N.p.n.d. [Paris, Imprimerie Royale, 1823].

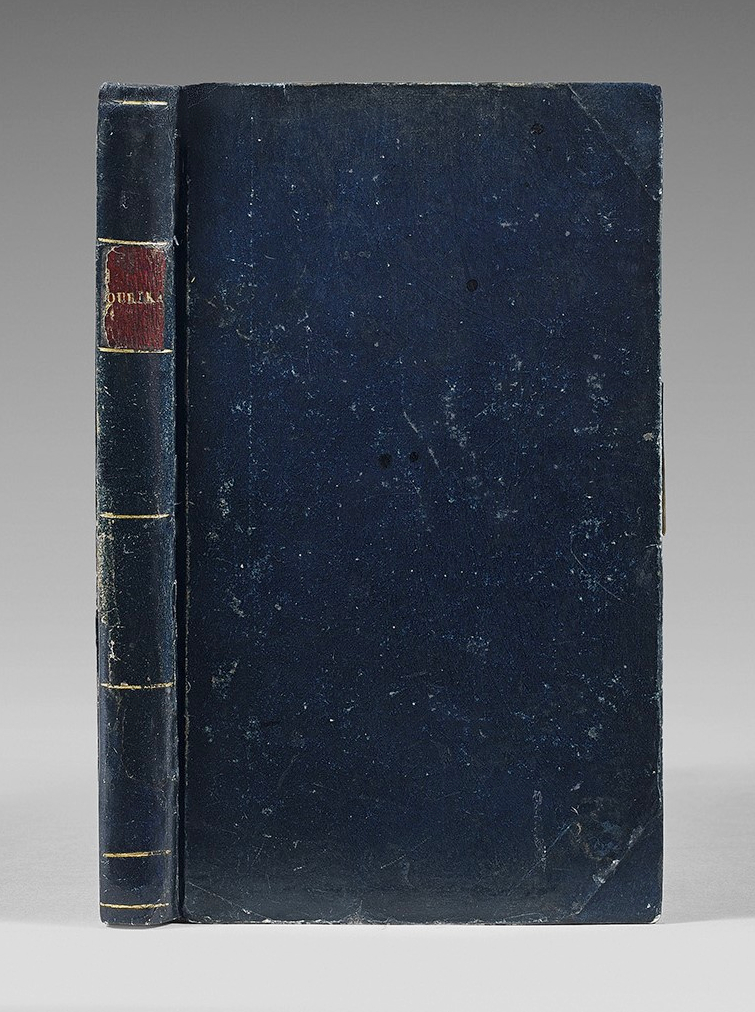

12mo of 108 pp. Midnight blue boards, spine in Bradel style, untrimmed. Rare boards of the time.

170 x 100 mm.

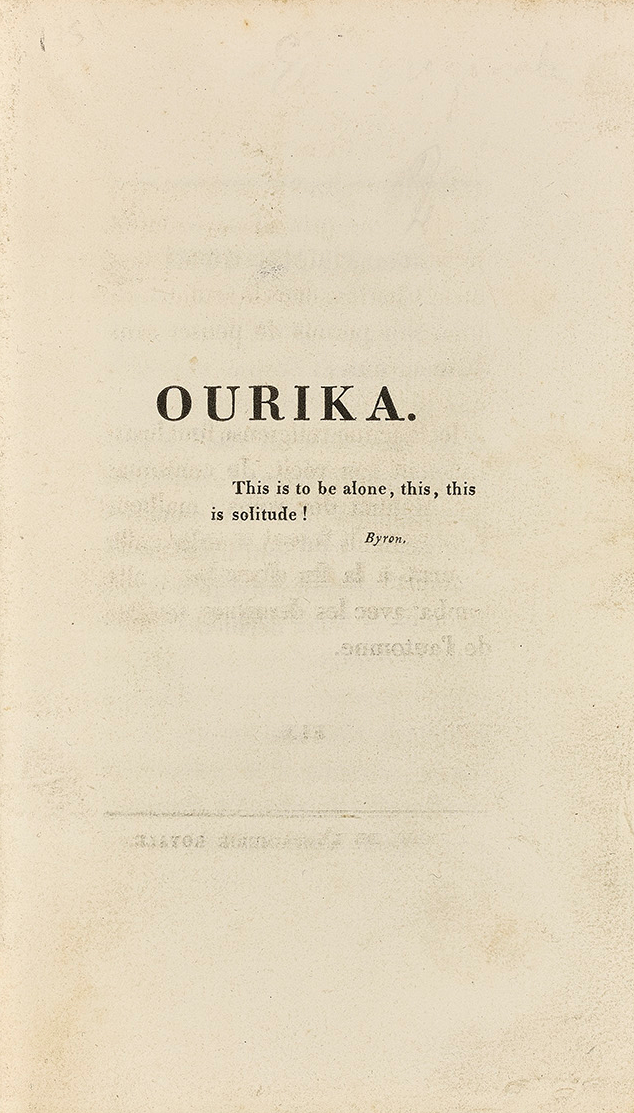

First edition first issue (with the mistake on page 88) “extremely rare” (M. Clouzot) and highly sought after.

Carteret, I, 250.

“Printed in a very small number (25 or 40 copies)” (Clouzot, 113). The standard print run of the time was several thousand copies. The copies were distributed by the duchess to her close ones.

“A bestseller under Louis XVIII“. [Lucien Scheler in Le Bulletin du bibliophile, Paris, 1988].

“The Duchess of Duras (1778-1828), daughter of a ship captain, Count de Kersaint, who died on the scaffold, emigrated with her mother to Martinique, then settled in London where she married the Duke of Duras, another émigré. She returned to France after the 18th Brumaire, but, during the entire Empire, lived secluded with her husband in their chateau in Touraine, where her only literary connection was her friendship with Chateaubriand, and especially with Madame de Staël. With the Restoration, the Duke of Duras was appointed Marshal of France and the Duchess returned to Paris, where she held a rather exclusive literary salon, where being admitted was almost a social consecration. She published this novel, which was very well received by the public.” (Dictionnaire des auteurs, II, 78).

“Under the Restoration, the salon of Madame de Duras was one of the most brilliant. ‘Soon,’ says Sainte-Beuve, ‘a small elite society formed in aristocratic boudoirs, a kind of Hôtel de Rambouillet worshipping art behind closed doors…’.”

Slavery being prohibited on French soil, a strange fashion spread in the second half of the 18th century: small Black children taken from Africa, who were virtually saved from colonial slavery, were offered here and there to wealthy aristocrats and bourgeois who made them the exotic delights of their homes or salons. Thus, a little girl taken from Senegal received an aristocratic education and ended her life as a nun in a Paris convent at the beginning of the 19th century. It is from her convent that the sick nun Ourika confides to her doctor the sorrow that has ravaged her life and brought her to the brink of the grave. Isn’t it always true that to heal us, doctors need to know the pains that destroy our health?

Ourika thus recounts her arrival in France at the age of two, her education and intellectual formation under Madame de B., who “personally oversaw her readings, guided her mind, shaped her judgment.” But at fifteen, she abruptly becomes aware of her color as the mark by which she will always be rejected, the mark that separates her from all beings of her kind, “which condemns her to be alone, always alone! never loved!” She thus becomes a stranger among her peers. In her sorrow, the gentle company of her mistress and her two sons is of no help to her.

“I was brought from Senegal at the age of two by Mr. Chevalier de B., who was governor there. He took pity on me one day when he saw slaves being embarked on a slave ship that was soon to leave port: my mother had died, and I was being taken onto the ship despite my cries. Mr. de B. bought me, and upon his arrival in France, he gave me to Mrs. Marshal de B., his aunt, the most charming person of her time…”

The charm of Ourika is that for the first time in European literature – as an English novelist has already noted – a white writer enters a Black consciousness with elegance and sincerity to the point of allowing white readers to identify with the character.

The publication of Ourika in 1824 provided the Duchess of Duras with one of the greatest successes of women’s novel. Instantly fashionable, this novella finely painted the story of a young Black slave girl in love with the son of her protectors.

Exceptional very pure copy, with wide margins (height 170 mm), of one of the rarest novels in 19th-century literature, preserved in its publisher’s binding, a condition of exception among the thirty or so copies printed about two centuries ago.