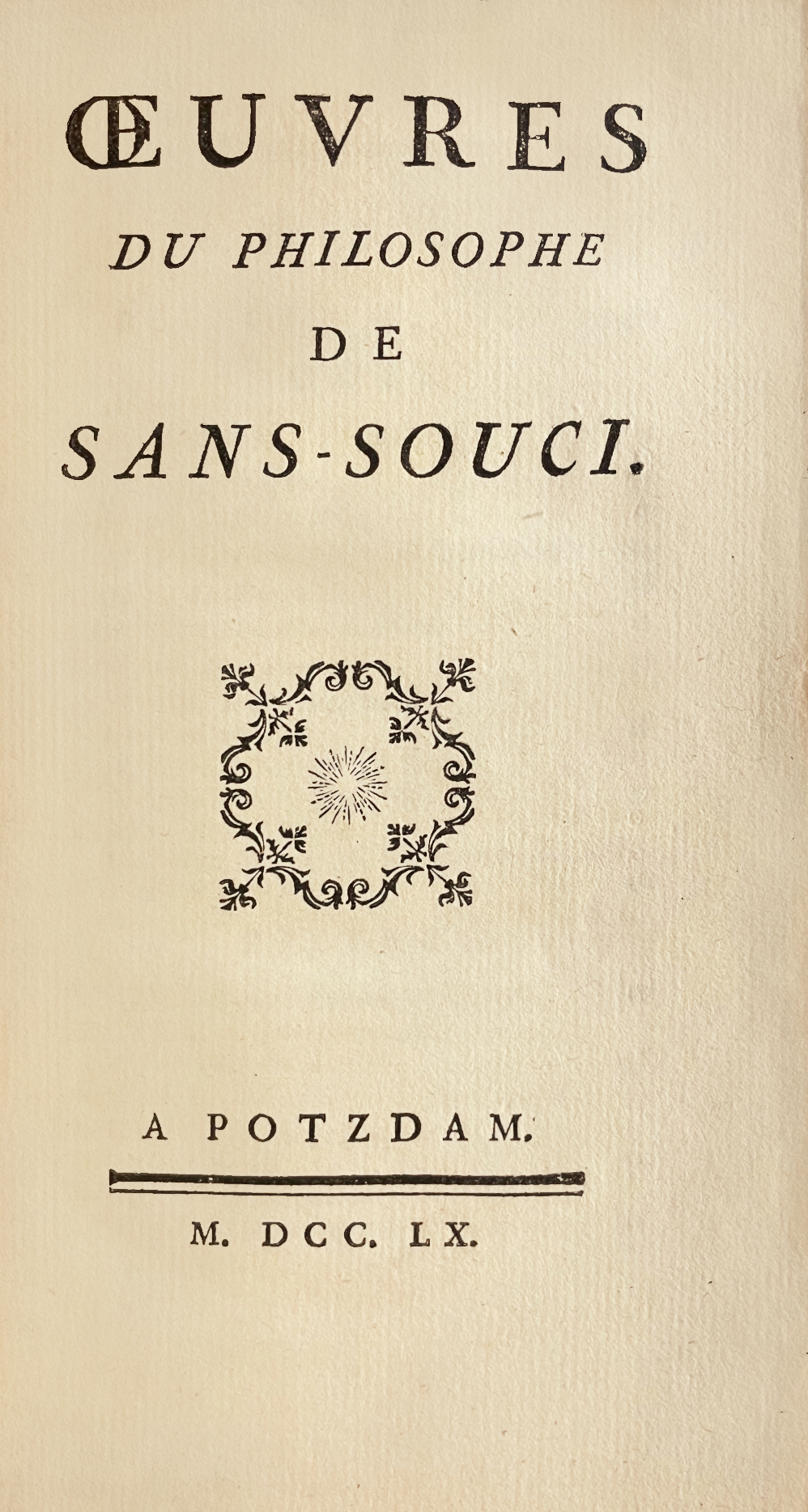

Potsdam, n.n., 1760.

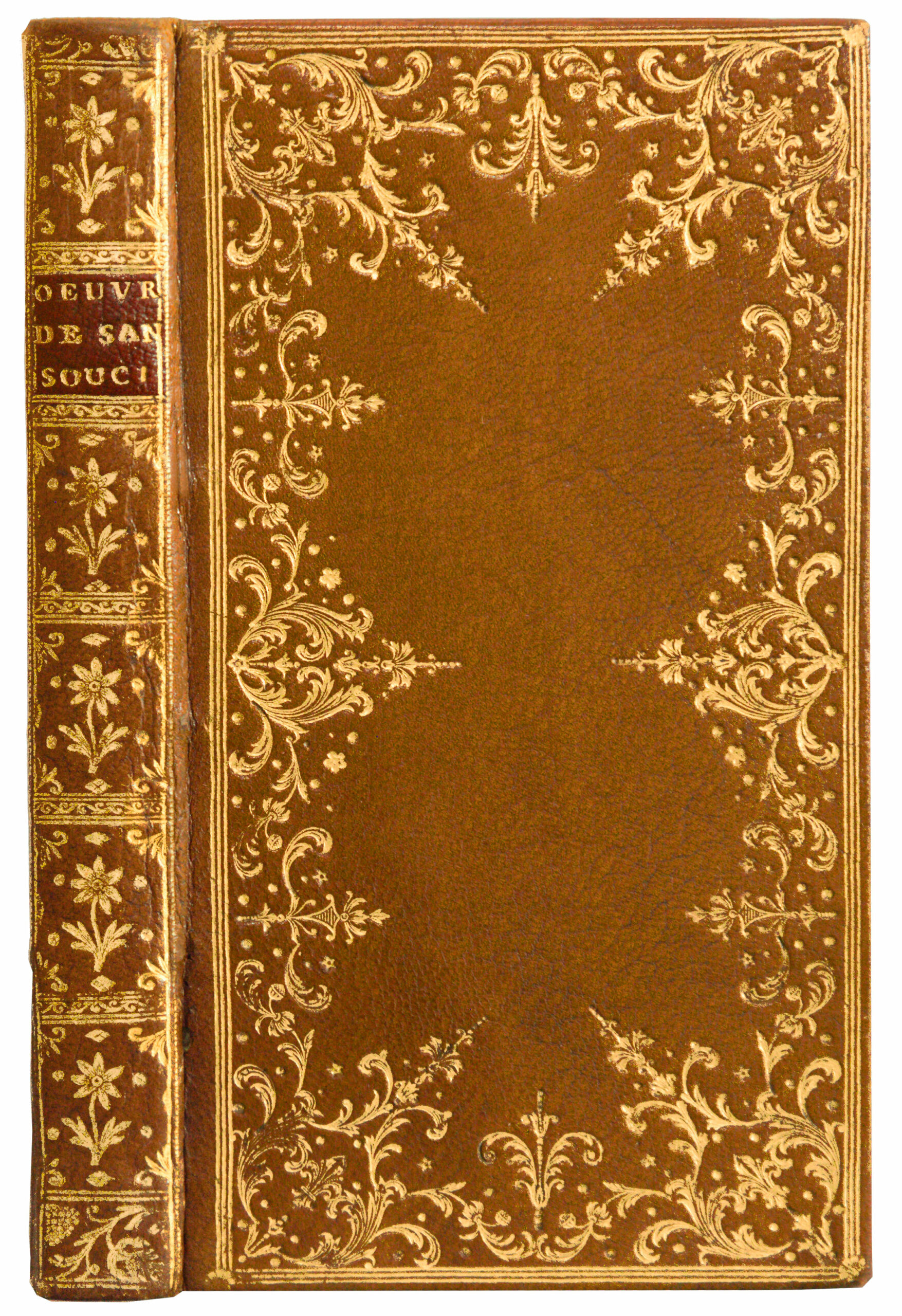

12mo [160 x 88 mm] of viii and 299 pages. Full citron morocco, triple gilt fillet around the covers, large fleur-de-lys dentelle around the covers, decorated flat spine, red morocco title-piece, inner border, paper endlêves and doublures with gilt stars and dots, gilt over marbled edges. Contemporary binding with fleur-de-lys.

Partly first edition of the Odes and Epistles of Frederick II, printed in Potsdam in 1760. The philosopher of Sans-souci refers to the Prussian king Frederick II the Grêt: he had the castle of Sans-souci built nêr Potsdam from 1745 on, after the second Silesian war. He died in this place, which he particularly liked, on August 17, 1786. The manuscript of the works contained in this edition, annotated in the margins by Voltaire who corrected it for the first edition, is preserved there. As soon as he accessed to the throne, Frederick took, according to a formula of Pierre Gaxotte, "twenty edicts to make a philosopher grow pale": he abolished torture, forbade bullying in the army, lightened the penalties for abortion, made the censorship of the press and printing more flexible, abolished the dêth penalty for thieves, abolished the obligation of ecclesiastical dispensations for marriages between distant relatives, and took an edict of tolerance on the free practice of all religions. Towards the end of his reign, he tried to abolish serfdom, but he came up against the landed aristocracy. In the eyes of the whole of Europe, he now embodied what was later called "enlightened despotism", an expression that neither Voltaire nor any philosopher used, since it was coined and sprêd by historians in the 19th century... The fine contemporary minds of Frederick II had a rêson to accept everything from the monarch: at the castle of Sans-Souci, they shared his intimacy. Voltaire had his room nêr that of the sovereign. The famous "round-table" of Sans-Souci saw long conversations taking place where the king showed himself to be a brilliant conversationalist. Voltaire evoked these evenings: “One had supper in a small room of which the most singular ornament was a painting whose drawing the king had given to Pesne, his painter. It was a bêutiful priapée. The mêls were not less philosophical. A visitor who would have listened to us, by seeing this painting would have believed to hêr the seven wise men of Greece in the brothel. Never in any place in the world were all the superstitions of men spoken of with such freedom, and never were they trêted with more jest and contempt.” It should be added that if the conversations were exclusively in French, the cooking was also of French inspiration since Frederick II had for a long time as his main master-cook the Frenchman André Noël (1726-1801) whose father was a pastry cook in Angouleme. Voltaire is the best known of these distinguished guests, but he was far from being the only one. Diderot, who was an admirer of Catherine II of Russia, the "Semiramis of the North", preferred to go to St. Petersburg, but he had a lot to say about the "philosopher king". The same flattering words can be found in the writings of Mirabêu, who happened to be in Berlin when Frederick II died in 1786. Frederick spoke better French than German. Frederick II a man of Culture and Letters: His interest for culture, arts and sciences, is obvious during all his reign. Frederick expressed himself mainly in French because at the time it was the language of access to culture. He tried to give much weight to his reputation of philosopher prince, and reconstituted the Academy of Berlin which became the Royal Academy of Sciences and Literature of which Maupertuis, a Frenchman, became the president. Frederick wrote many works, in 1740, the Anti-Machiavel and Considérations sur l’état présent du corps politique de l’Europe, in 1746, Histoire de mon temps. In 1748, at the end of the Silesian wars, he publishes the Principes généraux de la guerre in which he explains his maneuvers of envelopment, he studies and applies the military art more than any man of his time. In 1752 it was the turn of the Testament politique, in 1780, De la littérature allemande and finally in 1781 the Essai sur les formes de gouvernement et sur les devoirs des souverains. But it is in 1760 that he published his Odes and his Epistles. A precious and remarkable volume printed on fine Holland paper, the only one recorded from this edition preserved in its elegant contemporary royal binding in citron morocco with fleur-de-lys dentelle, with strong paper endlêves and doublures with gilt stars and dots. From the libraries of Henri Béraldi (June 1934, n° 90) and Comtesse de Behague.

See less information