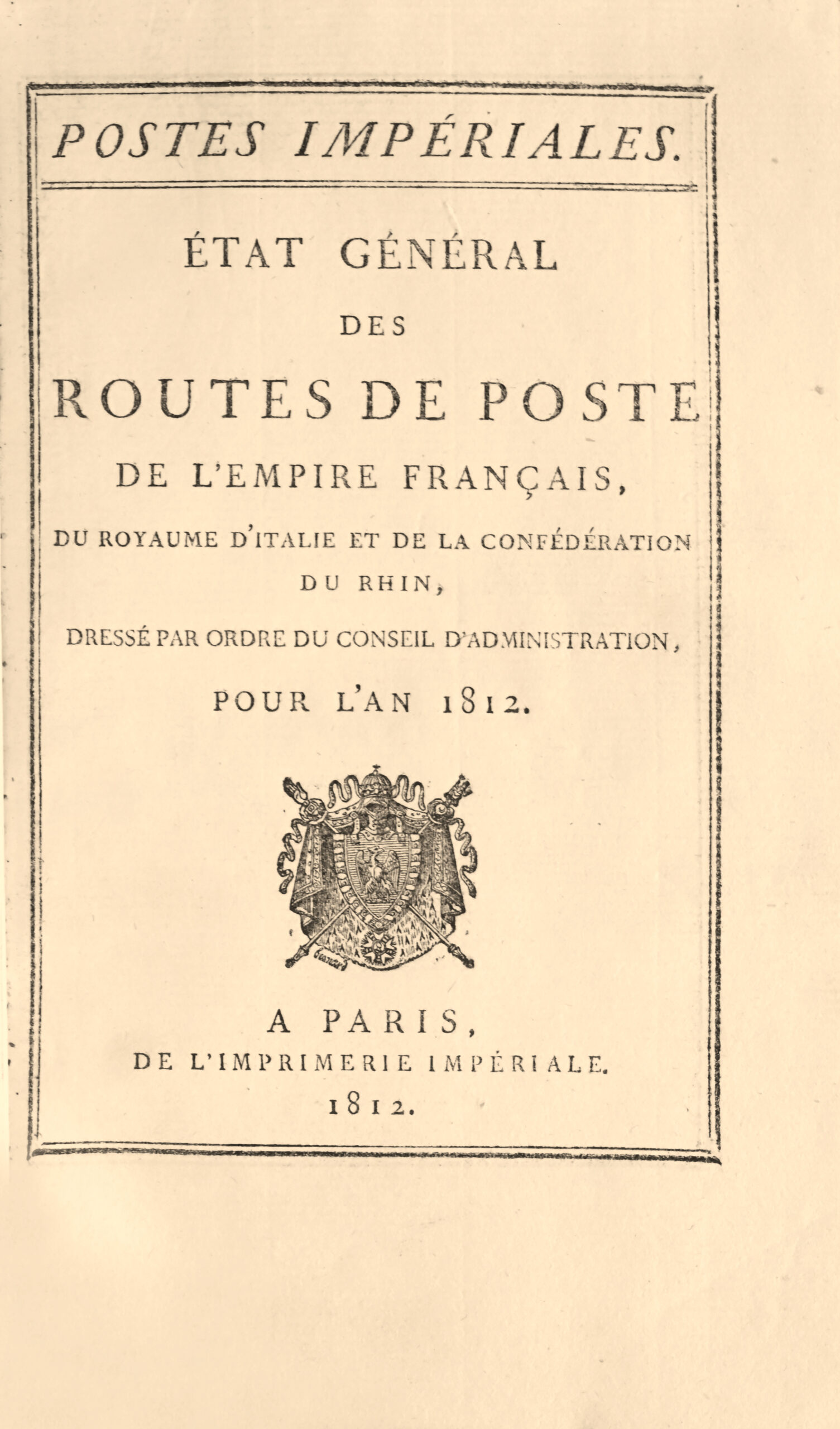

Paris, Imprimerie Impériale, 1812.

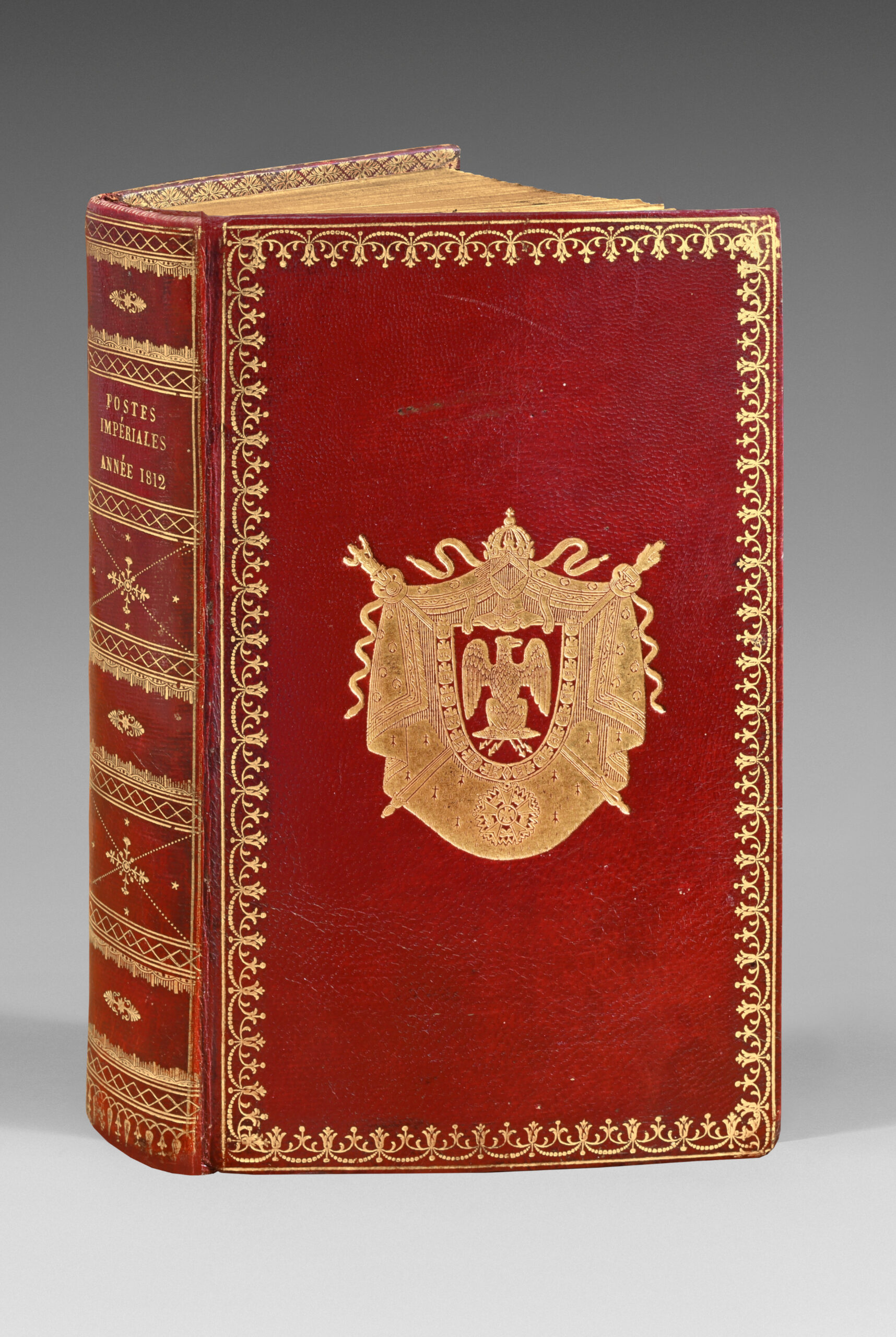

Large 8vo with 362 pp. Straight-grained red morocco, wide gilt frame around the covers, arms in the center, decorated flat spine, gilt inner border, blue moire endleaves, gilt edges. Contemporary binding.

205 x 120 mm.

A sumptuous copy of the general state of the Posts of the French Empire for the year 1812.

Printed on imperial Holland paper, this state of Imperial Posts opens with the calendar for the year 1812.

It is preserved in its brilliant red contemporary morocco binding with the arms of Emperor Napoleon I.

I) The empire post was ‘invented’ by the great clerk Gaudin. Gaudin had worked in the finance offices since 1775 under Calonne and Necker. Appointed Postmaster General by the Directoire, he became Minister of Finance on 18 Brumaire and remained so throughout the Empire. It was he who definitively broke with the Farm system and ensured that the Ministry of Finance took control of the postal service.

The exclusive monopoly on the transport of letters was once again proclaimed by the decree of 27 Prairial an IX, a text considered to be the basis of contemporary regulations. Article I states: ‘It is forbidden for all independent carriage contractors and any person outside the postal service to interfere in the carriage of letters, newspapers, handwritten sheets and periodicals, packets and papers weighing 1 kg or less, the carriage of which is entrusted exclusively to the letter post administration’. In 1802, maritime and colonial correspondence was reorganized along the same lines.

II) Postmasters. The efficiency of letter post relied entirely on the postmasters, of whom there were 1,400 throughout the country, who maintained around 16,000 horses and paid 4,000 postilions.

III) An instrument at the service of the empire. The reason why the Empire took such pains to re-establish the postal service was that it saw it as an instrument of government. The Emperor was very sensitive to the accuracy of mail.

IV) Army Post. The almost permanent state of war in the Empire made it necessary to organize the armed forces postal service, for which general regulations were published in 1809. The authority of the Director General of Army Mail, who was attached to the Directorate General of the Post Office, began at the frontier office where letters destined for armies in the field were exchanged.

V) Little progress in speed. Although the imperial postal service underwent decisive administrative reorganization, its technical resources and therefore the average delivery time for letters and travelers did not improve significantly compared with the Old Régime. In the Napoleonic era, an express courier could cover the distance from Paris to Châlons-sur-Marne in a dozen hours, a Messageries mail coach in sixteen and a diligence in twenty. These figures should be compared with the time taken by couriers on the main Champagne routes in 1737, which we know precisely. Coming from Paris, they needed at least 23 hours and 30 minutes to reach Reims or Troyes, and 25 hours for Châlons, which corresponds to an average of about 7 km per hour. These averages seem to have been only slightly improved until the end of the Empire; they were the best possible for a single, loaded letter; they depended largely on the state of the roads, which were more or less well maintained.

In addition to listing the roads of the Empire and their relay stations, the Etat des postes also indicates the distance between them of all the roads either leading from Paris to all the main towns, or connecting these different towns together. This State is preceded by a calendar for the year 1812, an extract from the laws and regulations on horse mail, rates, etc…

The constant territorial expansion of the French Empire was bound to make it increasingly difficult for Napoleon to transmit any written message from one end of Europe to the other as quickly and easily as possible.

When the Empire was proclaimed on 18 May 1804, the Post Office was headed by Antoine Marie Chamant de Lavalette, Director General of the Post Office. Devoted to the Emperor, Lavalette remained in this position until 1814.

The smooth running of the Post Office was essential to the Emperor. Political and even diplomatic problems were therefore bound to have an impact on the operation of the Post Office. Territorial conquests forced postal administrators to adapt the organization of postal services. The new territories were divided into departments. The postal administration was integrated into these new administrative structures. The same operating rules were applied throughout the Empire.

A second major service was placed under the authority of the Director General of the Post Office: the Relais service, i.e. the administration of the horse post office.

The Relais de Poste were first and foremost used by couriers working for the administration of the Poste aux Lettres, where they could find the fresh mounts that the postmaster was obliged to reserve for them. Although they did not use the postmasters’ horses, public carriage contractors were obliged to pay them 25 centimes per horse per post for each of their carriages.

In addition, the development of the estafette service favoured postmasters who made their postilions available to the administration to ensure the transmission of urgent government mail.

All the regulations concerning the horse post service, the rates, the name of the different relay were indicated in post books, officially called ‘Etat général des routes de poste’. These directories, which enabled travelers to establish their itinerary and the price to be paid for their journey, were updated and published every year.

A sumptuous copy of the general state of the Posts of the French Empire for 1812.

It is preserved in its brilliant contemporary red morocco binding with the arms of emperor Napoleon I. (Olivier, Pl. 2652).