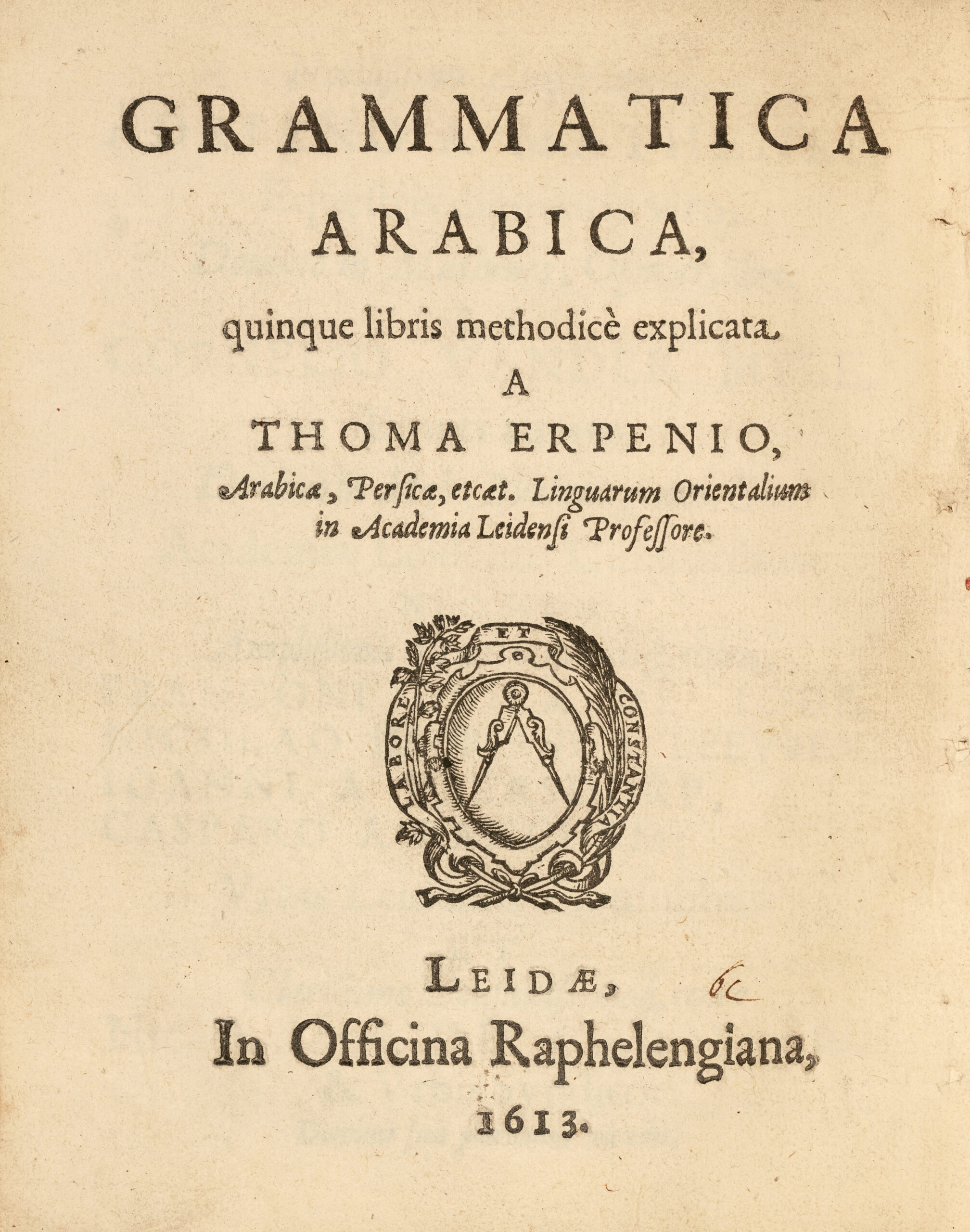

Erpenio, Arabica, Persicae, etc.

Leyde, in officina Raphelengiana, 1613.

– [With]: II/ Rous, Francis. Archaeologiae Atticae libri tres. Three bookes of the Attick Antiquities. Containing The description of the Citties glory, government, division of the People, and Townes within the Athenian Territories, their Religion, Superstition, Sacrifices,…

Oxford, Printed by Leonard Lichfield for Edward Forrest, 1637.

– [With]: III/ Crinesius, Christoph. Babel Sive Discursus de confusion linguarum, tum orientalium: Hebraicae, Chaldicae, Syriacae, Scripturae Samariticae, Arabicae, Persiae, Aethiopicae : tum Occidentalium, nempe, Graecae, Latinae, Italicae, Gallicae, Hispanicae,…

Nuremberg, Simon Halbmayer, 1629.

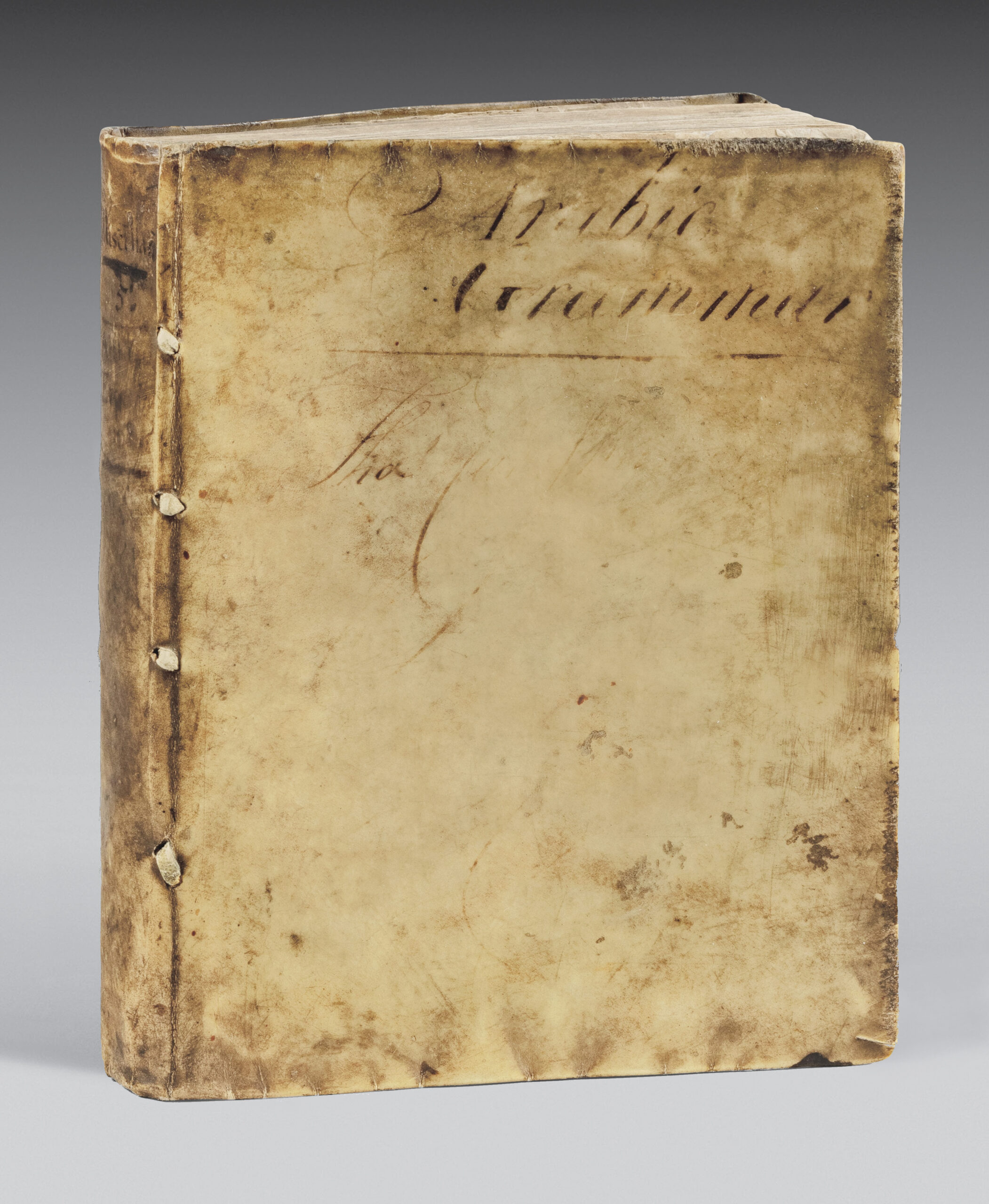

Thus 3 volumes bound in one 4to volume [186 x 147 mm] of : I/ (4) ll., 192 pp., (2) ll. of errata ; II/ (4) ll., 149 pp. ; III/ (6) ll., 144 pp., (2) ll. Contemporary limp vellum, “Arabic grammar” written in ink on the upper cover, flat spine. Contemporary binding.

I/ « First edition of this Arabic grammar, the first reasoned method composed by a European, Kirsten’s grammar published in 1608 being only a translation of the Al-djarumia, at least as far as the syntax is concerned. – The Arabic passage transcribed in Hebrew and Syriac letters (page 13) was not reproduced in the following editions. » (Bibliothèque de Monsieur le Baron Sylvestre de Sacy, n°2762).

ESTC S116252 ; Madan, I, p.202 ; STC 21350 ; Schnurrer, 49 ; Brunet, II, 1050; Zenker I, 168; Fuck 59 ff.

First edition of the Arab Grammar by Thomas Erpenius (1584-1624), “the first native European to achieve true greatness in Arabic” (Toomer, Eastern Wisdom and Learning, 1996), published in the year he was appointed Professor of Oriental Languages at Leiden.

« For two centuries, Erpenius’ Grammar was the basic book in the study of Arabic, republished without substantial change, but enlarged with all sorts of selected pieces. » (Mélanges de l’Université Saint-Joseph).

From the age of ten, Thomas van Erpenius (1584-1624) studied oriental languages in Leiden.

A famous Dutch orientalist of his time, he published numerous oriental grammars and held the chair of Arabic and oriental languages at Leiden University from 1613 to 1624. A chair of Hebrew was even created in his favour. Courted by the great places of Europe, he never left Leiden. The Grammatica contains fables and wisdoms translated into Latin, with the Arabic text.

“We owe him a grammar for teaching Arabic that one can consider as the first usable in Europe” (Josée Balagna, L’Imprimerie arabe en Occident, Paris, Maisonneuve, 1984, p. 53).

“First edition of the first scientific Arabic Grammar written by a European scholar“. Smitskamp 68b

This work introduced generations of Europeans to the rudiments of Arabic grammar.

II/ First edition.

STC 21350; Madan 18.

Francis Rous entered Broadgates Hall Oxford in 1593 at the young age of 12, afterwards studying at Leyden and the Middle Temple (1601). In 1626 he was elected to Parliament for Truro, where he served for many years. He was an Independent and a member of Cromwell’s Council of State (1653), and a much despised as the provost of Eton College during the Interregnum (1643). Rous’s translation of the Psalms went through many editions.

III/ Rare first edition.

“Crinesius (1584-1629) whose biography is rehearsed in the preface was born in 1584 in Bohemia, the son of a cleric and schoolmaster of the same name and his mother Anna Günther. Educated first in his father’s school, in 1603 he went to Jena and then Wittemberg, and graduated in philosophy in 1607. He then devoted himself to theology and linguistic studies. He married in 1615 Regina Dörffliner, a widow with children. In 1624 he was forced to migrate to Nuremberg, where he taught and ministered. He died around five in the morning on 28 August 1629.

In this work Crinesius, who was the author of several works on Syriac grammar and texts, treats Hebrew as the first or origin of languages, a not uncommon belief, and then goes on to discuss the languages which are cognate with Hebrew or have some validity in the establishment of the scriptural text. He passes on to Samaritan, a chapter on Hebrew vocalization and from this we pass to the other languages stemming from Hebrew – Chaldacan, Syriac, Arabic and Ethiopic, with Persian also discussed. Crinesius tells us he is still a novice in Arabic, but is studying the grammars of Petrus Kirsten of Breslau and Erpenius.

From Crinesius we learn also of a complete interlinear Latin translation of the Qu’ran together with marginal refutations of Muhammadan doctrine, which now ‘needs nothing except a printer, properly trained in the setting of Arabic’…

Unexpectedly there is an interesting account of the pronunciation of French pp. 88-101 with shorter paragraphs on Italian and Spanish, and again the Lord’s Prayer is given. The penultimate chapter is a discussion of the divine name and its forms, and the last chapter is a series of eight scriptural linguistic ‘praxeis’, each one devoted to a different language…

The work includes several sets of liminary verses, including one in Hebrew by Daniel Schwenter, Syriac, Greek and one in Arabic by Zechendorff. This is engraved (not printed) together with some in Samaritan characters by the engraver Herreman, and dated 3 October 1628.

This work, like all the various works on Syriac of Crinesius, is not common”. (Maggs Bros, Further Books from the Library of The Earls of Macclesfield, 2012, n°58).

Precious reunion of three rare first editions bound in contemporary limp vellum binding.