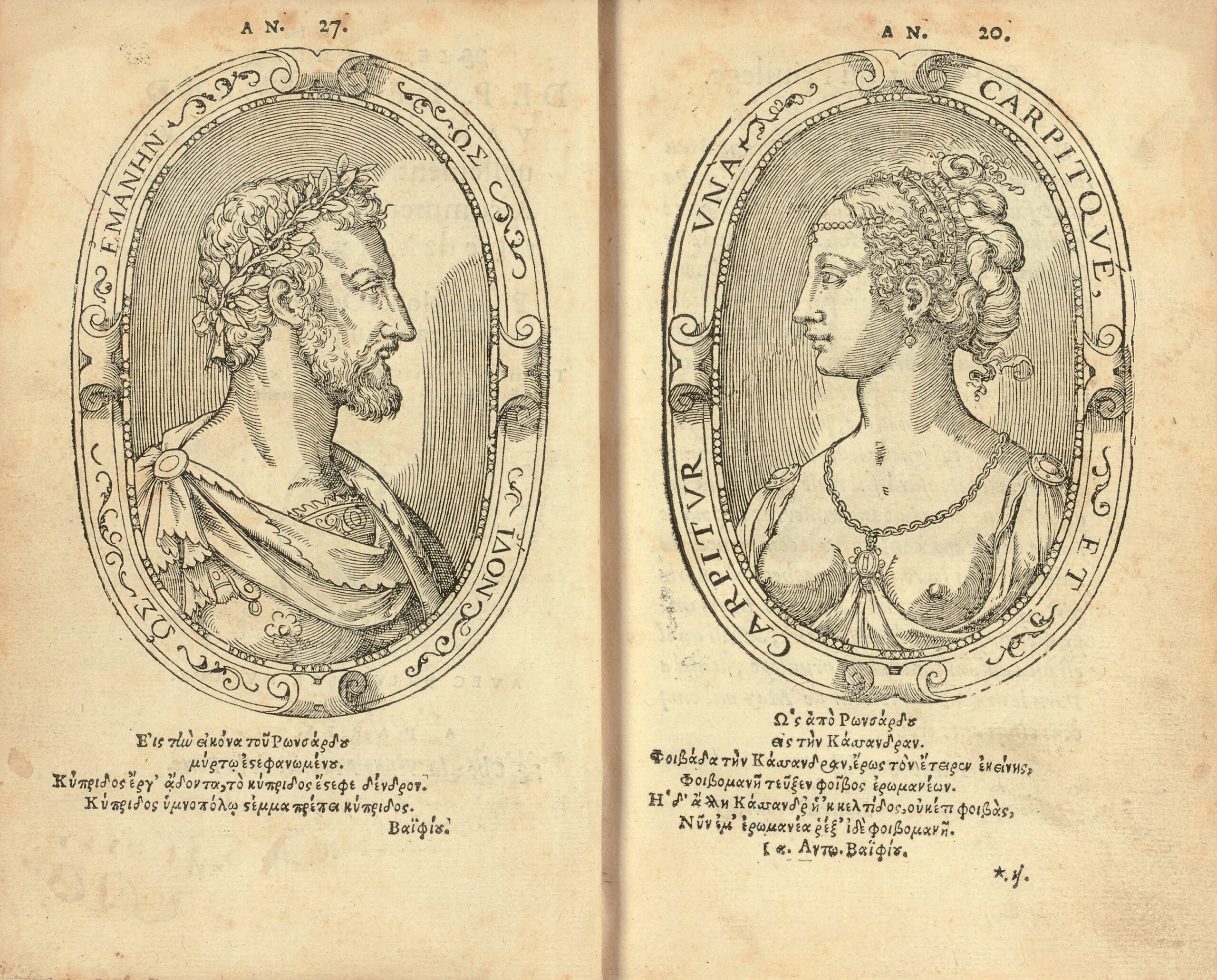

Paris, veuve Maurice de la Porte, 1553.

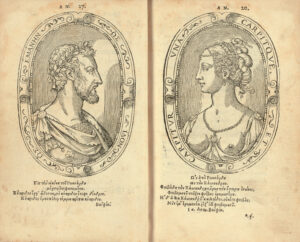

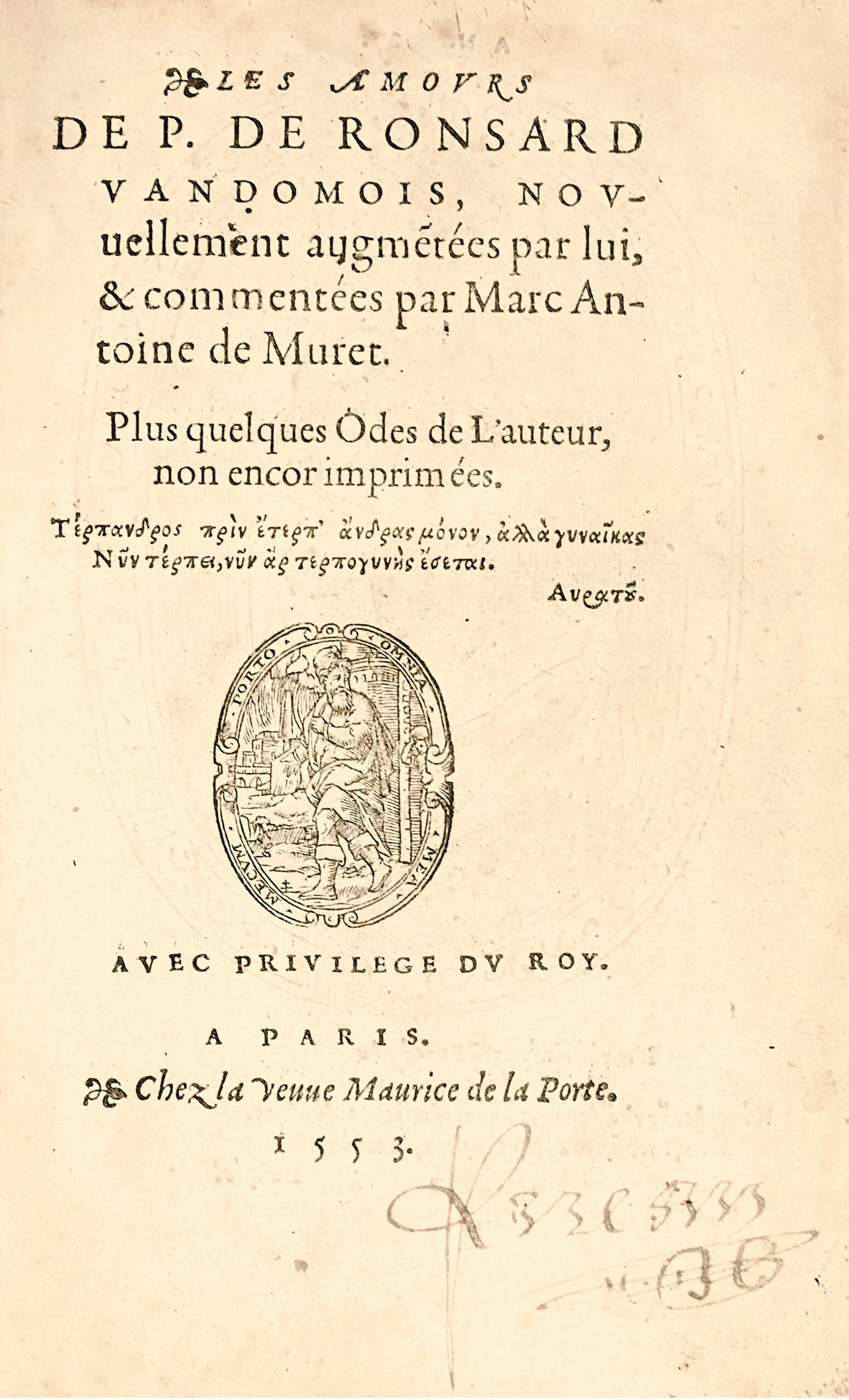

8vo of (8) ll. with 3 bust portraits: Ronsard, Cassandre and Muret, 262 pp. (wrongly numbered 282), (1) l. Full granite-like brown calf, blind-stamped fillet around the covers, richly decorated ribbed spine, upper joint restored, red morocco lettering-piece, red sprinkled edges. French seventeenth century binding.

156 x 96 mm.

Second original edition, second state (out of three) of Ronsard’s major work.

It was in this edition that appeared for the first time the famous Ode à Cassandre : ” Mignonne, Allon Voir si la Rose “, one of the most beautiful poems of Western literature (page 266).

J.P. Barbier, Ma bibliothèque poétique, II, pp. 36-41; Tchemerzine, V, 421; A. Péreire, Bibliographie des œuvres de Ronsard ” Bulletin du Bibliophile “, 1937, pp. 352-360.

“This delightful odelette is perhaps the most famous of the Vendôme poems… Ronsard placed it at the end of these ‘Amours’, as one would place a particularly fine line at the end of a sonnet. The whole collection is enhanced by being so wonderfully closed“. J. P. Barbier.

The first edition was published the previous year, in 1552.

The 1552 collection contains 183 sonnets, a ‘Chanson’ and an ‘Amourette’.

It was a great success and was reissued seven months later, reduced by two sonnets, increased by 39 other unpublished sonnets, a “Chanson” and four odes, and accompanied by a very exhausted commentary which the humanist Marc-Antoine de Muret had composed to make Ronsard’s erudition within the reader’s reach.

“In this edition of the “Amours”, printed in 1553, is the sonnet that Mellin de Saint-Gelais addressed to Ronsard after their reconciliation. (Brunet)

“This second edition of the ‘Amours’ is precious, not only for the unpublished sonnets and pieces it contains, but also because it includes two famous works: the Voyage aux Iles Fortunées, and above all the Ode à Cassandre ‘Mignonne, allonson voir si la rose… ‘. And then there is Muret’s commentary, also unpublished, which in one fell swoop placed the 29-year-old poet in the ranks of the classics, since his work deserved to be fully explained to uninformed readers, who might have been confused by so many novelties and such clever mythological allusions.”

Jean-Paul Barbier.

This collection was inspired by a real woman, Cassandre Salviati, the daughter of a Florentine banker living in Blois. Ronsard met her at a court ball in 1545. She married shortly afterwards, no doubt escaping the poet’s grasp.

“’Les Amours’ should not be read as an autobiographical work, but as the diary of a dream love life. This work belongs to the emerging fashion for Petrarchan “canzoniere”. In other words, the love project is lofty, ambitious and sometimes desperate. Following in the footsteps of the courtly tradition, the lover sees the belle as an absolute being, a place of beauty and delight, but also a place of cruelty that can manifest itself without justification. He is torn between admiration, obedience and reproach. Such a material requires a “lofty” style, rich in figures, in which Ronsard often shows himself to be a great poet rather than a precious imitator. The ‘Amours’ are also indebted to the tradition of Finician Neoplatonism: love is one of the ‘fury’ that allows the soul to rediscover the One, its place of origin; in serenity, the woman leads the lover to Beauty. But for Ronsard, these sublimated inspirations are not without a counterpart. Violently sensual, Cassandra’s lover is one of the rare Petrarchan poets to claim the rights of the flesh. He used unequivocal language and daring images.

To define ‘Les Amours’ of 1552-1553 as abstract, precious and conventional is to have read them only on the surface. On the contrary, they reveal a mad lover, in a hurry to break with the introversion that the transient suitor loved: wild poetry under a cloak of pomp.”

The original edition of 1552 is very rare and very difficult to find in its original condition. As a result, enthusiasts are content with copies in modern bindings.

The second original of 1553 “in antique binding” is also very difficult to find.

Printed in italic script for the verse and Roman script for the prose, this elegant edition is illustrated with fine woodcut portraits of Ronsard, Cassandre and Muret.

“The woodcut portraits of Ronsard and Cassandre, with Greek verses by Baïf on the bottom, generally attributed to Jean Cousin, were in fact drawn by Nicolas Denisot (see the poem addressed to him by Ronsard on p. 210) They were already printed in the first edition of 1552 and are regarded as the first example of an effigy of a living poet portrayed cheek by jowl with his love”.

A precious copy preserved in its 17th century French binding in granite-like brown calf.