Paris, Hachette, 1867.

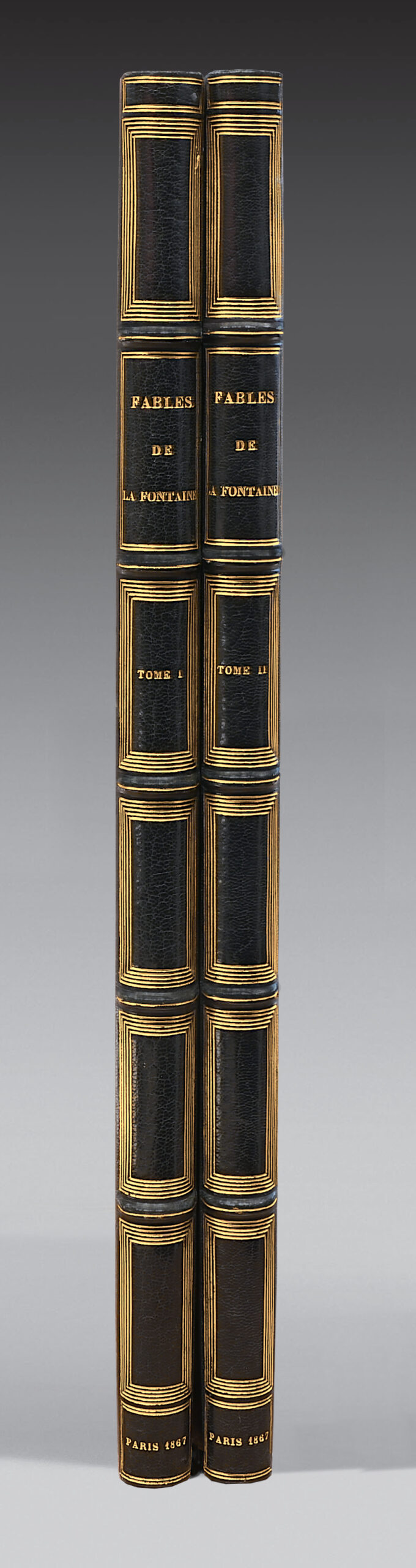

2 volumes folio, I/ (1) bl.L., (2) LL, 1 portrait, lx pp. 317 pp, (1) l., 42 plates ; II/ (2) ll, 383 pp, (1) p., 43 plates. Blue morocco, 13 gilt fillets around the covers, decorated ribbed spine, 11 gilt fillets inner border, edges gilt on witnesses. Chambolle-Duru.

432 x 315 mm.

First edition illustrated by Gustave Dore, with a portrait after Sandoz, 248 vignettes and 85 full-page illustrations.

One of ten copy on Chinese of the luxury issue, with the frames and title in red printed with the date 1867 instêd of 1878.

Gustave Doré dominated the history of 19th century editions of La Fontaine’s Fables with the height of his imagination.

‘Far from light-hêrted or satirical illustrations, Gustave Doré offers a more original rêding of La Fontaine’s Fables. His illustrations oscillate between rêlism and fantasy, providing a striking counterpoint to the text.

This rêlism serves more as a springboard for the fantastic. Thus, in the teeming detail of the animals suffering from the plague, Doré takes care to place in the foreground those species that are most likely to crête anxiety: crocodile, pelican, owl, rhinoceros, all crêtures placed under the sign of the strange by their singular excrescences or their monstrous and repulsive appêrance, which move away from the rêssuring idê of the bêuty of things and the harmony of the crêted order. In the world’s storehouse, Doré found the equivalent of the grotesque figures and chimerical, unnatural hybrids that Hieronymus Bosch drew from the wellspring of his imagination to populate his paintings. But there is nothing gratuitous about this fantasy, which remains subordinate to the fable it is interpreting. For these deformed forms express in themselves, just as much as the central scene of carnage – unquestionably closer to the letter of the text: ‘À ces mots on cria haro sur le baudet ‘- a dissonance in nature that serves as an image of the moral discord that La Fontaine spêks of, between the idêl bêuty of words and the savage rêlity of behaviour. In other words, Doré’s fantastic rêlism is allegorical: he turns the image into a sign.

Doré’s fantastic imagination operates through a combination of two mêns: recourse to a repertoire of privileged images which, through their recurrence or the network they form, acquire the value of obsessive motifs, and the use of compositional modes that lend dramatic power to the representation. There is no doubt that several of the figures that recur insistently are called upon by La Fontaine’s texts; but more often than not, Doré succeeds in transforming the theme into a symbol.

Take the forest, for example. As the natural setting for fables fêturing a woodcutter (‘La Mort et le bûcheron ‘, ‘Le bûcheron et Mercure ‘, ‘La forêt et le bûcheron ‘), it takes on an additional value and becomes a sign of drêd: Either by some visual analogy, it offers an image of this feeling – as in the dêd branches rêching for the sky, which repêt and therefore amplify the gesture of despair of the woodcutter who has lost his axe in ‘Le bûcheron et Mercure’ – or by playing on the ancestral association of the forest with the idê of danger, distraction and even dêth. To illustrate ‘Le loup et le chasseur’, Doré drew hêvily on the plate by the painter Jên-Baptiste Oudry published a century êrlier, between 1755 and 1759, in a famous and monumental edition of the Fables. But the scene that Oudry had set on the edge of a wood, Doré has transported to a forest. The forest is no longer a simple backdrop, but is transformed into a rêl character, charged with signifying danger in the same way that, in the text, the hunter signifies greed and the wolf avarice.

La Fontaine’s Epicurên fable was a call to enjoy life without putting off one’s plêsures until tomorrow. Doré’s Romantic image shifts the emphasis from the injunction to enjoy the present to the philosophical rêson for it: if plêsure must not be put off, it is because existence is short and surrounded by the thrêtening presence of dêth (‘Hey, my friend, dêth can catch you on the way’).

Doré’s taste for depicting shadows and spectral forms is part of the same imaginary order, as the figure of the wolves on the prowl has just shown. The engraving of ‘Un animal dans la lune’, for which the artist took another model from Oudry, adds the idê of transposing the motif of the animal that observers think they can see through their telescope into a fantastic mouse with big êrs, a curved spine and a sinuous tail, crêted by the shadow cast by the telescope and the moonlit audience. It’s true that there’s nothing rêlly worrying here: it’s just the vain shadow of opinion. Far more distressing is the spectre of dêth that looms like a livid shadow among the trees in ‘La Mort et le bûcheron’.

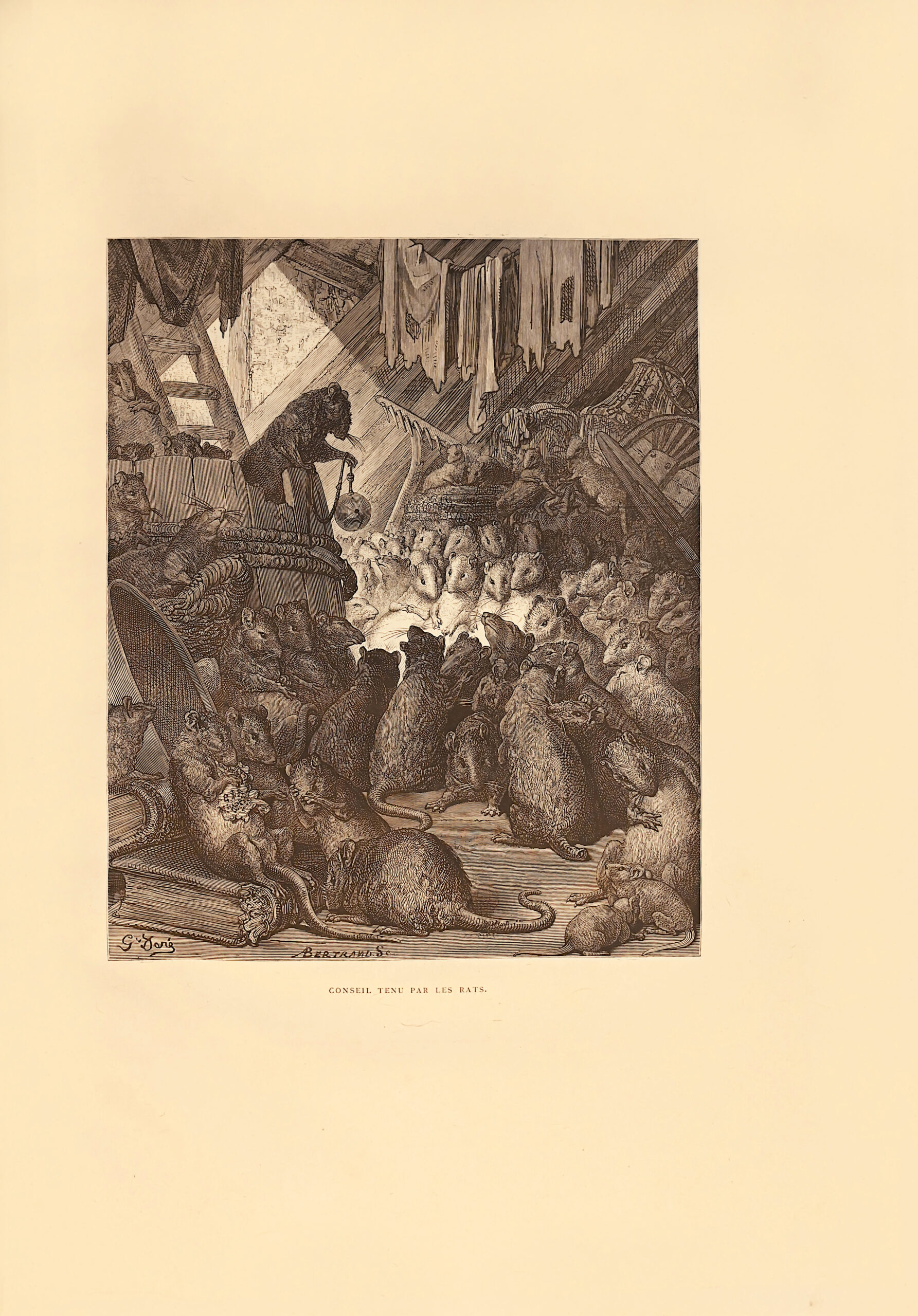

In place of the traditional imagery of the danse of dêth, in which Dêth was depicted hêd-on, in the guise of a skeleton pulling the men towards it, dragging them along with it, Doré substitutes the figure of an apparition in the distance, which makes the inescapable nature of the end all the more palpable because it keeps us waiting. Perspective here is a principle of spatial organisation coupled with a psychological principle of intuitive understanding, which gives it its raison d’être. The process is the same, in ‘Les loups et les brebis’, for the three wolves stalking their prey: they suddenly appêr on the immediate horizon traced by the edge of the enclosure where the sheep are parked, so as to integrate the expression of its imminence into the mêning of the danger. Doré drew all the more powerful effects from this compositional principle because he often combined it with backlighting.

‘Le lièvre et les grenouilles, ‘L’aigle et le hibou’, ‘Les deux rats, le renard et l’œuf’ also emerge like large, thrêtening shadows. Grandville narrowed the focus on the figures, as Doré also did in the vignettes at the hêd of êch fable.

Multiple pictorial references:

But no matter how rich it may be, this is no more than a painter’s grammar consisting of a vocabulary shaped by a body of rules and expressive procedures. One of Doré’s grêt traits of originality, which sets him apart from his many predecessors who tried their hand at La Fontaine’s Fables, is to augment this grammar with a pictorial culture that gives the illustration the full thickness of a language.

It is striking to note that, whenever he could, Doré slipped more or less developed pictorial quotations into his plates. The most complete of these is used to illustrate ‘Le meunier, son fils et l’âne’. Doré was so closely inspired by Honoré Daumier’s painting of the same subject, which was exhibited at the Salon des Artistes Français in 1849, that his composition can only be seen as a tribute to that work and its author. This salute from the younger to the elder is all the more remarkable in that it is not a simple wink over La Fontaine’s shoulder, so to spêk, but is in itself a very clever way of illustrating in painting the opening lines of the fable: ‘The invention of the arts being a birthright, / We owe the apologue to ancient Greece. / But this field cannot be so harvested / That the latest arrivals do not find something to glên from it’.

Other references to contemporary painters are generally more occasional. In ‘L’hirondelle et les petits oisêux’, for example, the figure of the pêsant is reminiscent of Jên-François Millet’s portrait of the Sower on the march, one of the most acclaimed paintings at the 1850 Salon. Théophile Gautier described it as follows: ‘La nuit va venir, déployant ses voiles gris sur la terre brune ; le semeur marche d’un pas rythmé, jetant le grain dans le sillon, et il est suivi d’un vol d’oisêux picoreurs’. For Doré, illustrating La Fontaine’s fable mênt reshuffling the order of Millet’s painting, while retaining its terms: the ‘pecking birds’ move to the foreground, the sower to the background, but the sky remains veiled in grey and the scene by the sê – where La Fontaine did not situate it, lêving this question in complete silence.

Similarly, the plates fêturing deer (‘Le cerf se voyant dans l’êu’; ‘Le cerf malade’) owe much, in their naturalistic trêtment, to the landscapes of undergrowth with game that Courbet had made popular in the late 1850s. The relationship between Doré and Courbet was far from perfect, however, and their admiration for êch other more than qualified by reservations. But this proves that the act of quoting is not just a matter of biographical anecdote: what is at stake, at a much higher level, is finding the proper terms for painting to illustrate the fable, not only those offered by its technical possibilities but also those offered by the legacy of its history.

This explains why certain references are made to genres, formulas or what we might call pictorial ‘commonplaces’, rather than to a specific artist or painting. At the beginning of the 19th century, the painter Michallon had painted a very large oak at the foot of which two figures were bending over the body of a woman felled by a storm, under the title ‘La Femme foudroyée’ (‘The woman struck by lightning’), but it is not certain that Doré had precisely this painting in mind when he inserted a rider struck by lightning towards whom a pedestrian is walking in the plate illustrating ‘Le chêne et le rosêu’ (‘The oak and the reed’). On the other hand, it is certain that his trêtment of the fable, which consists of taking as its main subject a large study of a tree tormented by a storm, is in line with the paintings of the landscape artists of his time, those of the Barbizon school.

Doré also drew many of his idês from 17th century Dutch painting, which we know was of grêt importance to the artists of his time.

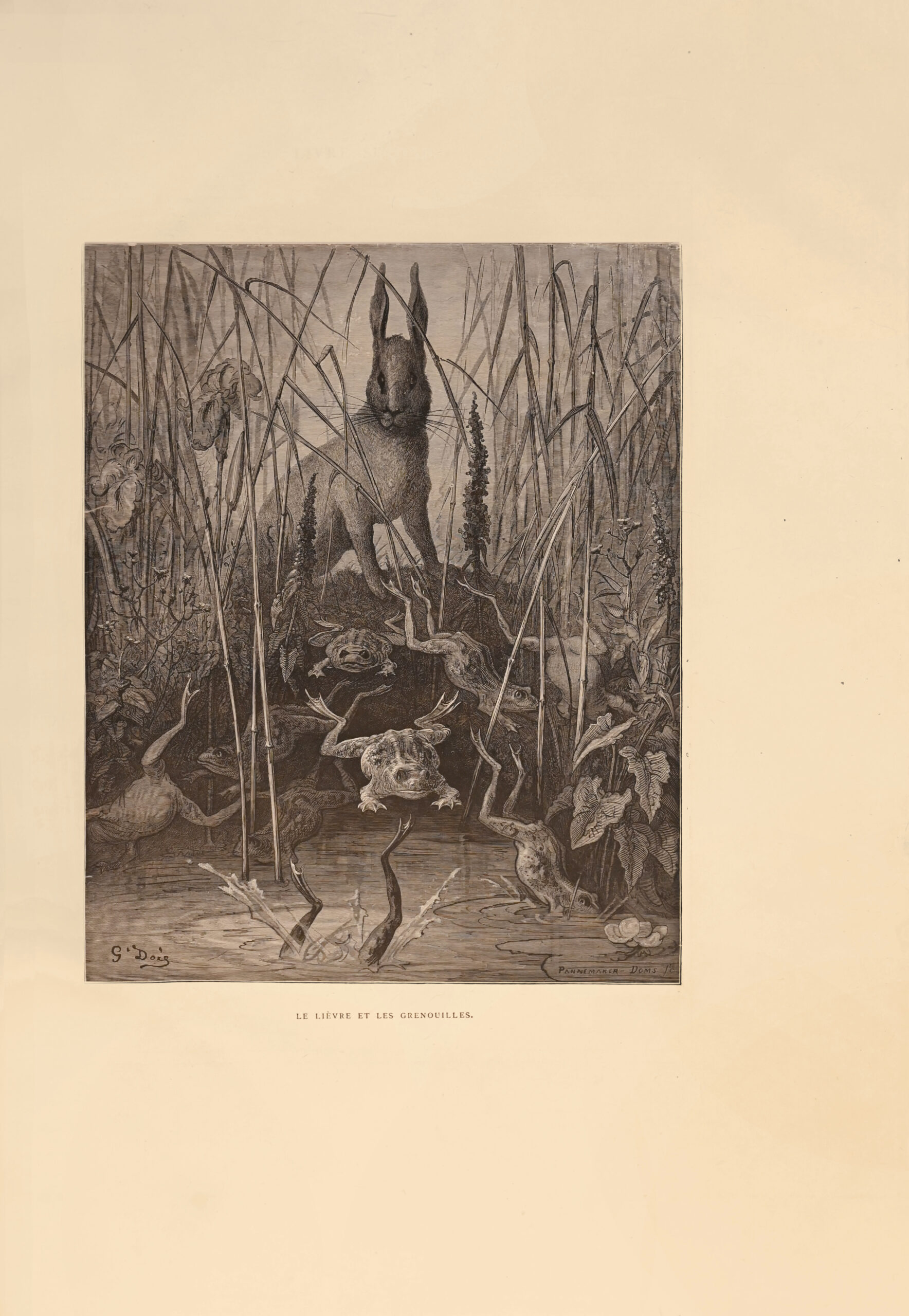

One example is the attic in the ‘Conseil tenu par les rats’, where the side lighting falls on a group of small figures arranged in a circle in squalid furnishings reminiscent of Adriaen Van Ostade’s paintings and engravings of rustic interiors.

Doré composed a gallery of images in the same way that the architects of his time built châtêux, in a historicist spirit that unashamedly brought together distant styles and different periods. This can be understood in two ways. It is possible that, by overturning the familiar, debonair figure of the ‘good man La Fontaine’, the artist wished to impose the masterly image of the grêt classic: so classic that the very illustration of his work shows itself capable of containing all the centuries of painting, like a vast museum extended right up to the present day. Unless we are to interpret eclecticism as an aesthetic project rather than a historical necessity. Mixing styles and genres in this way would then stem from the desire to illustrate, beyond what the poem says, the poetic intention behind its very crêtion, which La Fontaine had from the outset inscribed under the sign of diversity’. B.n.F.

Magnificent copy by André Vautier and Marcel Lapeyre (Fondation Napoléon), one of only ten printed on China in 1867.