Vredeman de Vries, Jan (1527-1609), Floris, Cornelis (1514-1575) and Galle, Philippe (1537-1612).

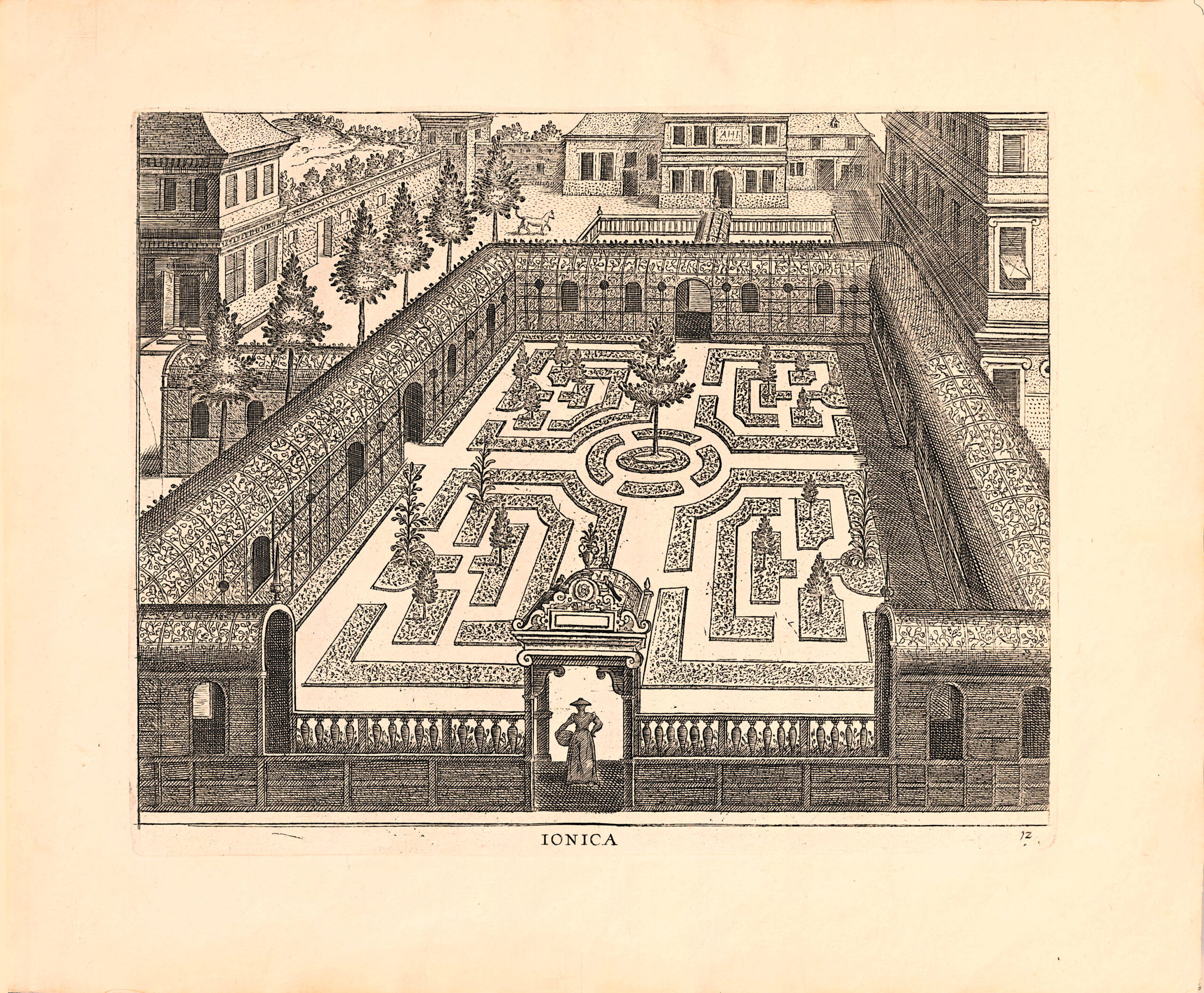

– Hortorum viridariorumque elegantes & multiplicis formae…

Antwerp, Philippe Galle, 1583.

Oblong folio (260 x 323 mm). Frontispiece and 20 numbered engravings of gardens.

First edition.

Berlin Kat. 3390 ; Hollstein XLVIII, 470-490.

– [Bound with] : by the same : Jardins.

Antwerp, Philippe Galle, c. 1583. 6 numbered engravings.

First edition.

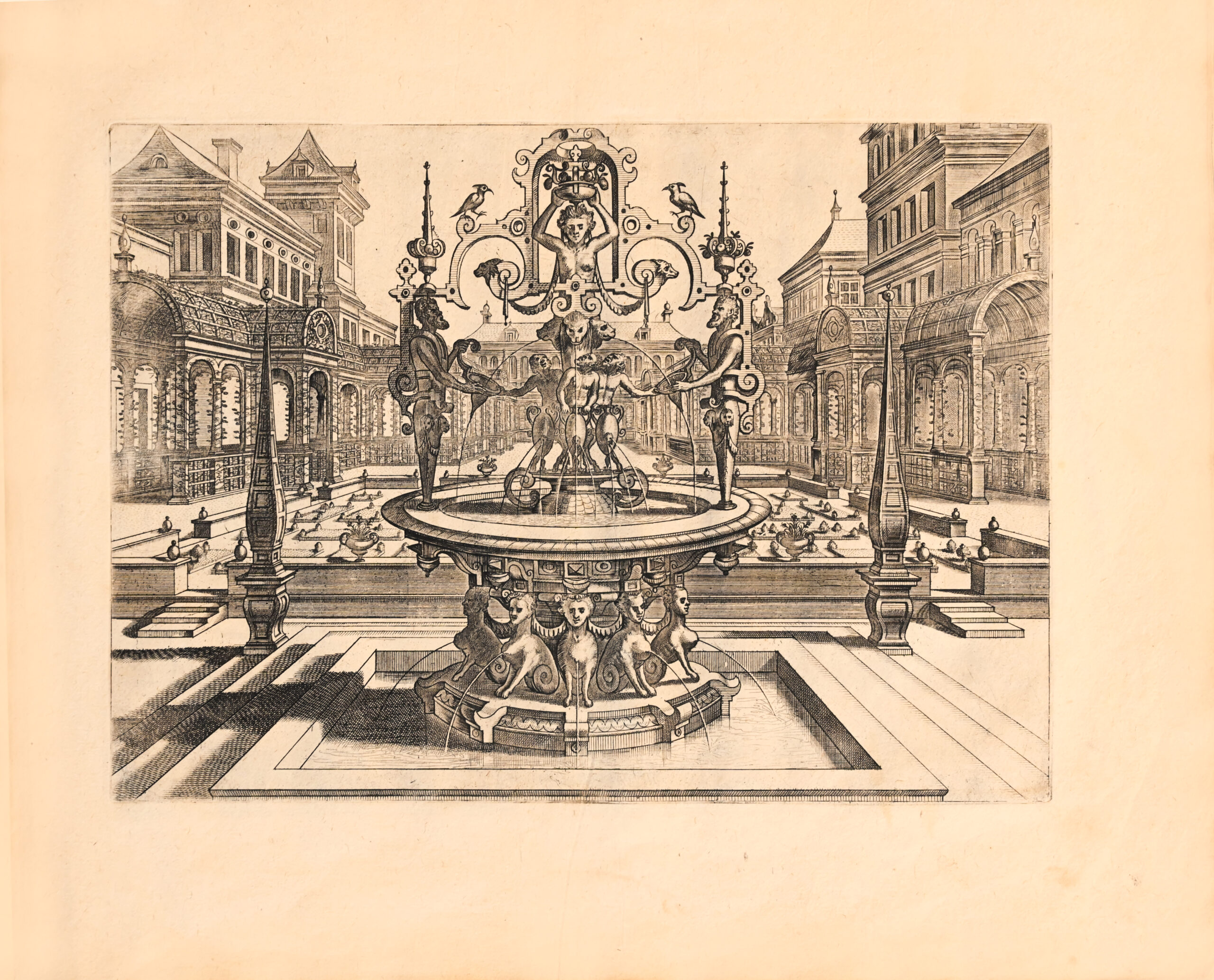

– [Bound with] : by the same: Artis Perspectiuae plurium generum elegantissimae Formulae, [graphic], multigenis Fontibus, nonnullisq[ue] Hortulis affabre factis exornatae, in cõmodum Artificum, eorumq[ue] qui Architectura, aedificiorumq[ue] cõmensurata uarietate delectantur, antea nunquam impressae.

Antwerp, Gerardus de Jode, 1568. Frontispiece and 17 engravings.

First edition.

– [Bound with] : by the same : Puits et fontaines.

Antwerp, Philippe Galle, 1573. 24 numbered engravings on 12 leaves, tiny tear to one plate.

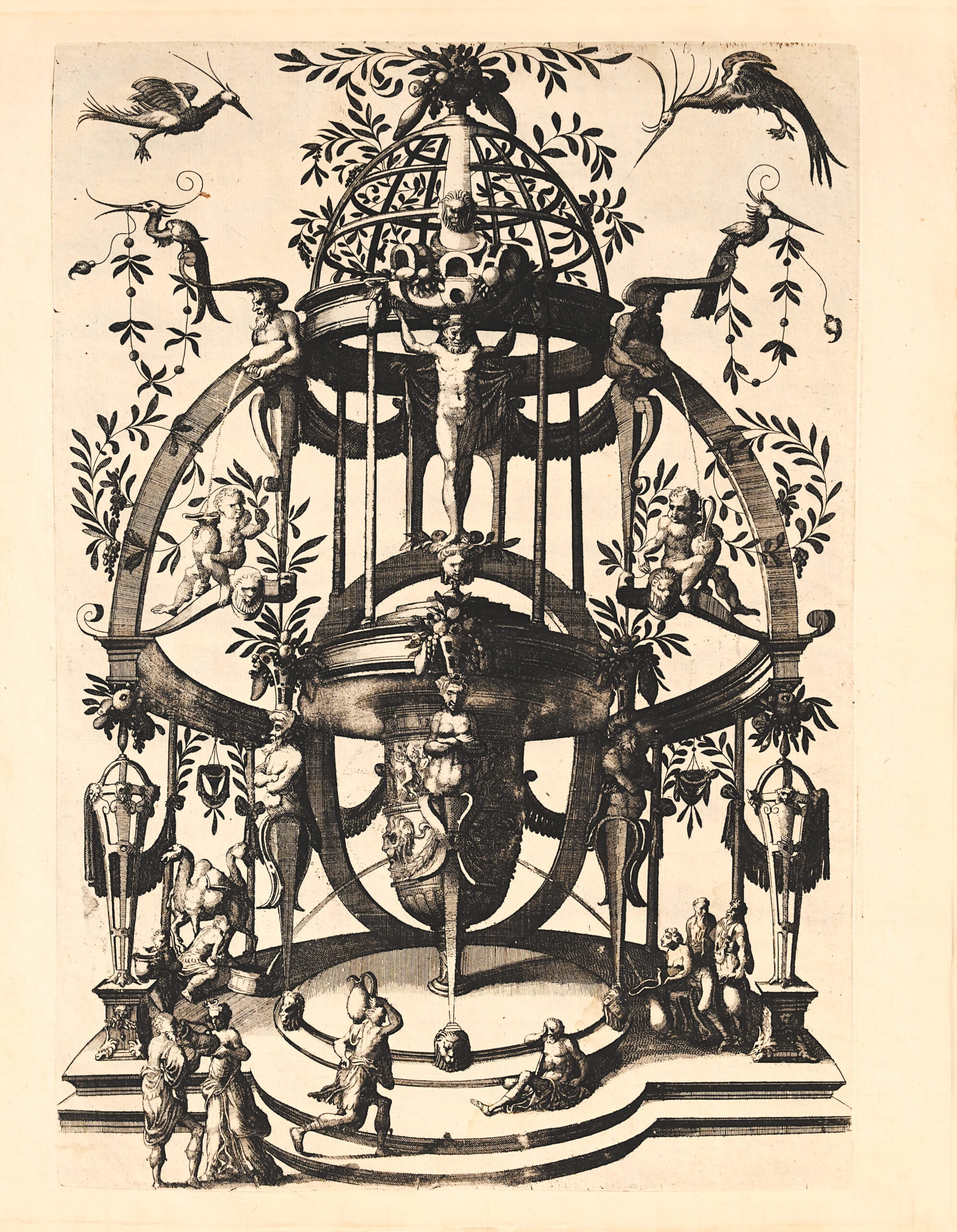

– [Bound with] : Floris, Cornelis. Veelderleij niewe inventien van antijcksche sepultueren diemen nou zeere ghebruijkende is met noch zeer fraeije grotissen…

Antwerp, Jerôme Cock, 1557.

Title and 15 engraved plates showing fantastic decorations, and funerary monuments in the grotesque style.

Very rare first edition.

Bound in antique vellum, endpapers renewed. Title of the first suite rubbed and chipped with marginal tears and fold and joint to endpaper; stains to some plates.

257 x 326 mm.

“Important album of 5 suites of 16th century Dutch engravings by Vredeman de Vries et Conerlis Floris comprising 3 engraved titles and 82 engravings of gardens, fountains and wells, and grotesque tombs. All bound in an old parchment binding ».

Rare first edition of this series of 20 plates of gardens associated with the Doric (6), Ionic (7) and Corinthian (7) orders: parterres, alleys, courtyards, with beautiful buildings in the background. Attractive engraved title on a floral architectural background. The engraver has not been identified.

Some of the plates have later been copied by Hans Puechfelder and are used in his work on gardens, published in 1591.

“An open-air cabinet of curiosities.

Nature, guided by Divine Providence, is admirable in that it includes so many kinds of animals and plants under the connection of the heavens, on the surface and extent of the earth. Vegetables and plants, with regard to the various parts of the world and provinces, the number cannot be expressed, & in such a multitude & heap there would be confusion, were it not that human art & industry, to perfect Nature has excogitated various compartments & beds in the shape of crosses, roses, hearts &c. sometimes separated, sometimes intermingled, to house said plants, as in chambers & places of reserve.” Daniel Loris, Le thrésor des Parterres de l’univers, 1629.

In Le thrésor des Parterres de l’univers, Daniel Loris, physician to the Dukes of Württemberg, invokes the need to perfect nature by compartmentalising space and designing garden “rooms” and “storerooms” to house a collection of remarkable cultivated plants. A “programme” for “ Jardins de plaisir, tracés en compartimans, & garnis de plantes, & arbres curieux s” is given, similar to that for cabinets of curiosities. The German word Wunderkammer means “chamber of wonders” and refers to the collections of the princes of Europe from the 1560s and 1570s onwards, based on a renewed interest in antiquity, the natural sciences and geography.

The organisation of the garden, as seen in particular in the works of du Cerceau, is clearly based on a composition with one or more vanishing axes. But this perspective does not unify the surface of the garden in a completely linear fashion. The juxtaposition of parterres, like the paving in Serlio’s scenes foreshadowed by the paintings of the quattrocento, compartmentalises and sequences the garden space. Book IV of the Regole generali di architettura published in 1537 includes six illustrations of parterres, four broken tiles and two mazes. Serlio produced the earliest surviving models for the compartmentalisation and ornamentation of gardens. In fact, he was interested in the scenography of these spaces, as he wrote:

Li giardini sono ancor l’oro, parte de l’ornamento della fabrica, per il che queste quatro figure differente qui sotto, sono per compartimenti d’essi giardini, ancora che per altre cose potrebbono seruire, oltra li dua Labirinthi qui adietro che a tal proposito sono.

Also the Renaissance garden, a theatrical place a fortiori, is a scene of perspective illusion. In this “ideal site”, this microcosm, a fictitious space unified by “perspective construction”, everything, even the most curious, can find its place.

The first botanical gardens were created in the mid-sixteenth century and grew in number over a relatively short period. The invention of botanical gardens was the result of a project to ” educate the eye “, based on a scenographic device. Daniele Barbaro, one of the designers of the Horto de’i simplici in Padua (1545), was a translator of Vitruvius. In La Prattica della Perspettiva (1569), he also reflected on scenography as an artificial perspective; but it is not this stage effect that dominates in Padua. The garden is enclosed within a circle 84 metres in diameter, symbolising the universe. Inside the circle is a square divided into four Spaldi, representing the four continents from which the plants originate. Seen from a bird’s eye view, the Spaldi offer a profusion of shapes and colours created by the characteristic fragmentation of the Parterre de carreaux rompus – so named by Charles Estienne in La Maison rustique (1583). In fact, the cultivated plot drawn from a “pourtraict” becomes a garden ornament. But in Padua, the parterre is not just an element of decorative garden architecture. The particular and varied shapes of the Compartments help to identify and situate the spaces. In this way, the scenography would visually codify the location where a particular plant is grown and facilitate botanical learning based on plant identification; it could be a form of Art of Memory or method of place. The layout developed in Padua was to be found in almost all the botanical gardens founded in the 16th and 17th centuries. The forms developed in these institutions are the models for most gardens of medicinal plants and curious plants.

The success of these “earthen theatres” encouraged the creation of private collections. According to Claudia Lazzaro, these spaces, called giardini variati by Ulisse Aldrovandi, differed from the giardini volgari and the purely practical medicinali. Agostino del Riccio recommended following the model of the Florence plant garden for planting exotic and new plants. A series of plates produced for the botanical garden in Pisa includes some models of flowerbeds that exactly repeat Serlio’s designs. According to Lucia Tongiorgi Tomasi, this example shows the transfer of the institution to the aristocratic garden. In fact, this compilation formed the basis of another series of drawings by Bartholomeus Memkins, intended for the garden of the Elector Palatine Ludwig VII of Bavaria, a lover of rare plants. Memkins proposed growing a single plant on each bed of the compartment. The work of Lucia Tongiorgi Tomasi and Ada Segré has shown the detailed composition of the flowerbeds.

During the relevant period, several treatises on architecture, agriculture and horticulture – Serlio (1537), Estienne (1584), de Serres (1600), Vinet and Mizault (1607), Lauremberg (1631-2) and Ferrari (1633) – include plans for the design of flowerbeds. A collection of garden designs by Hans Vredeman de Vries (1587) remains a precious source of inspiration. The only known genuine book of designs, written by Daniel Loris in 1629, contains a series of more than two hundred motifs. The compositions are complex, refined and often “unnatural”, sometimes denying the regular order of artificial perspective. These modules, juxtaposed on the scale of the garden, and the virtuosity of the layout certainly converted a certain repetitive aspect into a profusion of shapes and colours, a probable allegory of “the germinating power of nature”. The multiplicity of perceptible elements was also intended to erase and dissolve the design of the motifs into the mass. In fact, the compartmentalisation of rare plants grown on chaotically shaped boards into tiles is also, as a “serial process”, an excessive phenomenon. Was compartmentalisation, a key tool of rational thought, subverted by the Mannerist movement?

Comparing a garden with different flowers and figures.

During the second half of the 16th century, flower arrangements were certainly characterised by their lightness. The flowers, still very similar to their wild relatives, were relatively discreet in both size and abundance. To sum up, flowerbeds evolved from the Préau, of medieval origin, to the parterre of bulbs of the early years of the 17th century. In the 1550s, wreaths and bouquets of wild flowers were still being made in split-tile courtyards. The “mil fleur” or “esmaillé” effect, evoked here by Maurice Scève and elsewhere by Ronsard and Catherine des Roches, was appreciated:

Les jardins agencer en maints lieux tournoyés

De promenoirs croisés de berseaux voutoyés,

D’herbes, plantes, semés communes, & satives,

Et odorantes fleurs de mille couleurs vives.

About the last suite, by Cornelis Floris: « These panels belong to a series of sixteen diverse ornament and tomb designs after drawings by one of the most prominent architects and sculptors in the Netherlands at the time, Cornelis Floris. Floris drew inspiration from the grotesque ornamentation unearthed in Roman ruins and from the work of contemporary Italian artists influenced by the motifs. These lighthearted inventions were intended to inspire craftsmen and artists”. (Met Museum).

Exceptional wide-margined set of 5 rare and very rare first editions illustrated with eighty-two 16th century engravings on gardens and their embellishment : wells, fountains etc…

Provenances: Rothschild; Baron Alexis de Rédé.