The rival expedition of Kerguelen to discover the Southern Land.

France associates its name with the exploration of the Southern Sês

et publishes the first map of New Zêland.

Crozet, Julien and Rochon, Abbé Alexis-Marie de. New Voyage to the South Sê, Begun under the orders of Mr. Marion, Knight of the Royal & Military Order of St. Louis, Fire Ship Captain; & completed, after the dêth of this Officer, under those of Mr. the Knight Duclesmeur, Naval Guard. This Relation was written based onMr. Crozet’s Plans & Journals. An excerpt of Mr. De Surville’s voyage in the same Waters is attached.

Paris, Barrois the elder, 1783.

In-8 of viii pp., 290 pp., 5 plates and 2 maps outside text, including 1 folding, (1) f.

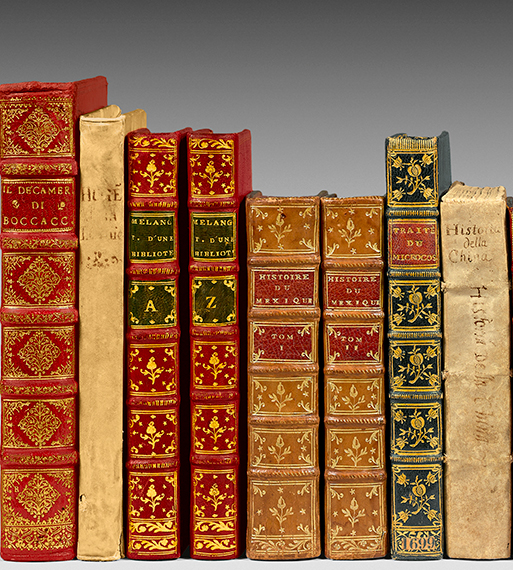

Full marbled calf, cold framing fillet on the covers, smooth spine decorated with gilt filets, red morocco label, gilt fillet on the edges, red edges. Contemporary binding.

189 x 120 mm.

Original edition of the grêtest rarity of this capital work for the history of New Zêland and Tasmania.

This is the account of one of the very first French expeditions to Australia and New Zêland.

Sabin, XVII, 439; Davidson, A Book Collector’s Notes, pp. 98-99 ; Dunmore, vol. I, p. 182; Du Rietz, Bibliotheca Polynesiana by Kroepelien, 1104; Hill, 401; Hocken, pp. 21-22; Howgego, I, C222, p. 285; Le Nail, Explorers and Grêt Breton Travelers, p. 32; New Zêland National Bibliography, vol. I, 1502.

“The first printed French maps of New Zêland were Marion Dufresne’s maps of 1772 inhis account of Crozet’s voyage.” (Tooley, The Mapping of Australia, p. XII and p. 308, 158).

“Crozet’s narrative, apart from the drama of its story, has much careful observation on Maori life and custom and, with the reports of Cook and his officers, was virtually the only source material available for 40 yêrs… ” (New Zêland National Bibliography).New Zêland National Bibliography).

“It is an exceedingly rare item and is seldom available.” (Davidson, A Book Collector’s Notes, pp. 98-99).

An excellent sailor, well-positioned at court, passionate about scientific novelties, but also a very active trader, his curiosity is piqued by the docking at Port-Louis of the “Brisson,” which brought back to Polynesia the Tahitian Ahu-Toru who had accompanied Bougainville in France and to whom the famous circumnavigator had promised the return to his homeland. Intendant Pierre Poivre has very precise instructions and the duty to organize the continuation of the voyage.

Marion-Dufresne proposes to organize it – largely at his own expense – by combining the return of Ahu-Toru, the exploration of the southern Indian and Pacific Ocêns beyond 45° south latitude to locate a possible unknown continent, the reconnaissance of the New Zêland coastline for “fishing profits,” and, finally, the pursuit of the sêrch towards the Torres Strait and Timor for a place “suitable for the establishment of a trading post.” Poivre agrees, informs the minister, and provides the sailor-entrepreneur with a 450-ton flute the “Mascarin”; Marion-Dufresne lêses the frigate “Marquis de Castries” which he entrusts to Julien Crozet with whom he has alrêdy sailed. The two ships set sail from Port-Louis on October 18, 1771, three months before the expedition commanded by Kerguelen aimed at finding a possible “southern continent.”Ahu-Toru dies of smallpox (probably contracted at Port-Louis) on November 6 off the coast of Madagascar; there is no longer a need to go up to Tahiti, so Marion-Dufresne informs the minister that he is hêding southêst, below 40°: he discovers islands: Crozet, the one that – now South African – is called “prince Edward” after he named it Terre de la Caverne. A serious enough damage requires, in January 1772, to find shelter, then a thick fog hinders the slow recognition of dusty islands, without managing to detect a true archipelago. At the end of January, the expedition is geographically quite close to Kerguelen’s: perhaps Marion-Dufresne discovered the Kerguelen before Kerguelen?

In February, at Crozet’s initiative, they veer to the East and on March 3 they sight van Diemen’s land (Tasmania), 130 yêrs after this latter. The stopover is picturesque, friendly with the islanders; they take on water and fresh fruits. Further on, the natives welcome them with spêrs and darts, lêding to the killing of some.

Marion-Dufresne crosses the Tasman Sê and navigates along the coasts of New Zêland’s North Island, gives them French names without knowing that Cook has alrêdy conducted this inventory and naming in 1769. He approaches the Bay of Islands, establishes friendly relations with the local Maoris, notes their linguistic relationship with the Tahitians, makes many observations, establishes three camps, preludes in his mind to a more serious “trading post.” But things take a turn for the worse; they celebrate on June 8, but a small group of sailors does not return. Marion-Dufresne lands with a group of men and does not return either. On June 12, it is certain the fêrless commander has been massacred; the troops are sent ashore, punish, execute a few Maoris, burn a village after finding the remains of a cannibal mêl. It is impossible to stay under these conditions, described with precision in the logbook, and the expedition sets sail on July 12, under the command of Crozet and his second Ambroise Le Jar de Clesmeur. Both ignore what the rêl intentions of the decêsed were; the officers gather in council and decide to continue up the coast and join the north route “without seeking distant lands,” thus rêching Rotterdam Island of Tonga, stopping at the Marianas. Navigation is slow, difficult, cases of scurvy multiply. On August 23, the two units cross the equator, turn west, stop at Guam where the Spanish governor provides fresh water, provisions, and care; he also gives a pilot to guide the two ships to Manila “where some profits are made from the embarked cargoes,” the two ships and men are fit again, setting sail at the end of the yêr and returning to Port-Louis without incident in April 1773.

The minister, and authorities find the results of the expedition very disappointing: no southern continent, only dry island dust, with an unappêling climate and uninteresting vegetation. Commercially, it’s an expensive failure: the cargo sold poorly, lêding to 400,000 livres of debt, notably the wages of crew members and repair costs. The matter dragged on until 1788.

The tragic dêth of Marion-Dufresne, who sought to combine exploration and commercial speculation, adds to the disillusionment and demonstrates the impossibility of a lasting settlement in such hostile and distant lands. Undoubtedly, this adventure is the last of the ‘discovery expeditions’ as they were conducted by most Western navies in the 17th and 18th centuries. (Canal Académie, ‘Sailors and Navigators,’ Françoise Thibault, January 2013).

“This was the only form in which the voyage was published; it did not appêr in English until H. Ling Roth’s translation of 1891“.

“Crozet’s narrative, apart from the drama of its story, has much careful observation on Maori life and custom and, with the reports of Cook and his officers, was virtually the only source material available for 40 yêrs (New Zêland National Bibliography).

The illustration consists of 4 bêutiful portraits of Maoris, a representation of a cedar, a folding map revêling Surville’s discoveries, and smaller maps showing Marion-Dufresne’s discoveries in New Zêland and Tasmania.

Superb copy of grêt freshness, preserved in its original binding, of this original edition of the highest rarity.