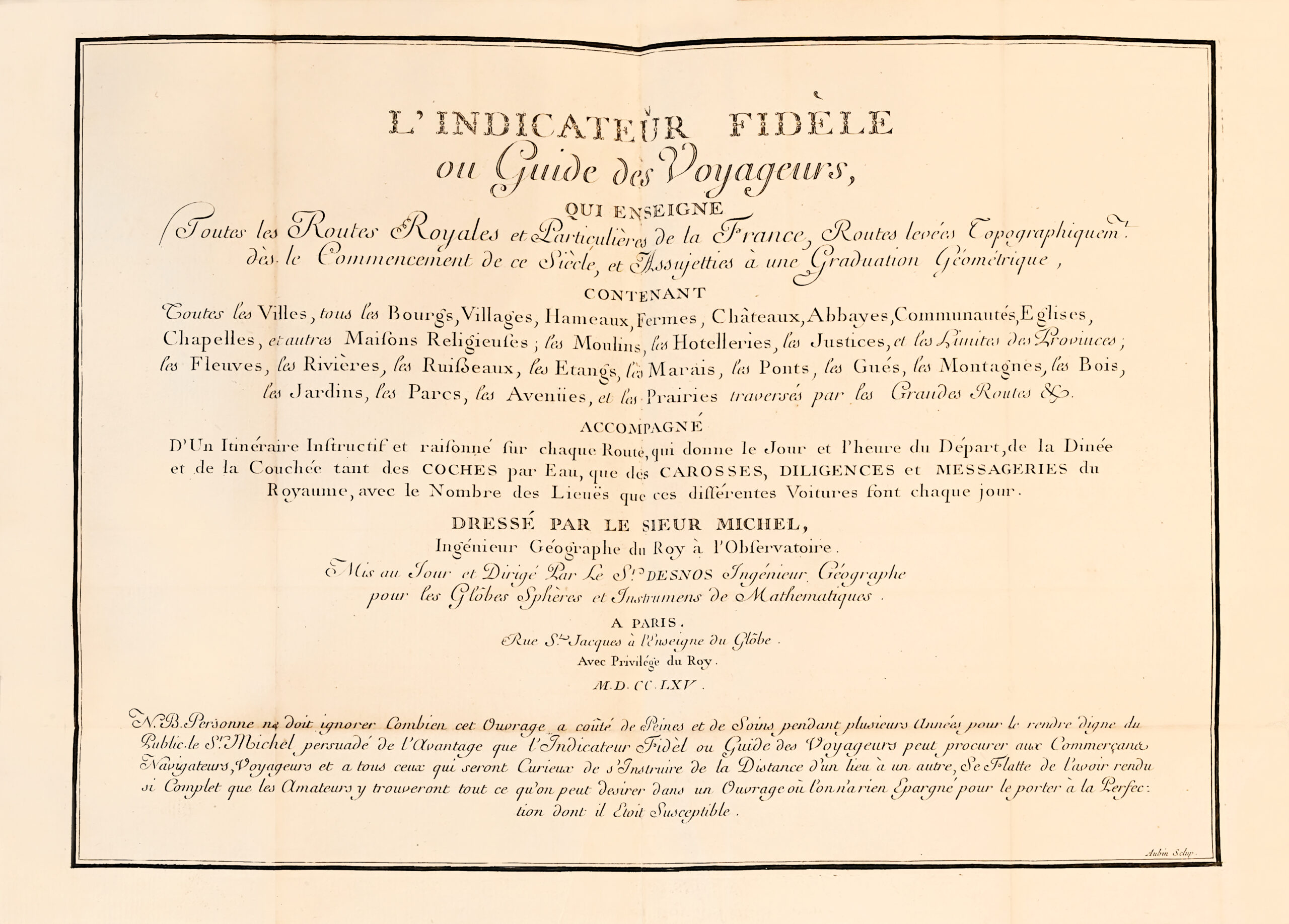

A Paris, Rue St Jacques, à l’Enseigne du Globe, 1765.

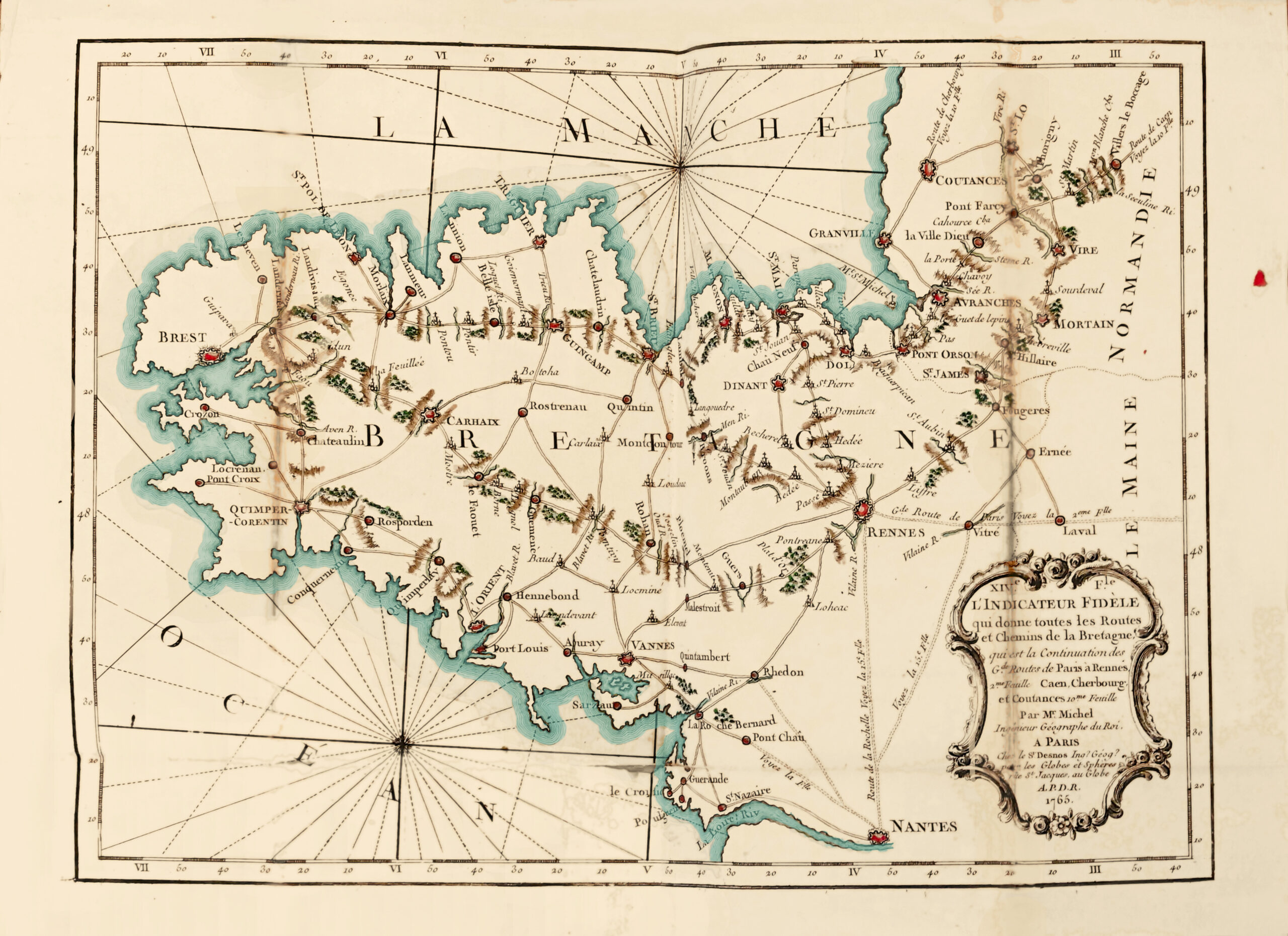

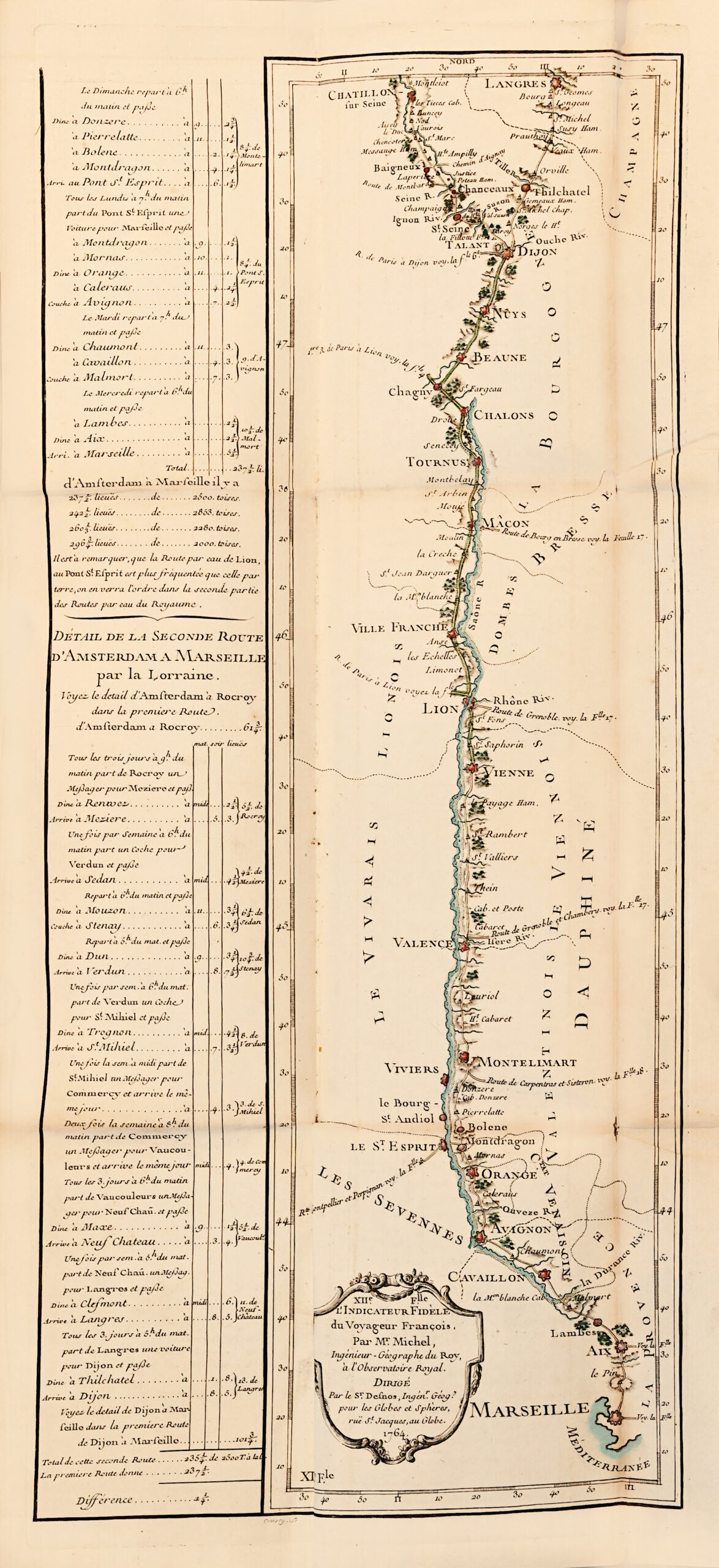

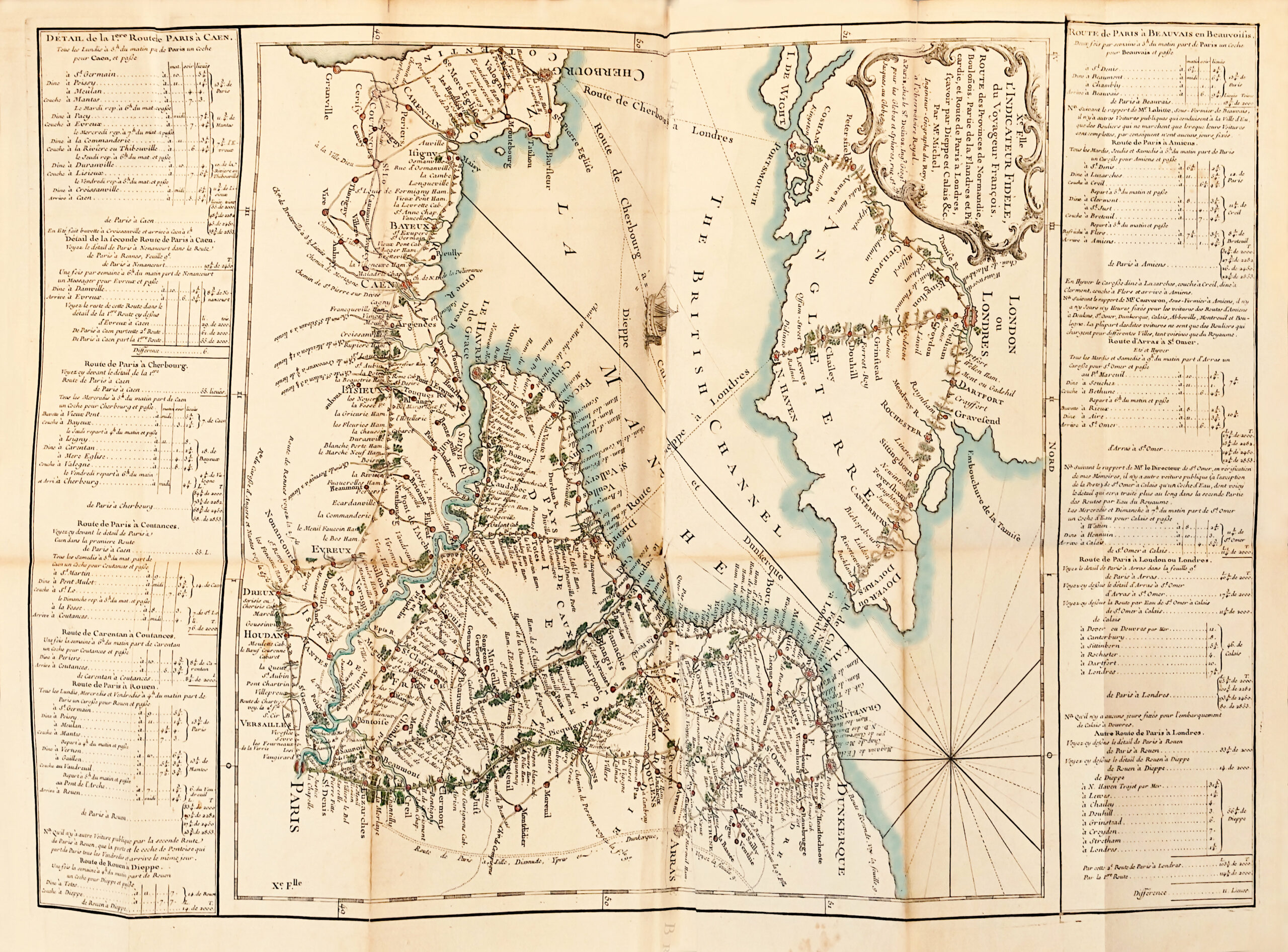

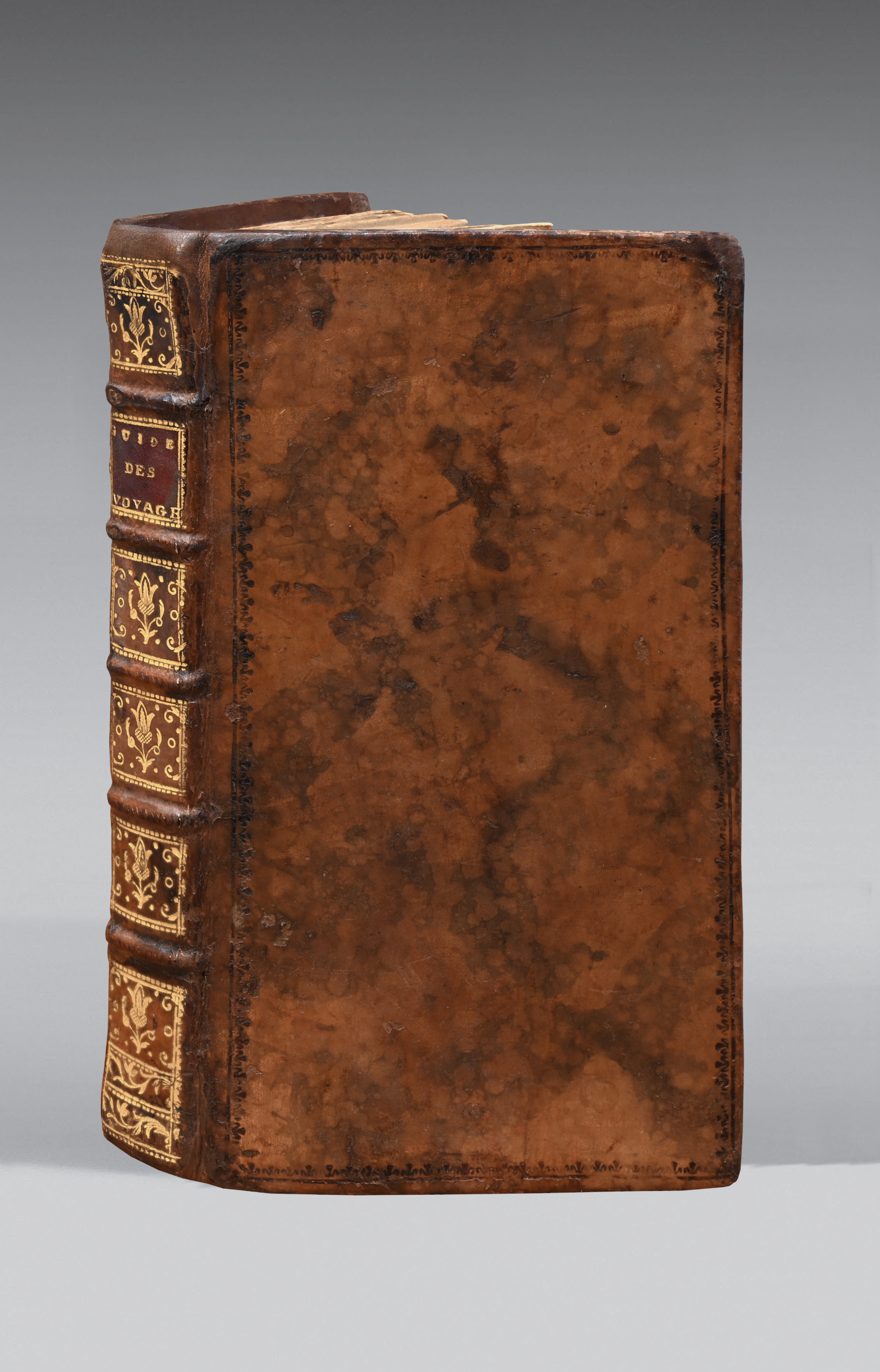

8vo: title engraved by Aubin, dedication to Cassini de Thury engraved after Baisiez, 19 engraved and watercoloured maps: outlines highlighted, red dots for the cities, oceans and flowers in green. 1. general map of France; 2. suburbs of Paris with ‘grandes routes branchées sur Paris’ and mineralogy of the Paris region (numbered 1); 3. From Paris to Nantes, (numbered 2); 4. From Paris to Bordeaux and Toulouse, fold-out map (num. 3); 5. From Paris to Lyon through Burgundy and Bourbonnais (num. 4); 6. From Paris to Strasbourg (num. 5); 7. Roads of Champagne, Lorraine… (num. 6); 8. Third road from Paris to Strasbourg [via Soissons] (num. 7); 9. Third road from Paris to Strasbourg… [via]… Langres (num. 8); 10. Roads of the Provinces of Picardy (num. 9); 11. Road from Paris to London…, folding map num. 10); 12. Road from Amsterdam to Marseille (num. 11); 13. Second part of the Road from Amsterdam to Marseille… fold-out map (num. 12); 14. Great Road from Strasbourg to Vienne (n. n.), fold-out map; 15. Roads and paths of Brittany (num. 14), the ocean is only slightly tinted; 16. Roads and paths… comprised between the 4 great roads from Paris to Nantes, Rennes, Toulouse, Bordeaux (num. 15); 17. Continuation of the western and southern roads (num. 16); 18. Roads and paths… between the two main roads from Pans to Toulouse (num. 17); 19. Continuations of the Western and Southern roads from Pans to Marseille (num. 18), the sea is tinted green; Prospectus du Guide des Voyageurs pour les Routes Royales (2 pp.); Alphabetical catalogue of the Supplement (10 pp.). Marbled calf, decorated ribbed spine. Contemporary binding.

210 x 113 mm.

First edition.

“We reproduce the N.B. at the bottom of the title which indicates the care that went into the making of this work:

‘No one should ignore how much pain and care this work has cost over several years to make it worthy of the public. The Sr. Michel, convinced of the advantage that the Indicateur Fidèle ou Guide des Voyageurs can bring to merchants, navigators, travelers and all those who are curious to learn about the distance from one place to another, is proud to have made it so complete that enthusiasts will find everything they could wish for in a work in which nothing has been spared to bring it to the perfection of which it was capable.

The title is followed by a beautiful frontispiece containing the dedication: ‘A Monsieur Cassini de Thury…’. At the head, the arms of M. Cassini de Thury; at the bottom, a water coach drawn by horses, a stagecoach, monuments and landscapes in the background; the whole framed by trees and rocks.

The volume contains a general map and 18 road maps, with a legend in the margin indicating distances and departure and arrival times. It ends with a Prospectus or Travellers’ Guide and an alphabetical catalogue of royal and private roads. (Bulletin de le Société archéologique…, vol. 2, 1905).

“There is no traveler who is a little curious about his route who does not, before venturing out, go and buy a Joanne, a Badeker or, at the very least, an Indicateur Chaix. This is a wise precaution, so wise in fact that our fathers, who were no more misguided than we are, also had their Guides, and these Guides provided a wealth of useful information. We have found the Atlas whose title follows, scrupulously respecting the wording: ‘L’Indicateur fidèle ou Guide des Voyageurs, qui enseigne Toutes les Routes Royales…, Paris, 1765’. It’s a long title, but how suggestive it is! L’Indicateur Fidèle is remarkably engraved; it is a conscientious and artistic work. It is both picturesque and accurate. Woods, rivers and coastlines are highlighted with green, blue and bistre tints. It is true that it had its price; for the 4to copy sold for 15 livres, and each road independently, on a separate sheet, was worth 15 sous”. (Le Magasin pittoresque, vol. 61, p. 206).

The French network was in a sorry state at the beginning of Louis XV’s reign. All the accounts of the time are unanimous on this point, and Marie Leczinska’s arduous journey through the eastern provinces to reach Paris in 1725 was the best illustration of this. With the steady development of overland transport, road maintenance increasingly appeared to be an insoluble undertaking, a sort of endless patching up that was always carried out at the last extremity and then almost immediately cracked again.

This chronic rescue situation, which made the kingdom’s roads the worst bottleneck for the administration and for a booming economy, could not continue indefinitely.

While ordering the gradual repair of all the major roads in the kingdom, starting with those used by the postal service, the Controller General Orry, and with him the Intendant Trudaine, decided to create entirely new roads wherever the political and economic necessities of the time demanded. In the middle of the 18th century, they therefore envisaged the creation of what we might now call a network of ‘horse roads’, and decided that this network should be capable of supporting regular galloping traffic. The decisions behind this patient but far-reaching transformation of France’s main roads are well worth remembering: the ‘corvée des chemins’, which was made compulsory throughout the kingdom by the Instruction of 13 June 1738 issued by the Controller General Orry, was the prerequisite for the entire operation, since it was intended to provide the Ponts et Chaussées engineers in each province with the enormous, if not highly efficient, workforce they needed.

The same instruction instructed the engineers, in agreement with the provincial intendants, to start work and draw up plans for the roads to be opened or aligned. Their greatest effort, which it was hoped would be definitive this time, was of course to focus on the major routes from the capital: above all, the government’s orders had to be able to reach the remote provinces more quickly and safely across this vast kingdom of France.

In addition to this absolute priority for a large centralized network, each engineer would seek to improve the roads leading away from the capital of his generality, and particularly those leading to the capitals of neighboring generalities. Finally, work would also be carried out on a few cross-country roads of great economic or strategic interest.

Daniel-Charles Trudaine, appointed to the Ponts et Chaussées department in 1743, was to give a vigorous impetus to the whole enterprise. Later followed by his son, he coordinated the work of the engineers with authority and ensured that they were recruited and educated to a higher standard.

In 1744, the first thing he did was to set up an office of draughtsmen in Paris, the office of the geographer Mariaval, to ensure that the road plans drawn up by the engineers were in order. On 14 February 1747, he appointed Jean-Rodolphe Perronet, whom he had brought from the Généralité d’Alençon, as head of the office and gave him the task of training future sub-engineers. Finally, in 1750, just as the first students were leaving what would later become the École des Ponts et Chaussées, Trudaine reorganized the corps of engineers. Everything was now in place for the start of the largest public works program ever undertaken in France.

This Indicateur fidèle ou Guide du voyageur, a real bestseller, offers an attractive look at 18th century France. Its roads were organized; the country was administered. The great work of building a modern road network bore fruit here.

From the Maurice Lecomte library.