Basle, Frères Cramer, 1758.

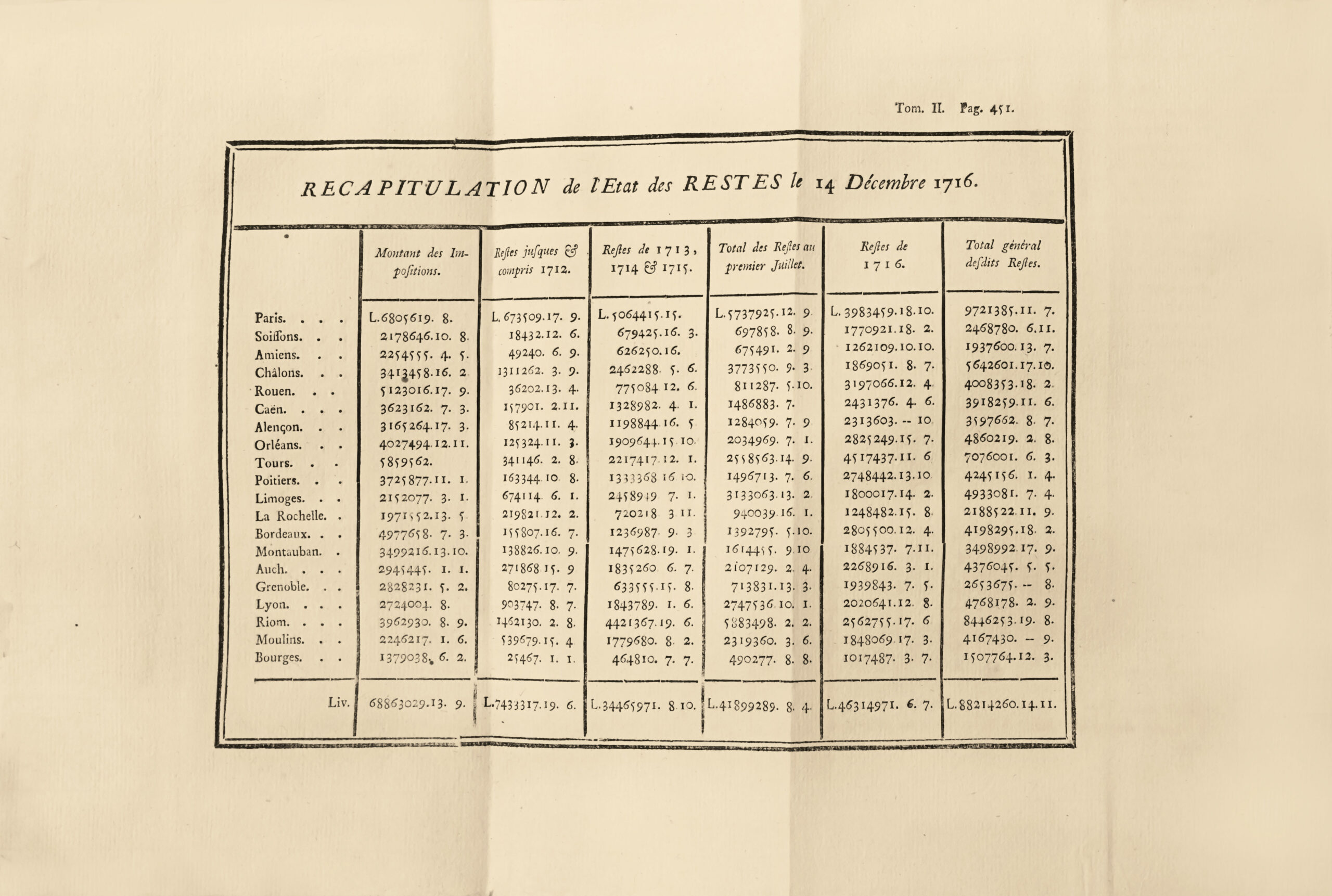

2 parts in 2 volumes 4to with : I/ (1) bl.l., viii pp., 594 pp., 3 folding tables; II/ (1) bl.l., viii pp., 662 pp., (1) bl.l., 13 folding tables.

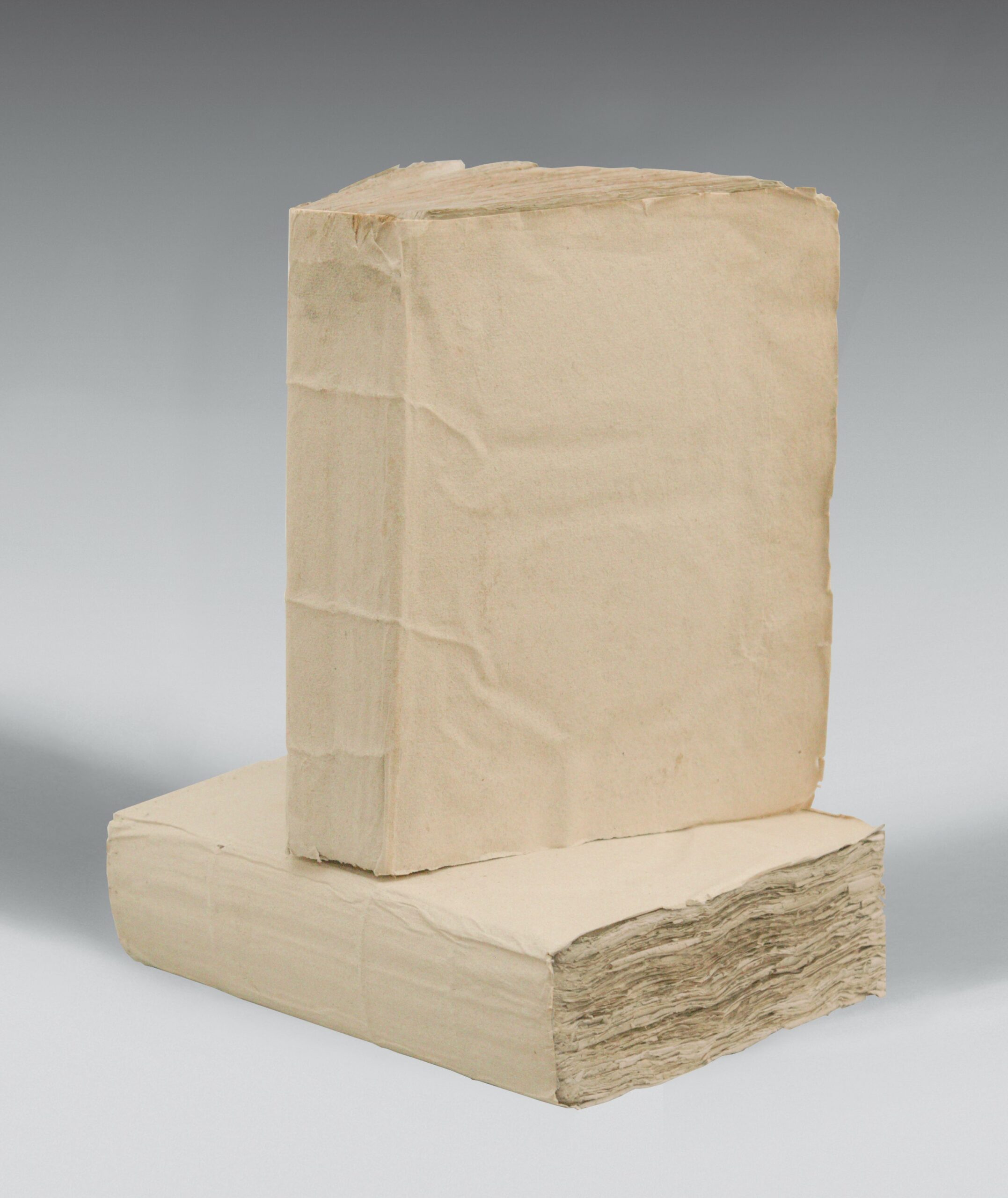

Preserved in wrappers as issued, untrimmed, second volume uncut. In slipcases.

275 x 210 mm.

First edition of Forbonnais’ great work on the finances of France.

Barbier, Anonymes, 19.

“Here ends Forbonnais’ great work, ‘Recherches et Considérations sur les finances de France’. It is not without regret that we part company with this guide, so learned, so sensible, so purely and simply patriotic, and without whom the financial history of the seventeenth century would have been almost impossible.” (H. Martin, Histoire de France, 1859).

“François-Louis Veron de Forbonnais, inspector general of the Mint and member of the Metz parliament, born in Le Mans in 1722, died in Paris on September 20, 1800.

Forbonnais was introduced to the world of commerce in his teens. His father, a stamen manufacturer in Le Mans with extensive contacts in southern Europe, sent his son, who was barely nineteen, to travel for his company in Italy and Spain. On his return, in 1743, Forbonnais moved to Nantes, to live with one of his uncles, a wealthy ship-owner from that city. There, he was able to see at close quarters the major export businesses, take notes on the habits and needs of the trade, and prepare himself through useful practice for economic work and the administration of finances.

It was in this direction that Forbonnais put his mind to work. In 1752, he presented the government with briefs on finance, plans and projects: admitted to discuss them before the minister, he supported his opinions with the stiffness of a man more accustomed to study than to the customs of the courts. Although the minister he had stood up to was honest, enlightened and full of the best intentions, Forbonnais was spurned. He did not, however, abandon his studies or his relations at court. The ministers, who at the time did not believe they knew everything, asked him for several memoirs. He became Inspector General of Coins in 1750, and in 1758 published the work that was to be his first title in the memory of posterity, his ‘Recherches et considérations sur les finances de la France’…

His great work on the finances of France, from 1595 to 1721, the result of long and conscientious research, outlives almost all the others. It shows an intelligence strong enough to dominate such a subject, without getting lost in the details. A style that is clear, simple, precise and grave throws interest and light on facts that are dry and obscure in themselves.

The ‘Recherches et considérations sur les finances’ can be consulted with complete confidence for the length of time covered by the author’s plan; digressions on the origin and ancient history of certain taxes should be distrusted. Some modern writers, who owe Forbonnais a good part of their reputation, have not always corrected the mistakes this author made.

As a publicist, Forbonnais is positioned, by the nature of his ideas and the time in which he lived, between law and Quesnay’s school. He took part in the reaction against the fashions, ideas and examples of England and Holland, and looked to the French tradition for thoughts of improvement and reform. ‘This work, he says in his introduction, will preserve for our nation the honor of having been the first to have good laws in all things, and perhaps the shame of having executed them badly’. The most accurate and true economic ideas abound in his writings, but they don’t yet have an exact, scientific form. “. (C. Coquelin, Dictionnaire de l’économie politique, 1864).

The work is adorned with 16 highly interesting folding tables showing, for example, the state of expenditure in 1670, actual expenditure in 1682, etc.

A precious copy preserved in wrappers as issued, untrimmed.