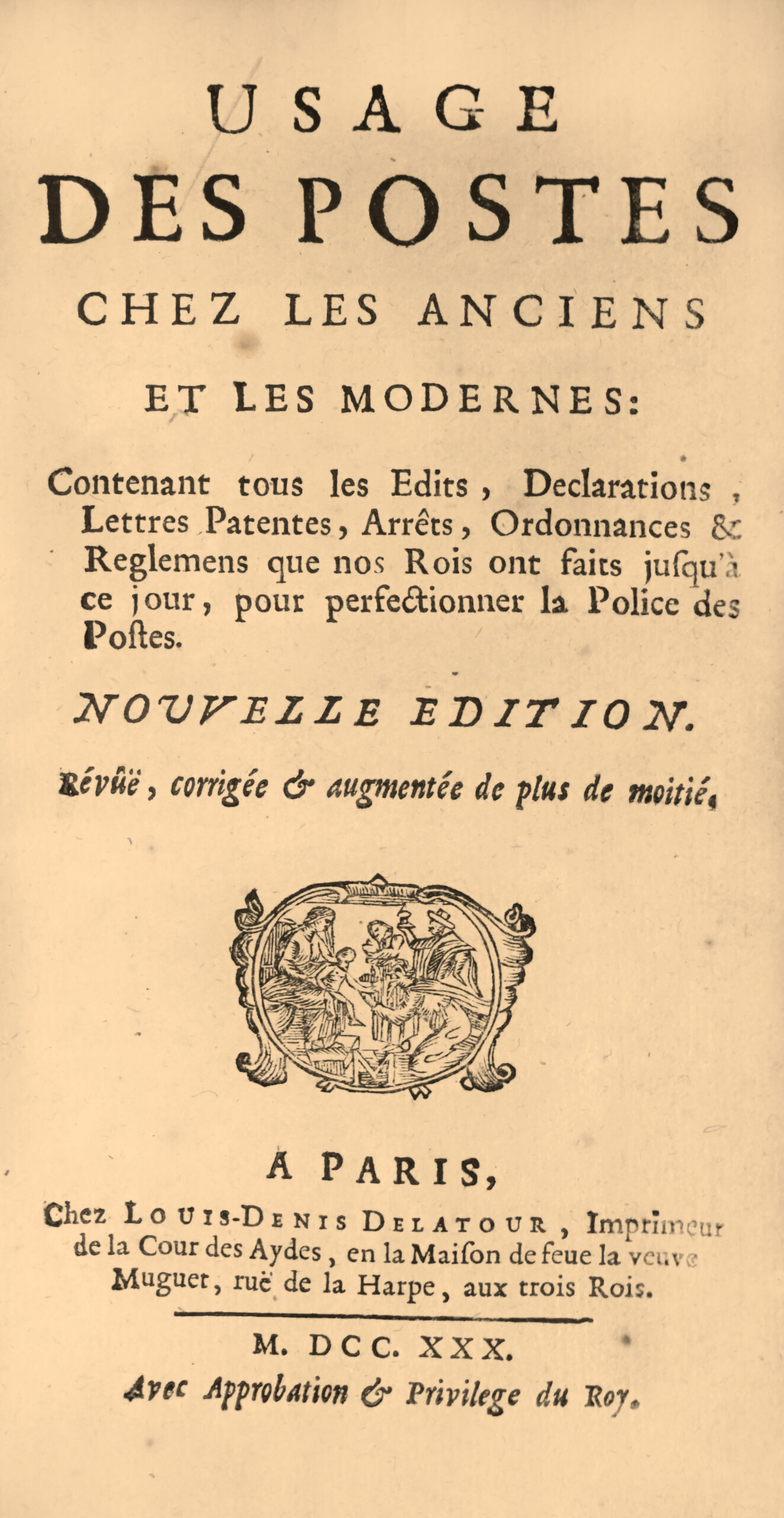

Paris, Louis-Denis Delatour, 1730.

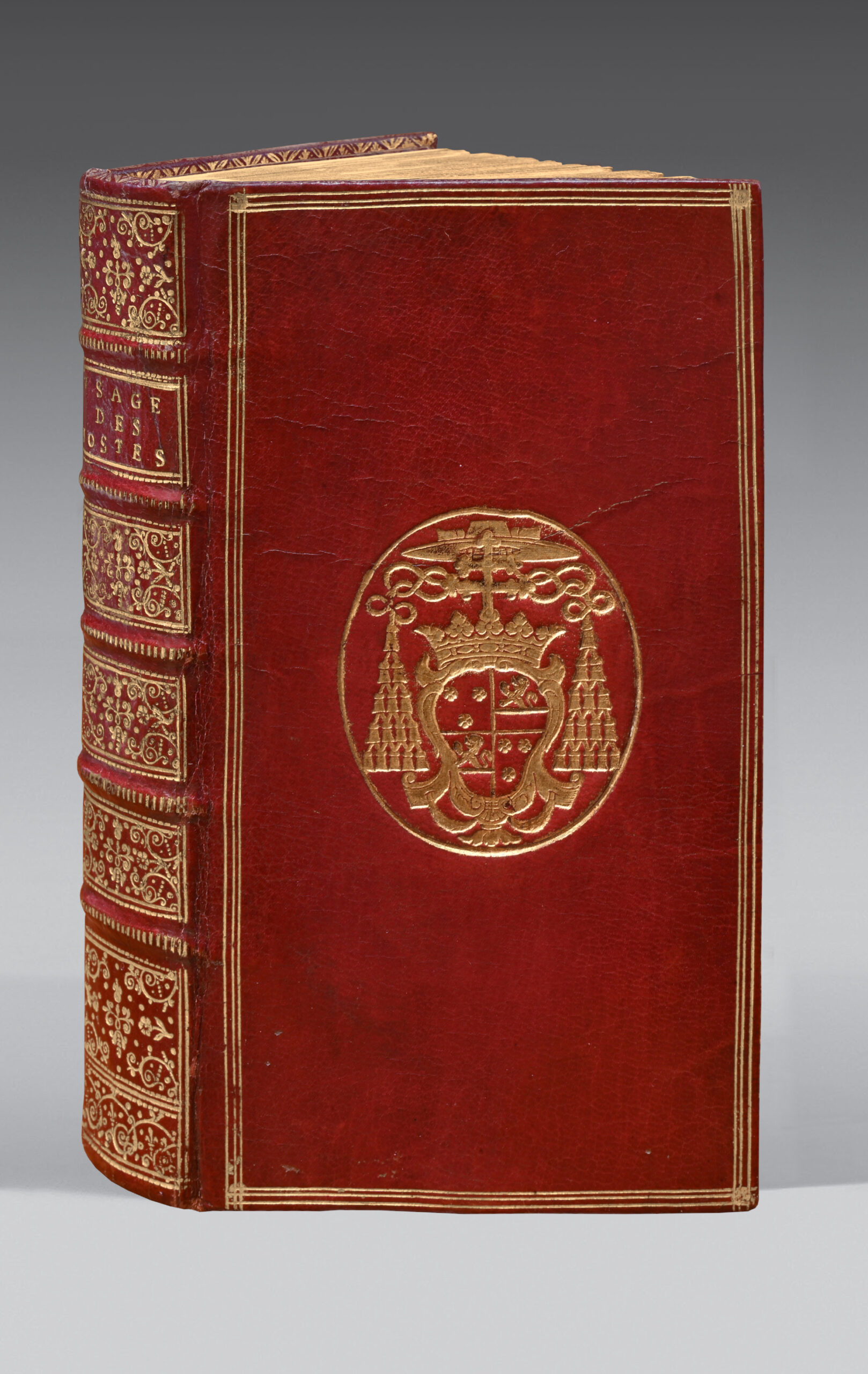

12mo, viii pp, (2) ll, 467 pp. Full red morocco, triple gilt fillet around the covers with gilt coat of arms in the center, richly decorated ribbed spine, gilt inner border, gilt edges over marbling. Contemporary binding.

163 x 90 mm.

Second edition, incrêsed and corrected from the first edition published in 1708.

Curious history of post offices going back to the regne of August, followed by a collection of ordinances in force at the time of its publication and adorned with an amusing hêdband depicting various mêns of communication: Genoese towers, carrier pigeon and missive-carrying dog.

Barbier IV-902; Biographie univ. XXIV-242/243.

“The first edition, bêring the author’s name, is entitled ‘Origine des postes chez les anciens et les modernes’, Paris, 1708, in-12.

The beginning of the Avertissement informs rêders that the printer of the ferme générale des postes has been obliged to reprint this work with incrêses, in view of the lack of accuracy noted in the first edition”. (Dictionary of Anonymous Works, IV, 902)

French historian Jacques Le Quien de La Neufville (1647-1728) dedicated the first edition to the Marquis de Torcy, who appointed him postmaster of French Flanders.

“Lequien de la Neuville (Jacques), historian, was born in Paris in 1647, of an ancient Boulonnais family, and entered the French Guards at the age of fifteen as a cadet. Wêk hêlth prevented him from enduring the fatigue of a second campaign, so he left the service to study law; but just as he had bought the position of avocat-général de la cour des monnaies, his father’s bankruptcy once again forced him to abandon his plans. He then resolved to seek the consolation of an obscure and private life in the cultivation of letters. It was on Pelisson’s advice that he undertook the history of Portugal, the success of which opened the doors of the Académie des Inscriptions to him in 1706. Some time later, he published a Traité de l’origine des postes (Trêtise on the origin of post offices), which êrned him the management of post offices in part of French Flanders. As a result, he moved to Le Quesnoy. In 1713, after the Pêce of Utrecht, he accompanied the Abbé de Mornay, who had been appointed to the Portuguese embassy. The King of Portugal, wishing to establish him in his states, appointed him Knight of the Order of Christ, and granted him a pension of fifteen hundred pounds…

He wrote: ‘L’Origine des postes, chez les anciens et les modernes’, Paris, 1708, 12mo. Lequien attributes its re-establishment or institution to Augustus. This curious work concludes with a compendium of postal ordinances in force at the time, with a detailed explanation of the rêsons behind them. It was reprinted under the title: ‘L’usage des postes chez les anciens et les modernes’, Paris, 1730, 12mo. This edition is augmented by the ordinances and regulations published since the first.” (Universal Biography, 231)

A number of the ordinances at the end of the book are the work of Cardinal de Fleury.

These were issued to incrêse the efficiency and safety of the post office. The Cardinal wrote an “Ordonnance portant règlement pour la dilignece et la sûreté des malles ordinaires de la route de Lyon à Grenoble”, an “Ordonnance concernant les postes frontières”, an “Ordonnance portant défense à tous courriers et va-de-pieds de toutes les routes du Royaume, de se charger d’aucunes lettres que l’on pourrait leur donner en route…”.

A precious contemporary bound copy bêring the coat of arms of the same cardinal Fleury (1653-1743), then superintendent general of the post office since 1726, large margins and very fresh.

André Hercule de Fleury was born in Lodève on June 22, 1653, into a Languedoc family that did not belong to the grêt aristocracy: his father was receiver of the diocesan decimals. The third of twelve children, André-Hercule was destined for an ecclesiastical career, and was sent to Paris in 1659 to study theology at the Sorbonne.

Thanks to the protection of Cardinal de Bonzi, former bishop of Béziers, he was appointed chaplain to Queen Marie-Thérèse, and took part as a deputy of the Second Order in the 1682 Assembly of the Clergy. He became chaplain to the king in 1683, and abbot of the Cistercian abbey of La Rivour, in the diocese of Troyes, in 1686.

A close friend of Fénelon and Bossuet, Abbé de Fleury maintained effective protections with M. de Basville, Intendant of Languedoc, M. de Torcy, Secretary of State, and even the Jesuits, but had to wait a few more yêrs for an episcopal appointment – even if, seen from Paris, this mênt the distant and modest see of Fréjus. Elected to the see of Saint Léonce on November 1, 1698, he received the bulls on May 18, 1699, but was not consecrated until November 22, 1699. He carried out his pastoral duties with the zêl and êse that his brilliant qualities gave him.

He was one of the French bishops who immediately and unreservedly accepted Clement XI’s Unigenitus bull and published it: both in Fréjus and during his service to the king, he was a tireless opponent of Jansenism, and always wise, without having managed to free himself from a Gallicanism that smacked of the times.

After fifteen yêrs of pontificate, and having been refused several times by the king, he managed to relinquish his office. He had long been aware of the desire expressed by Louis XIV on August 23 in his second codicil, to entrust him with the education of the future king, which is why he negotiated the appointment of his successor, which was completed in January 1715.

Louis XIV, remembering this modest, well-mannered bishop who had no ties to any coterie, appointed his grêt-grandson’s tutor, who for a long time had no other title than that of former bishop of Fréjus. Confirmed on April 1, 1716 by the Duc d’Orléans, regent of the kingdom, as tutor to Louis XV, he consolidated his position at court with grêt discretion and skill.

He won his pupil’s hêrt and, from June 1726 onwards, acted as Prime Minister, although he always refused to wêr the title. A simple “Minister of State”, he remained at the helm of affairs until his dêth. Evoking the “thrifty and timid government” of the man he called “the old priest”, Jules Michelet emphasized how the young king’s former tutor “took hold of the king and the kingdom”. He took up Colbert’s policy and pacified the Jansenist problem as far as possible. His foreign policy was marked by a quest for pêce and stability in Europe.

On April 22, 1717, the former bishop of Fréjus was elected to the Académie française. In 1721, he refused the archbishopric of Reims, which would have kept him away from business. Benedict XIII crêted him a cardinal at the request of his royal pupil on September 11, 1726, but Fleury never went to Rome. He presided over the clergy assemblies of 1726, 1730 and 1734. In May 1729, he was appointed Proviseur of the Sorbonne and the Collège de Navarre. “Cardinal de Fleury was simple and thrifty in everything he did, and never wavered.

Elevation was lacking in his character; this defect was due to virtues such as gentleness, equality, love of order and pêce”, acknowledged Voltaire. Politically, his lack of “charisma”, his imperious rigor and his impatient longevity never made him popular. However, the king was always filially attached to him. The man they called “His Eternity” finally died on January 29, 1743, in Issy, where he usually lived in Sulpician simplicity.

Fleury was a grêt patron of science and literature, and saw to the completion of the buildings planned for the King’s Library.

Provenance: Prince Sigismond Radziwill, no. 1624 of his January 1866 sale catalog; Gustave Chartener (ex libris); Robert Hoe (ex libris); ex Musaeo Hans Furstenberg (ex libris).