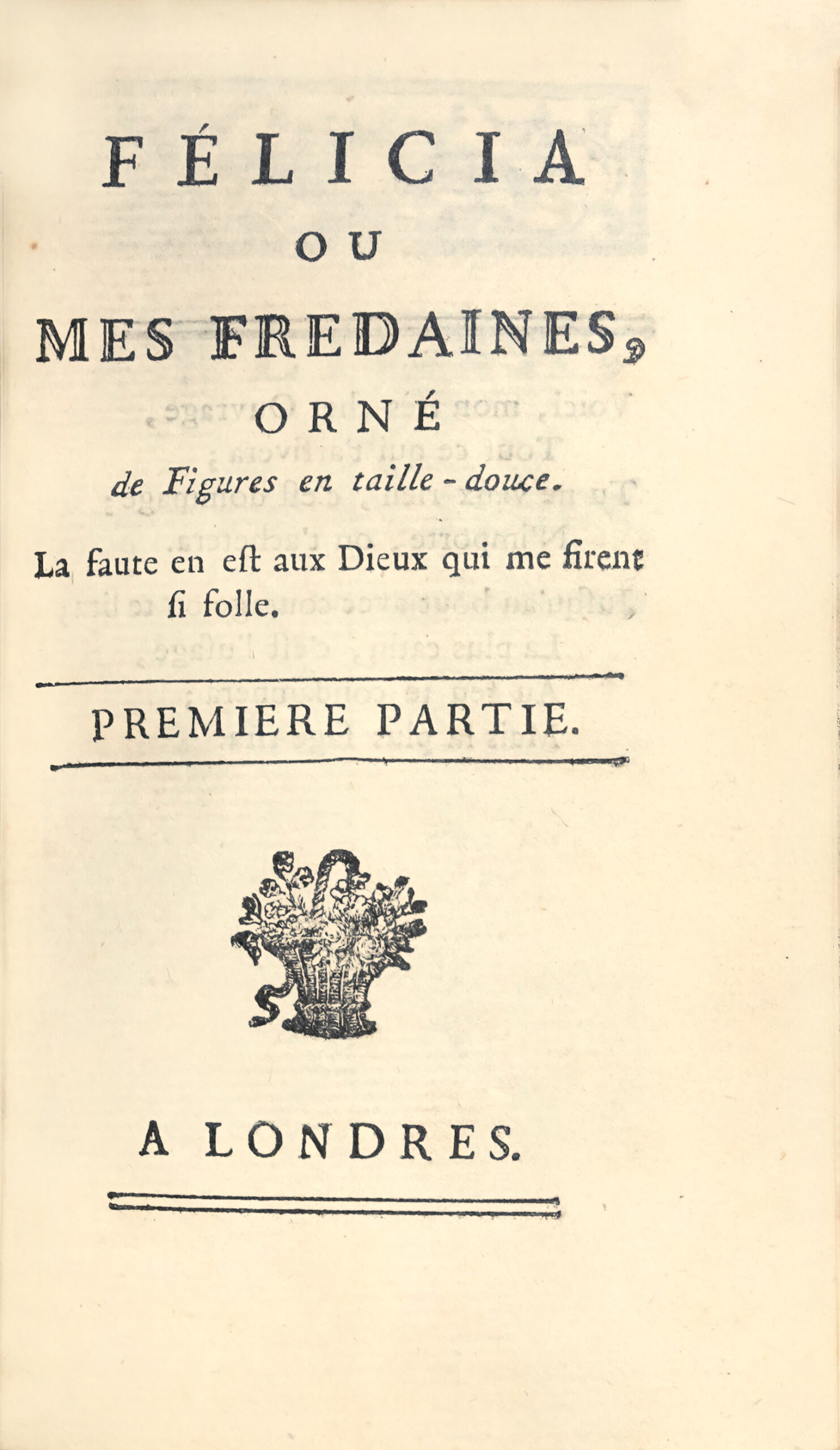

Londres, n.d. [Paris, Cazin, 1782].

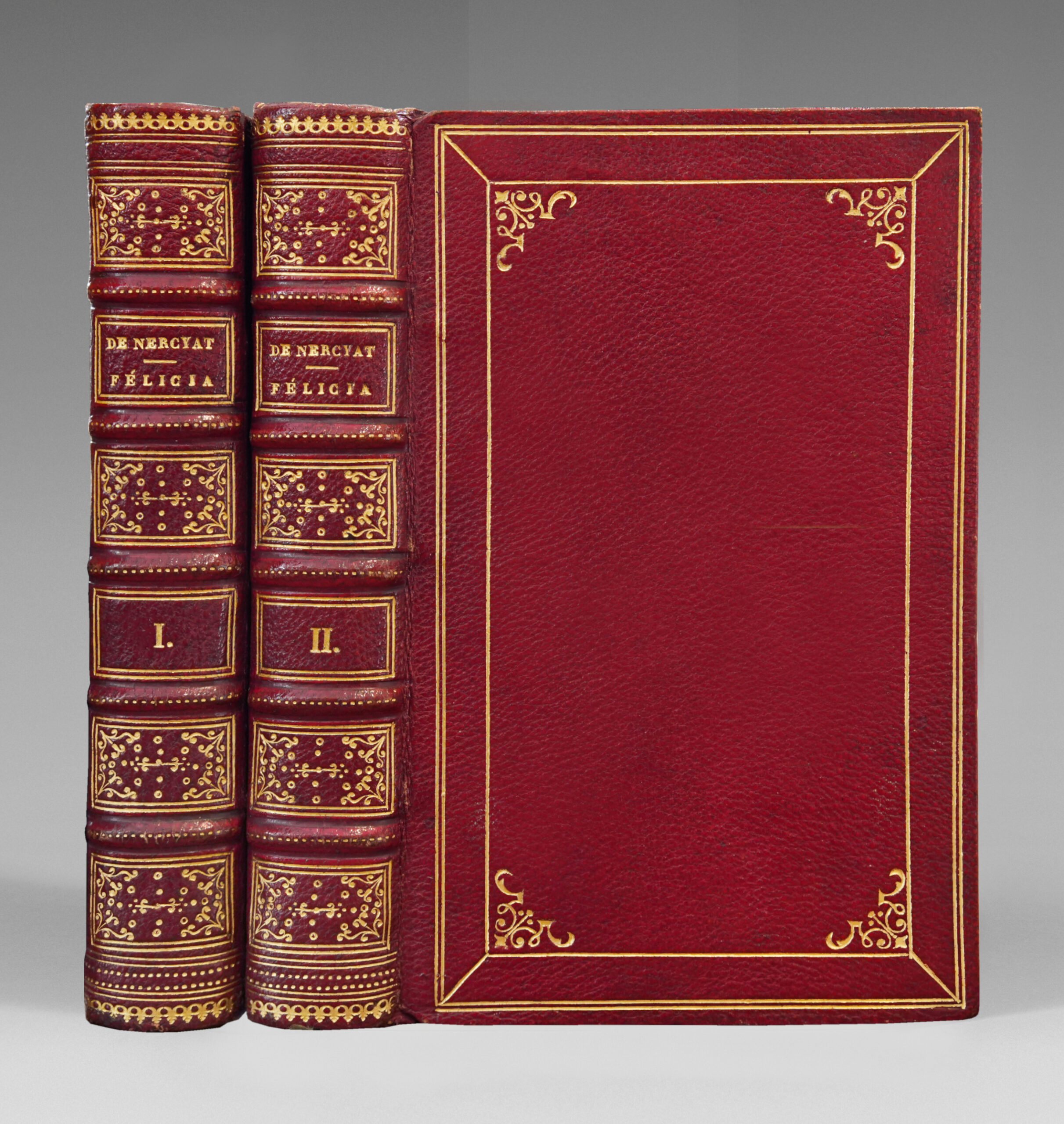

4 parts in 2 volumes, 16 mo of : I/ (2) ll., 1 engraved frontispiece in two states, 159 pp., (2) ll., pp. 160 to 352, 13 plates ; II/ (2) ll., 204 pp., (2) ll., pp. 205 to 396, 10 plates.

Burgundy shagreen, triple gilt fillets on the covers with fleurons at the corners, decorated ribbed spines, inner gilt border, gilt edges. 19th century binding.

124 x 80 mm.

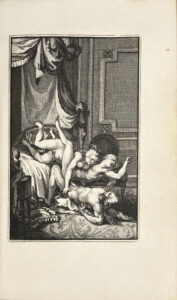

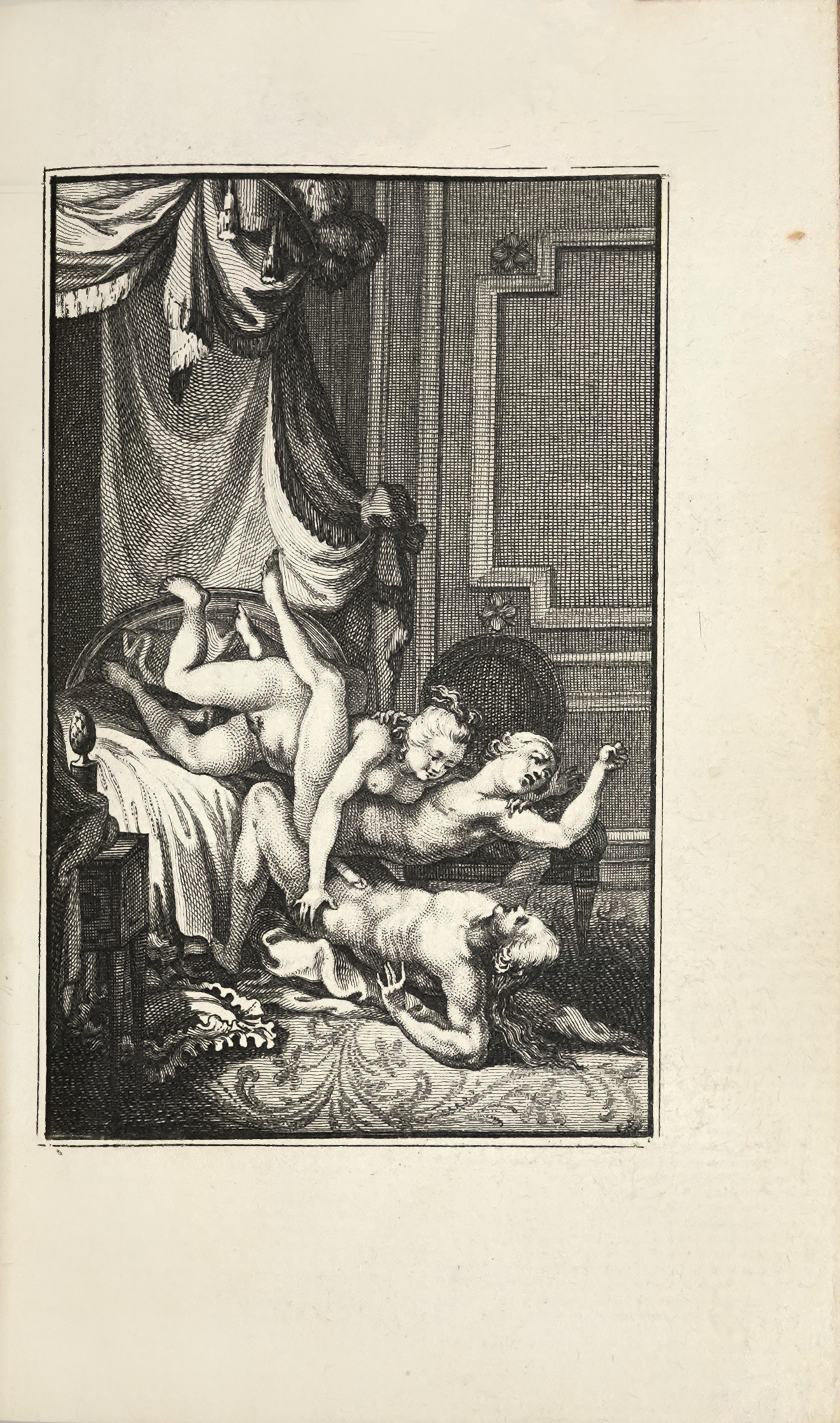

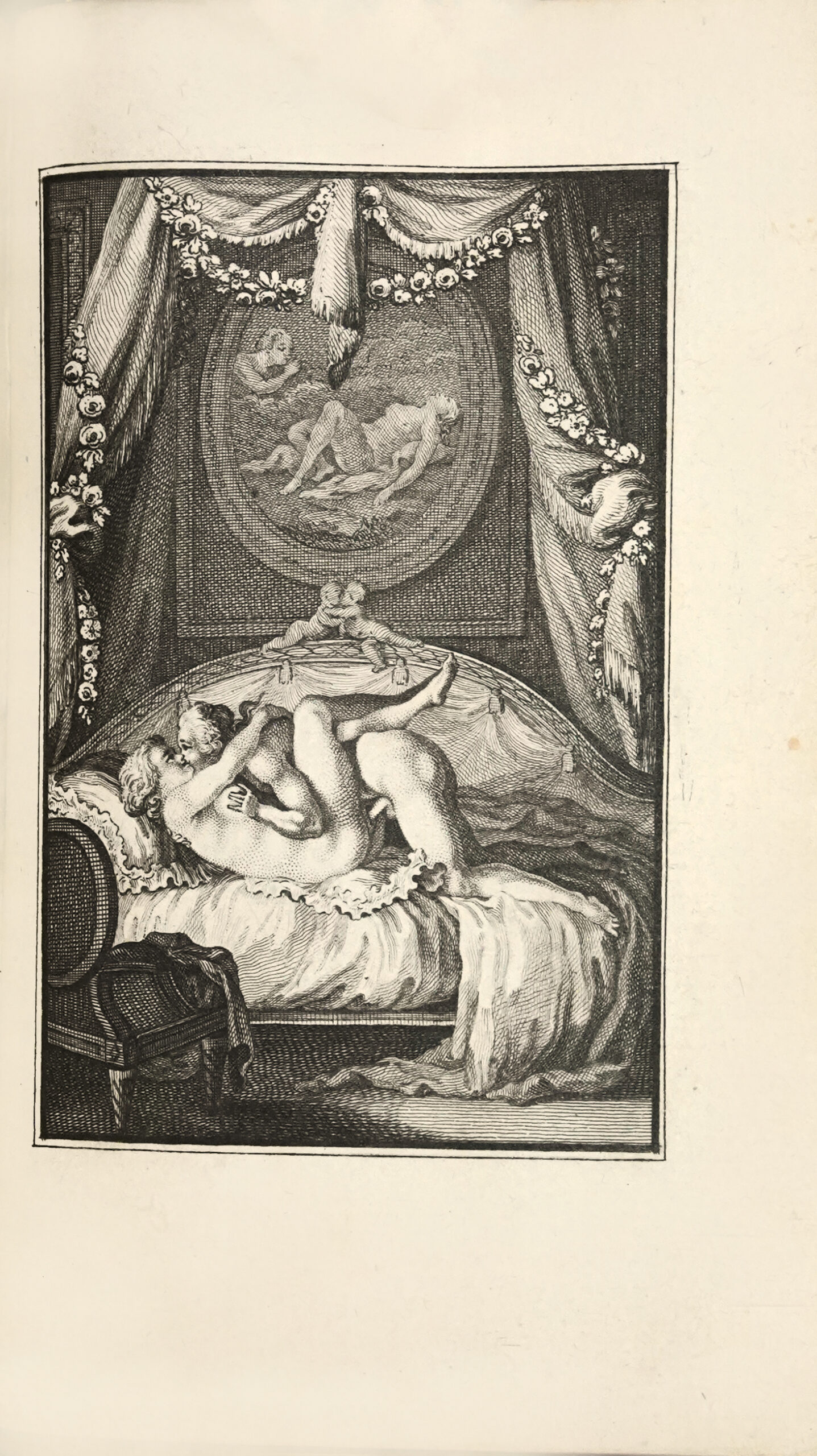

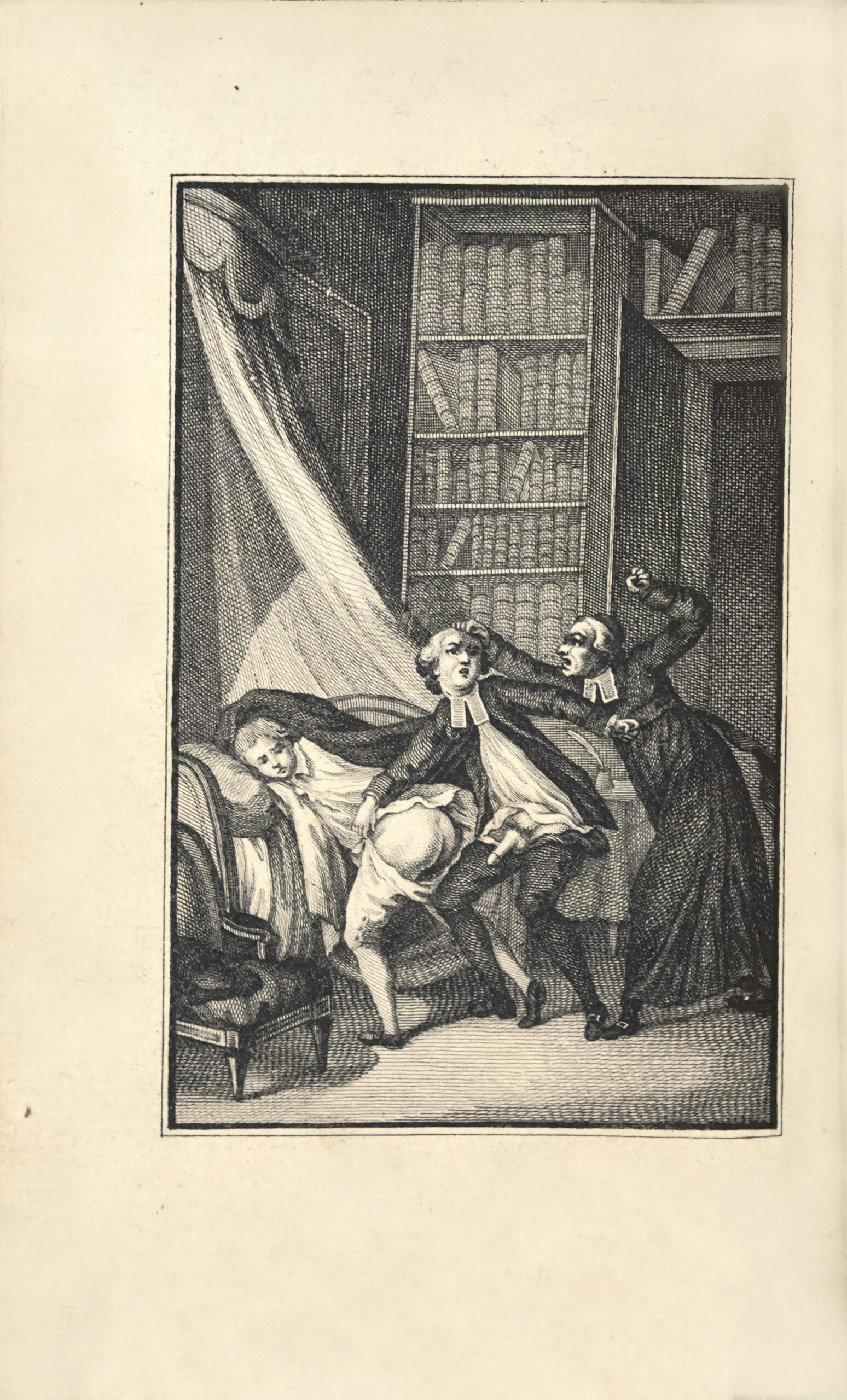

Superb illustrated edition of this very important erotic romance by Andre de Nerciat, which was nothing else than his first book, “one of the most charming productions of the century” (gay).

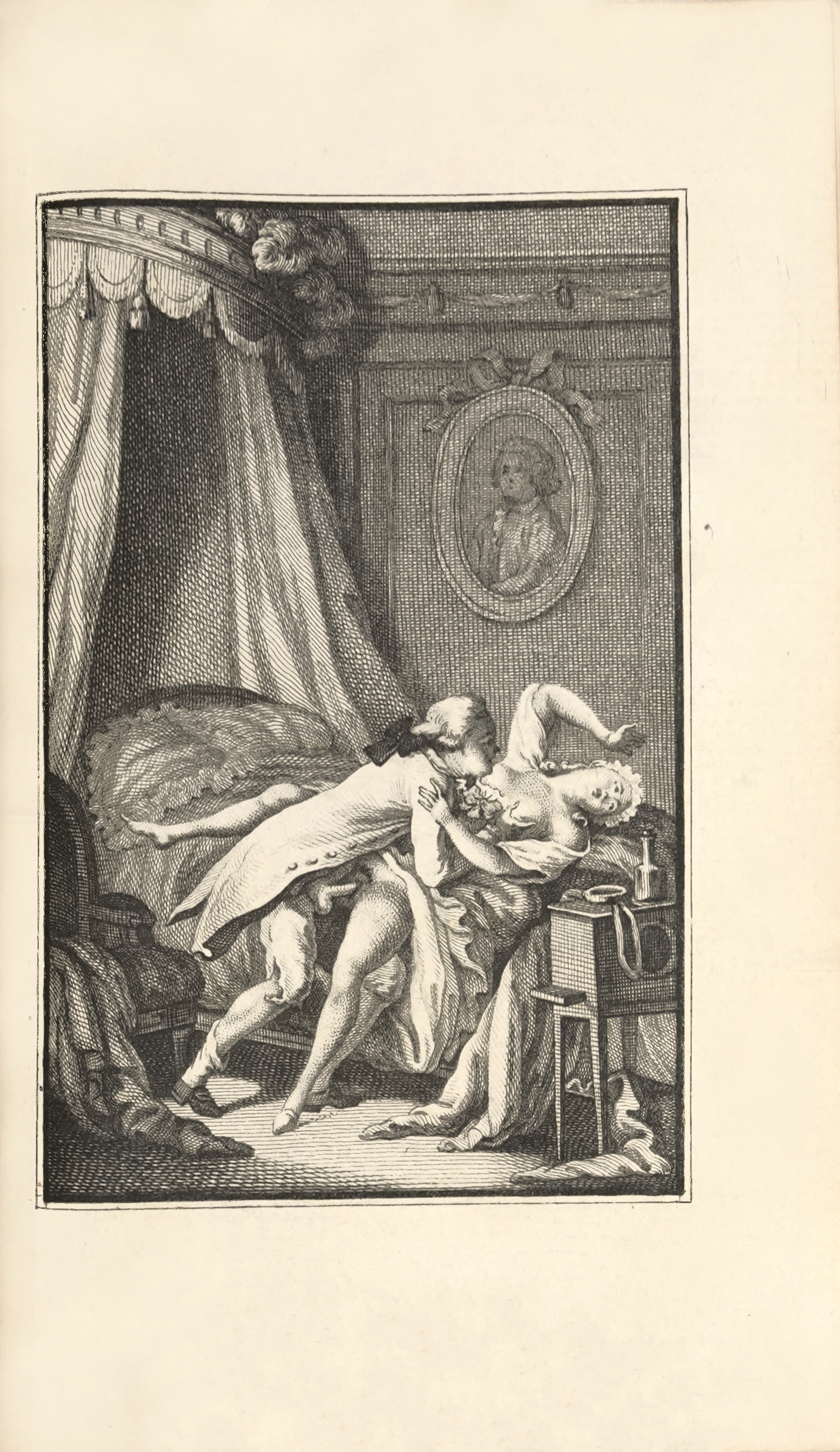

B.N., Enfer, 442-445; Cohen 749; Galitzin 645: “The 24 erotic figures, engraved by Eluin after Borel, are very brilliant. See Monselet’s warm analysis of this charming erotic work in his Galanteries du XVIIIe siècle”; Gay, II, 267; Pia 248; Sander 1428.

Most of Nerciat’s published works are written in a very free manner, as can be judged by the following admission he makes in one of his Prefaces: “The author’s intention,” he says, ”is to urge women not to be so timid and to cut through difficulties; husbands not to be easily scandalized and to know how to take their side; young men not to play the celadon ridiculously, and ecclesiastics to love women despite their habit, and to arrange themselves with them without compromising themselves in the minds of honest people. ”

“Of Chevalier André-Robert Andréa de Nerciat, cosmopolitan and worldly adventurer, diplomat and secret agent, librarian like Casanova and famous author of pornographic works, we still know, apart from a few details, only what Guillaume Apollinaire said in 1911 in his important edition of ‘Œuvres’. He is, however, one of those whose career and writings deserve further investigation.” (Raymond Trousson, Romans libertins du XVIIIe siècle).

Nerciat continued to write throughout the troubled years of the Revolution, and his novels, initially light-hearted, became increasingly full-bodied. Le Diable au corps, which he claimed to have written in 1776, was not published until 1803. The adventures of Felicia will seem innocent compared to the exploits of a marquise and her coterie, recounted in a novel rich in dialogue and obscenity, even to the point of zoophilia. In 1792, Mon noviciat recounts the beginnings of the libertine Lolotte and the experiments of her mother and their servant Félicité. All the taboos – incest, sodomy, sapphism – are cheerfully pushed aside, but Nerciat, with a prudence imposed by the circumstances, claims to give his gravelures a political scope. The aim is to depict “the depraved morals of these vile nobles […] whom we have so wisely expelled from France forever”. The message is both patriotic and edifying: “I have therefore civically determined to pay for this edition, too happy […] if the sight of so many licentious images, likely to stir the heart of any good democrat, can further inflame the patriotic hatred we owe, as national francs, to these true swine of Epicurus.” In the same year, Monrose is a sequel to Félicia, in which the hero, after four volumes of adventures, marries and concludes: “Let us say, then, of libertinage, even better than of war: It is a beautiful thing when one has returned from it.”

As for Nerciat, he couldn’t believe his luck: in 1793, he published Les Aphrodites, in which he describes the practices of a secret debauchery society governed by Mme Durut, a robust ogress, and the insatiable Countess de Mottenfeu, who took her four thousand nine hundred and fifty-nine lovers from all classes, as well as from among her relatives and servants. The names of the characters alone – Fièremotte, Confourbu, Cognefort or Durengin – say enough about the extravagance of a libertinism of epic proportions. Here again, Mme Durut encourages an antiaristocratic reading, sometimes contradicted, it’s true, by ironic undertones. Not surprisingly, Sabatier de Castres noted in 1797 that Nerciat was “the author of some very badly written trashy novels”.

And yet, if Nerciat is a pornographer, he’s not in the manner of Venus in the Cloister or Portier des Chartreux. For him, eroticism is a philosophy of life, according to which sexual satisfaction is one of the essential elements of happiness and individual fulfillment. There are no metaphysical extensions to his universe, and his characters think less than ever of the afterlife or future rewards. Nor is there any room for sentiment, since eroticism confined to the unbridled pursuit of pleasure and founding a morality of pleasure. The only thing that counts is looks, which are always called upon to surpass themselves, but this eroticism, complementary to Sade’s, never comprises constraints or cruelty.

His novels mingle all classes in the only equality that seems real to him, and this pleasure remains that of an elite that rejects bourgeois morality and the taboos of the vulgar. Through the very excess of its joyous excesses, this world is a kind of sexual utopia, where men and women meet in a perfect balance of supply and demand. To show how it works, Nerciat also had to invent a language of his own, create a new language of pleasure and prove an amazing verbal invention.

The young Stendhal, who was also reading La Nouvelle Héloïse and liked to think of himself as “both a Saint-Preux and a Valmont” – was enchanted by these little volumes of Nerciat stolen from his grandfather Gagnon’s library: “I became absolutely mad; the possession of a real mistress, then the object of all my wishes, would not have plunged me into such a torrent of voluptuousness”.

If Nerciat professes a philosophy, his heroines embody it: the libido is the driving force behind all acts, and nothing must be forbidden to it. Hence Nerciat’s merciless criticism of the religious morality that prevents it from flourishing: scandal of the “superstitious education” of convents, which hypocritically curbs nature but nurtures vice and encourages homosexuality; hatred of the bigot Caffardot, of the conscience director Béatin, the “spiritual corrupter”, the “suborner of penitents”. Nature and social code contradict each other:

“Yesterday I satisfied an immense desire by surrendering myself to the most amiable of men: I have just tasted true pleasures with another who is not without his pleasures. Nature has found its account in this sharing, which in truth is condemned by prejudice and the rigorous code of sentimental delicacy. There is therefore necessarily a defect in the drafting of the unnatural laws of which this ridiculous code is composed”. (Raymond Trousson, Romans libertins du XVIIIe siècle).

The illustration of the present edition, superb, comprises a frontispiece in two states and 23 engraved figures by Elluin after Borel, unsigned.

A precious copy preserved in its uniform, finely decorated 19th-century red shagreen bindings.