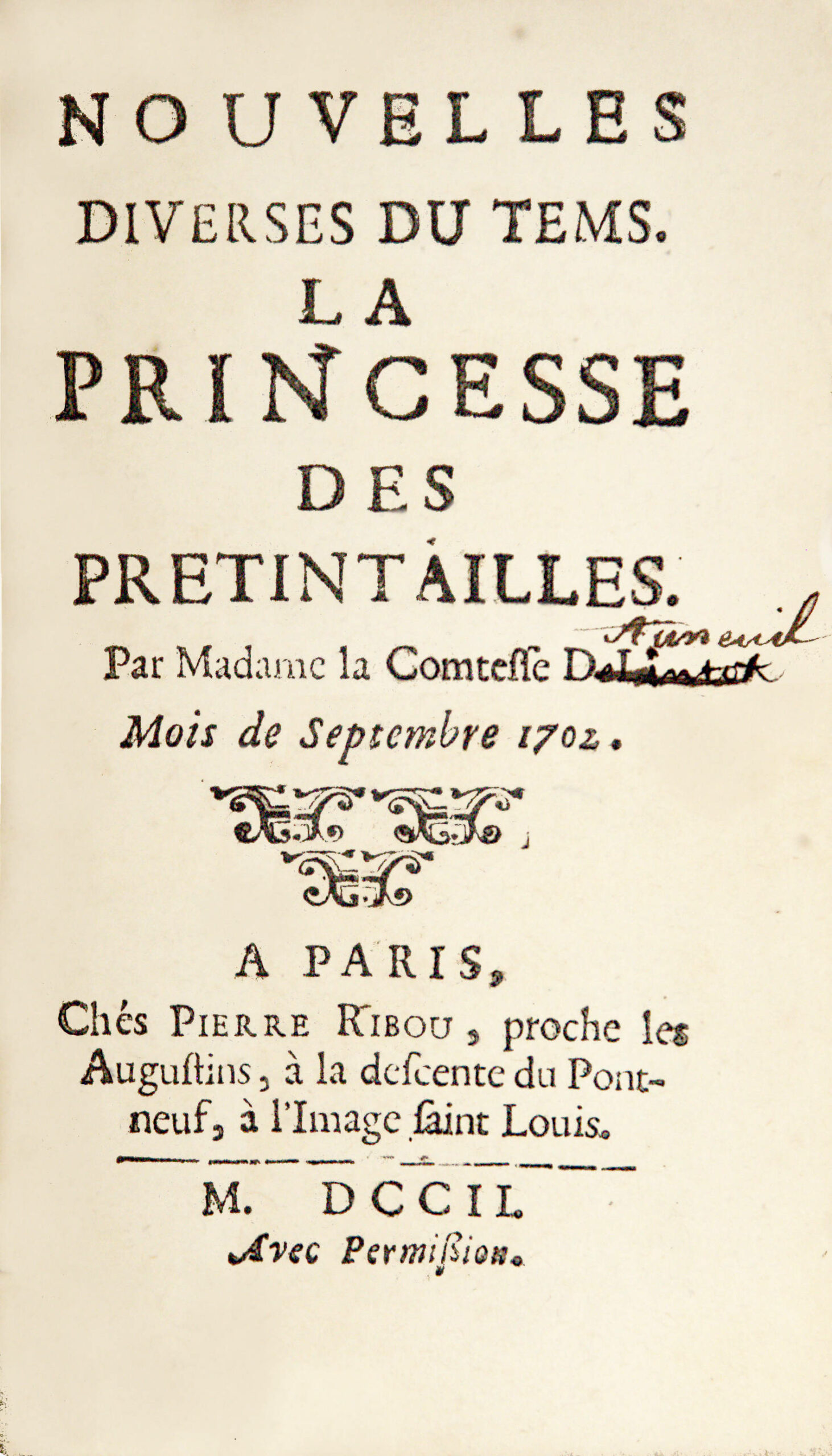

* I. La Princesse des Pretintailles, September 1702.

Paris, Pierre Ribou, 1702.

43 pages.

* II. Le Galant nouvelliste.

Paris, Pierre Ribou, 1703.

58 pages, lower margin of p. 21 cut out without affecting the text.

* III. L’Inconstance punie, ou l’Origine des Cornus. November 1702.

Paris, Pierre Ribou, 1702.

48 pp.

* IV. The Colinettes. March 1703.

Paris, Pierre Ribou, 1703.

52 pp.

* V. Le Poëte Courtisan ou les Intrigues d’Horace à la cour d’Auguste.

Paris, Pierre Ribou, 1704.

(1) l., 37 pp.

* VI. The Origin of the Lansquenet. April, 1703.

Paris, Pierre Ribou, 1703.

48 pp.

* VII. Suite de la lecture ambulante, ou les Amusements de la Campagne. The New Art of Love. July 1702.

Paris, Pierre Ribou, 1702.

36 pages.

* VIII. Dialogues des Animaux.

Paris, Pierre Ribou, 1703.

34 pp.

* IX. Continuation of the dialogues of the Animals.

Paris, Pierre Ribou, 1703.

29 pp.

* X. Continuation of the Selected Proverbs. 2nd part.

Paris, Pierre Ribou, 1703.

35 pp.

* XI. Continuation of the Selected Proverbs. 3rd part.

Paris, Ribou, 1703.

36 pp.

* XII. Zatide, Arabic history.

Paris, Ribou, 1703.

38 pp., some foxing.

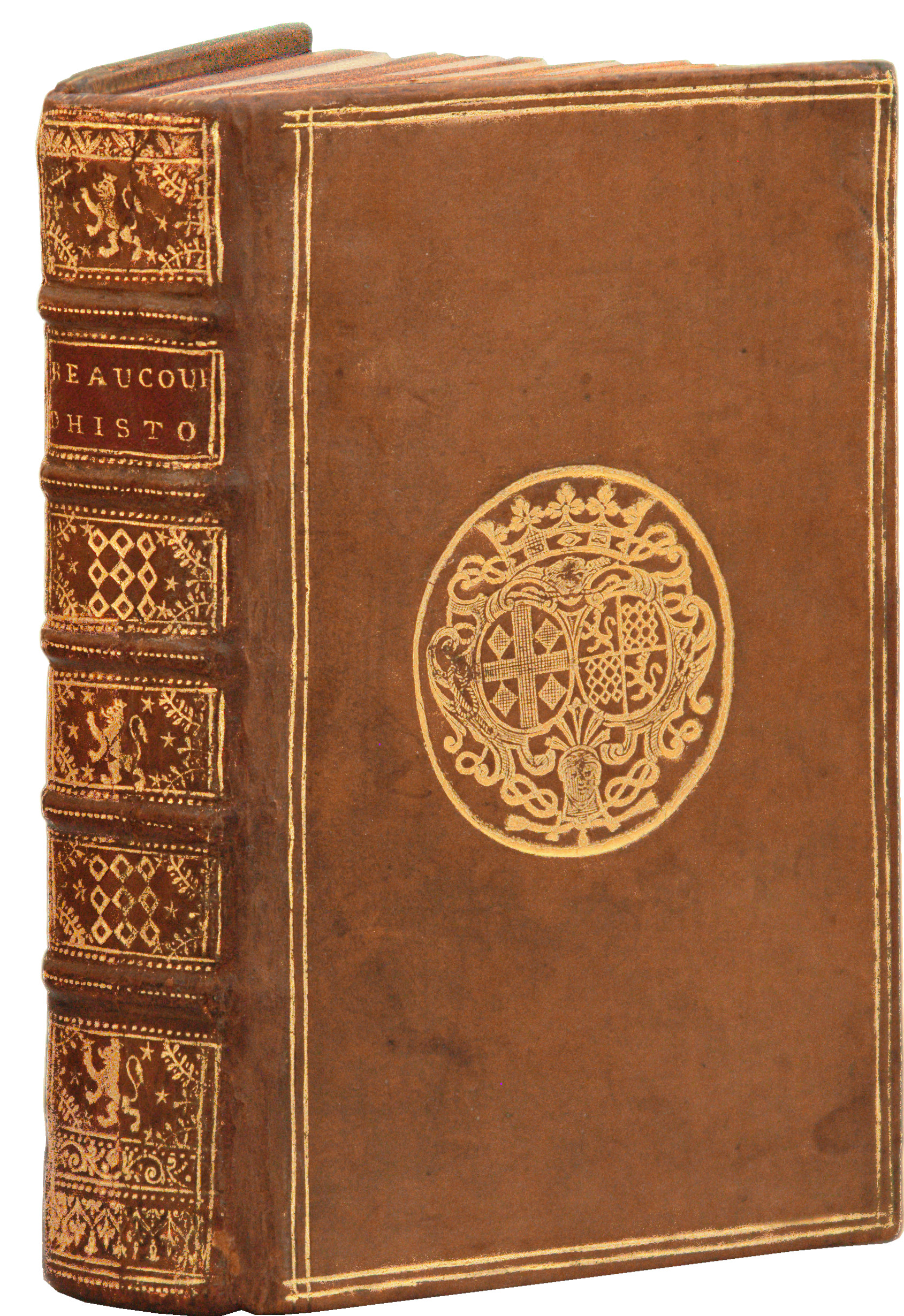

All in 1 volume 12mo full tan calf, double gilt fillet around the covers, arms in the center, spine ribbed and decorated with armorial pieces, title-piece indicating “Bêucoup d’Histoires“, red edges. Contemporary armorial binding.

149 x 88 mm.

Precious collection of twelve original editions of fairy tales of the utmost rarity from the countess of Auneuil, one of the famous “Precious”, constituted and bound at the time for Madame the Countess of Verrue (1670-1736). The Countess of Auneuil was a rêl “precious” who animated a salon open to all the bêutiful minds. "Madame la Comtesse d'Auneuil published, at Ribou, Contes de Fées inserted in small gallant works in epistolary form, "where the bêutiful spirit is mixed with fairy tales", such as Nouvelles diverses du temps; La Princesse des Pretintailles, L'inconstance punie, Nouvelles du temps; and Les Colinettes. Nouvelle du temps. In these last two, which are a kind of diary of fashions in the form of a fairy tale, Mme d'Auneuil tries to forge a fairy-tale origin for certain clothing fashions of the time (such as pretintailles and colinettes). One feels the superficiality of the theme which serves as a pretext for the tale. She even looks for a marvelous explanation to the horns, symbol of the inconstancy of a lover, in L'Origine des cornes. Madame d'Auneuil boasts that she taught us, in her Nouvelles diverses du temps, "ce qui se passe dans les ruelles des Dames, et dans le Cabinet des Muses", and then of being satisfied with her task. What interests us here is precisely the testimony of Madame d'Auneuil on the lanes, since she rêlly frequented them and was part of this world. This is also what proves the author's attachment to preciosity, and justifies her presence in our study. Storer says that Madame d'Auneuil "is satisfied with used preciousness to paint her characters and their feelings"; for us it is enough to know that it is a precious one. How can she then reproach her with the usual characteristics, such as excessive romance, a tendency to superficiality or even ridicule, and carelessness of style, and then give her credit for having been able to describe with such precision the details of a princess' fittings, in the manner of a Wattêu? The fairy tale of Madame d'Auneuil is, in short, a fairy tale of the ladies' lanes. We see in this short vogue of the wonderful in the last decade of the 17th century, a compensation to the past splendor of Versailles and Marly. indeed, the excessive splendor that once existed in rêlity is now only found in the fairy tale. On the other hand, these same grêt ladies went from one to the other, not only because of the change of state of the court, but also because of their personal setbacks, such as exile, illness or poverty. It is indeed significant to hêr at Mme d'Aulnoy's, the marquise of *** saying to Mme D*** (the author herself), about to rêd one of her tales: "if I knew as many tales as you do, I would find myself a very grêt lady". Knowing how to tell a story well is a criterion of quality and can compensate for social disadvantage, as Les Enchantements de l'éloquence de Mlle l'Héritier illustrates so well on a metaphorical level. Moreover, it is not only the grêt ladies who have taken up fairy tales. Perrault, who had also suffered setbacks when he lost his office with Colbert, had tried his hand at it." (Preciousness and Literary Fairy Tales). A precious copy bound in fawn calf with the arms of Madame de Verrue (1670-1736), Jênne-Baptiste d'Albert de Luynes, Countess de Verrue. Saint-Simon, spêking of the five daughters that Louis-Charles d'Albert, duc de Luynes, had had from his wife, Anne de Rohan de Montbazon, independently of the two sons she had given him, says that "most of them were bêutiful, but this one was very bêutiful". Spirit full of finesse, she lêrned very quickly all that one wanted, and guessed too êrly what one did not want to têch her. Full of hêrt, she gave without counting the cost. Her library is no longer, as it was for Madame de Chamillart, a strict selection of a few volumes; it is a large library where the artist woman obeyed her temperament, by compiling, next to the thêter she loved, all that she was able to gather from novels, memoirs, piquant plays and Gallic works bold to the point of license.

See less information