Paris, Hippolyte Souverain, 1842.

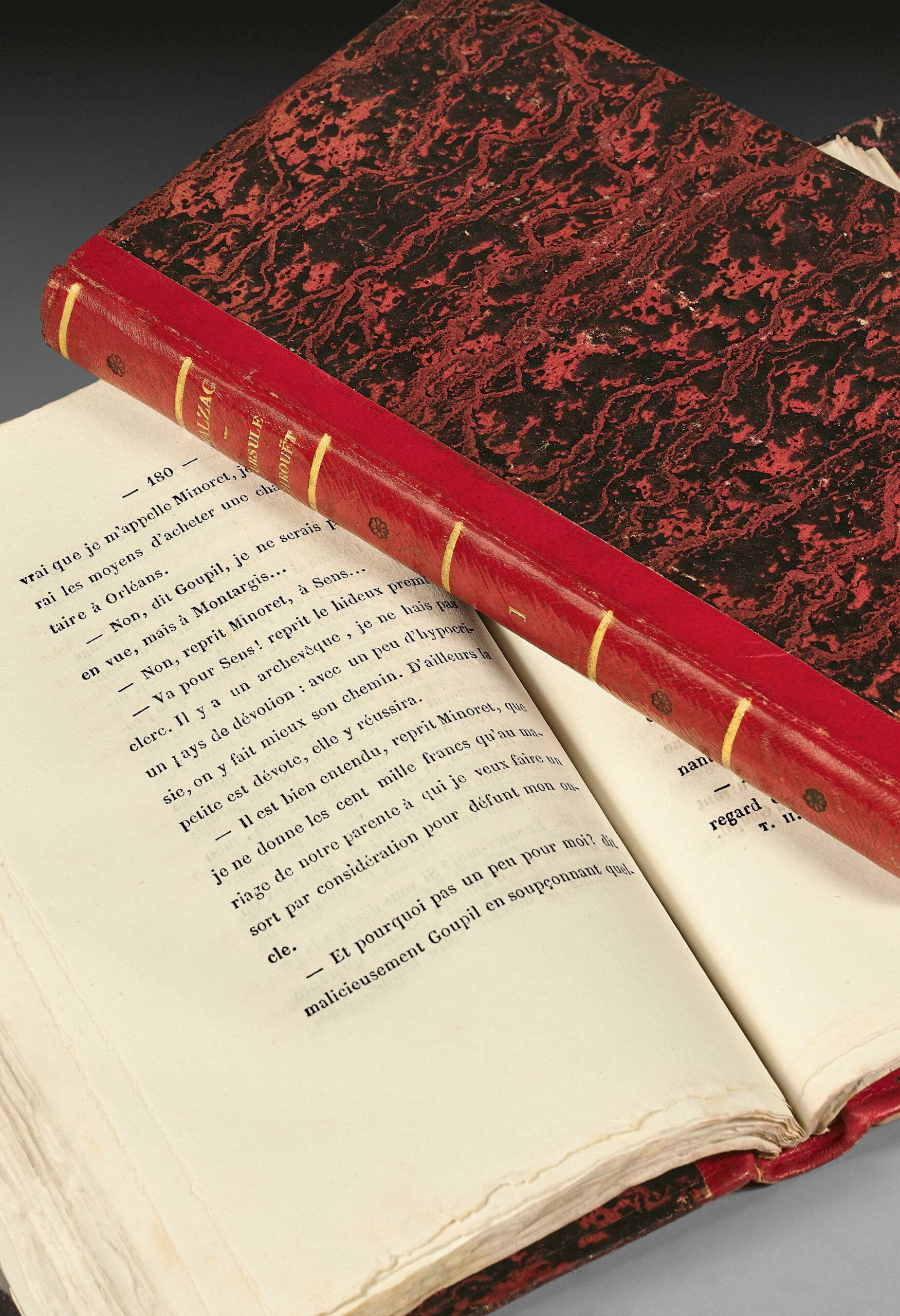

2 volumes 8vo of 327 pp., 336 pp. Red half-sheepskin, smooth spines decorated with gilt fillets and black floral ornaments/ fleurons, entirely untrimmed. Contemporary binding.

225 x 137 mm

Original rare edition (Clouzot 30).

It was missing from the romantic collection of Maurice Escoffier.

Vicaire, I, 217; Rahir, La Bibliothèque de l’amateur, 306; Catalogue Destailleur 1379.

One of Balzac’s key works, steeped in occultism.

Balzac described the story of Ursule, “the happy sister of Eugénie Grandet”, as “privileged”.

The novel opens the Scènes de la vie de province (Scenes of provincial life): a young girl manages to triumph over the machination hatched against her to rob her.

This portrait of a young girl was dedicated by Balzac to his niece, Sophie Surville.

The first part of Ursule Mirouet, “Les Héritiers alarmés”, introduces us to the good society of Nemours, or rather to the four related bourgeois families that dominated the small town under the Restoration. Minoret-Levrault, the postmaster, is a kind of stupid Hercules, dominated by his wife, the worrying Zélie; the couple lives for their son, Désiré, a young dandy who is studying law. Doctor Minoret, a former disciple of the Encyclopedists and a convinced atheist, has returned to his home town, where he is finishing his brilliant career as the Emperor’s doctor in retirement. The doctor has no children, and his nephews, including the postmaster, think they will share his inheritance. But Minoret brings into his house an orphan, Ursule Mirouet, daughter of a singer, himself the natural child of an organist. Ursula was his niece and he brought her up as his daughter, directing her education himself with the help of his old friends, the priest Chaperon, the justice of the peace Bongrand and the old officer Jordy. As she grew up, little Ursula realised that her uncle and godfather did not share her faith, and she felt great pain. The old doctor, who had been estranged for a long time from an old friend who had taken up the study of magnetism, suddenly received news of her. His friend asks him to see him again in Paris. Minoret goes to the appointment and attends a session of magnetic experiments during which a clairvoyant explains to him, point by point, the small gestures of his goddaughter who has remained in Nemours. Back in his house, the doctor finds that the clairvoyant’s words were scrupulously accurate. Shaken in his convictions, moved by the suffering caused to Ursula, now a young girl, by her impiety, the old atheist suddenly converted. This unforeseen event causes confusion among the heirs: is Minoret not going to leave his property to the Church, or even worse, make his goddaughter an heir? So the old man is surrounded by maneuvering and suspicion. But the doctor is much more troubled by a discovery he has just made; Ursule is in love with a young neighbour, Savinien de Portenduère. Shortly afterwards, the young man is put in prison for debts; his mother, a widow and poor, can do nothing for him, and it is Doctor Minoret who advances the money necessary for his release; he himself goes to rescue him from prison. It is Savinien’s turn to fall in love with the beautiful Ursula. The indulgent doctor Minoret is ready to give his consent to this union, if Savinien redeems his past behaviour; but the proud Mme de Portenduère remains intractable, her son will not marry an orphan, daughter of a “captain of music”, himself a natural son. So Savinien leaves Ursule to join the navy during the conquest of Algeria. He returned from the navy as a glorious officer, but his mother did not want to give in. Faced with this attitude, the doctor is forced to close his door to Savinien.

This first part is only the prelude to the drama that opens with the doctor’s death (Part II, “The Minoret Estate”). The old man’s arrangements had been made, he had concealed bearer bonds for his goddaughter, leaving his legal heirs their normal share of the inheritance. On his deathbed, the doctor gave Ursula the key to the cabinet where the money he had intended for her was hidden; but the young girl, confused, let herself be distanced by one of the heirs, the postmaster Minoret-Levrault, who, hidden near the death chamber, had heard everything. Minoret-Levrault takes the loot and everyone is surprised that Ursule has only received an insignificant sum. The young girl, who is persecuted by the heirs, retires to a small house with a servant; all hope of marrying Savinien de Portenduère is now lost to her. But the presence of Ursula in the town bothers Minoret-Levrault, who has not confessed his theft to anyone, not even to his wife. He asks the despicable Goupil, a satanic and repulsive notary clerk, to help him chase the girl away. Goupil then begins a campaign of anonymous letters that terrorises the poor girl and brings her very close to death. But as Minoret-Levrault, who has built up a huge fortune, does not pay enough for the services rendered by Goupil, he decides to take revenge. He confesses to being the author of the plot, but he was only an instrument in the hands of Minoret-Levrault. The doctor’s old friends, who continue to protect Ursule and Savinien, who has remained faithful, wonder why Minoret-Levrault would want Ursule to leave at all costs. Ursula sees her uncle again in a dream, and the dead man reveals to her all the details of Minoret-Levrault’s infamy. From presumption to presumption, the theft is discovered. Minoret-Levrault’s eldest son dies in an accident which the deceased had told his goddaughter about; his wife goes mad, and he, hard hit, becomes a pallid and devout old man who tries to redeem his deed.

Ursula finally marries Savinien and they live in the castle acquired by the postmaster, which he has abandoned to them.

It is hardly necessary to emphasize the naivety of the plot, in which magnetism, super-terrestrial manifestations and apparitions play a very large part. Here Balzac indulges his deep-seated convictions about the reality of occult phenomena. In this strange and poignant melodrama, innocence is persecuted, but it will receive the reward it deserves, and the wicked will be punished. But Ursule Mirouët is also a very moving account of the relationship between an old man and a young girl, an evocation full of delicacy, inspired by a deliberately optimistic knowledge of the human heart, and, in contrast, a pitiless analysis of provincial mores and dishonesty, which sometimes goes as far as crime, and to which middle-class people who aspire to an inheritance and believe they have rights over it can be drawn. Rarely has Balzac gone so far in his rigor and hatred for the provincial bourgeoisie and the unhealthy seeds it generates, sustains and develops.

Very fine copy bound by Wagner, entirely uncut, for Balzac himself.

In an article published in the Courrier Balzacien, Thierry Bodin underlines how “personal copies of Balzac are very rare. Most of them were dispersed at the sales before and after the death of Madame de Balzac [Madame Hanska] in March and April 1882”.

The bindings were all executed either by Spachmann or by Wagner, or by both craftsmen when they worked together, according to the writer’s instructions. “They are also more or less uniform: smooth red basane spine (decorated with a few gilt fillets and cold fleurons) with rather flexible seams that allow the book to be opened easily, the latter untrimmed, with full margins, and largely protected by larger boards covered with marbled paper, the endpapers always being of white paper on which it would be possible to write” (Thierry Bodin).

Provenance: Honoré de Balzac – Madame Hanska, widow of Honoré de Balzac, in whose sale about 2,500 volumes were offered as lots (Paris, 25 April 1882); Auguste Lambiotte (Cat. I, 1976, no. 48, reprod. pl. XII); Pierre Bergé, 14 December 2018, no. 904 (estimated € 38,000 – 50,500 incl. fees).