetness of life, doesn’t exclude the joys and efforts that make up the dignity of a human life.

Precious and superb copy bound in contemporary green morocco with wide gilt borders from the libraries of the Princesse de Faucigny-Lucinge, then Rothschild.

Among the 25 copies printed on large Holland paper in 1783, this is the only one recorded bound in contemporary green morocco with wide and beautiful gilt border.